Unforgiving shackles

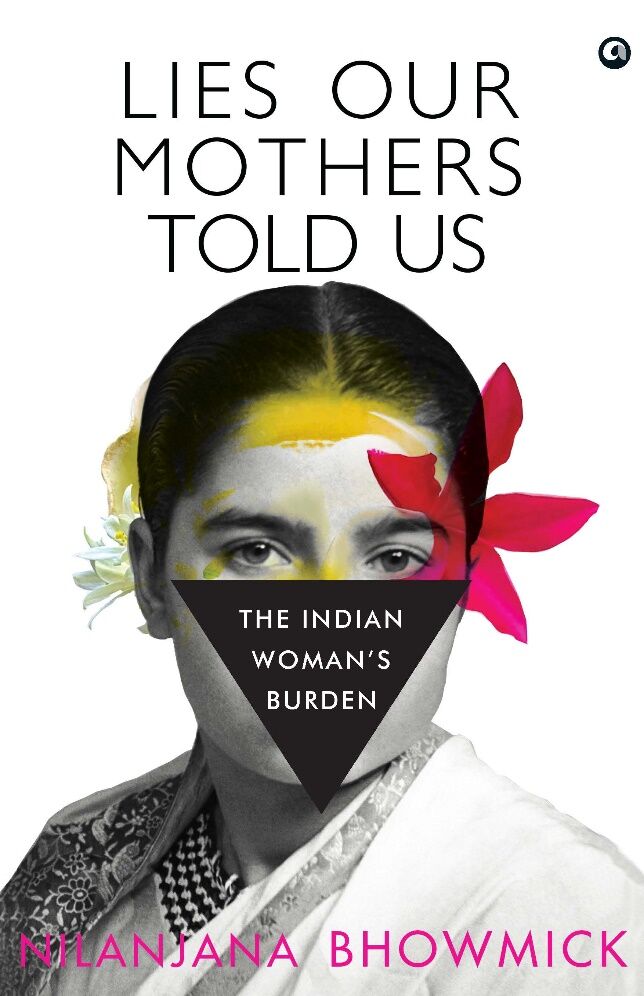

Through the book, Lies Our Mothers Told Us, acclaimed journalist Nilanjana Bhowmick carries forward the legacy of pioneering feminist writers — despite whose efforts the 21st-century ‘superwoman’ remains enchained in the cage of ‘double-shift’ chores. Excerpts:

Feminism is the radical notion that women are human beings.

—Marie Meiselman Shear

In early 2019, I had gone to register my car papers at the motor vehicles office in Noida. As I stood waiting for a man to photocopy my documents, I became aware of the stares of people around me. This was, of course, nothing I was not used to, but these stares were slightly different, more uncomfortable, more in my face. I looked up and looked around slowly—all I could see were men, men, and more men. On that courtyard of easily a few hundred men, I was the only woman, or at least the only one unaccompanied by a man. I took a picture of the courtyard and when I looked at it later, I was amazed. We often talk about women missing from our public spaces but to see it captured was a different feeling all together.

Often, when I am in a car driven by a female friend, male drivers honk, try to corner the car—for them it's a sport, to see us flustered and scared, to push us back into our homes. Ask any woman who drives, especially in North India, she will have a similar story to tell. I have never wandered through the streets like I often see men doing. My relationship with the streets is strictly functional, as I believe is the case with most other women. We try to go from point A to point B, getting our work done without grabbing too much attention.

***

In early February in 2018, in a small room in Madanpur Khadar, a resettlement colony in the Indian capital, a group of young girls were discussing their participation in a year-long project by the nonprofit organization Jagori called Aana-Jaana (Comings and Goings) with a study group from abroad. As part of the project, the girls had recorded their daily struggles of negotiating a hostile public space on a closed WhatsApp group.

'Sheher (city) where no one listens to you', an entry read; a freestyle hip-hop song with over 40,000 views on YouTube followed the entry. That morning, they performed it for the study group.

'Girls in this city have a tough life…but you cannot scare us away any more,' sang the diminutive Khadar ki Ladkiyan (Girls of Khadar), in their knock-off jeans and long synthetic tops. Their anger was quiet but palpable.

'More power to you sister,' they spat out as they punched and slashed the air, swaying to the beats of finger snaps and knuckle raps.

But staking a claim to the city in real time has not been easy.

A Save the Children report in 2018 on safety in public spaces for Indian girls found that one in three adolescent girls was scared of traversing the narrow by-lanes of their localities, as well as the road to go to school or the local market. Nearly three in five girls reported feeling unsafe in overcrowded public spaces. Over one in every four adolescent girls perceived the threat of being physically assaulted, including getting raped, while venturing into public spaces, while one in three expected to be inappropriately touched or even stalked.

'Khadar ki Ladkiyan' was part of a wider project titled 'Gendering the Smart City' funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK, and headed by Ayona Datta, a professor of Human Geography at University College London. The project aimed to understand how women used technology and how that technology impacted the ways in which they negotiated their homes and cities on a daily basis. The participants were from Madanpur Khadar, a resettlement colony in Delhi. Jagori, a feminist NGO in Delhi, and Safetipin, a well-known ICT social enterprise, partnered with Datta on this project.

Datta describes the Khadar girls as 'urban millennials, who are living the paradox of India's digital revolution in an urban age…. They are avid users of the mobile phone, and active on social media through which they create solidarities, friendships, and support networks… within these paradoxes they emerge as young, millennial, gendered citizens straddling the "new" and "old" India, eager to speak, but held back.' Their song, she continues, 'brings to light the opportunities and challenges of navigating the city as these women leave home to pursue paid work and education, and are simultaneously constrained by the boundaries of traditional gender roles.'

A very important aspect of the everyday lives of the Khadar girls is violence—not just sexual, but also structural. In their song the girls reiterate that the state knows 'we need better roads, they know we need public transport. They know we need water and toilets. They know we need safe streets. It's not a lack of knowledge that is the problem, rather a lack of attention.'

'The song was really about using technology and not necessarily in the way that the smart city expects you to…. Like, you know, clicking on Facebook likes and Twitter likes and doing the surveys circulated by the government, but using technology in a way to draw attention and mobilize and advocate about continuing intergenerational problems around lack of infrastructure, gender-based violence, and so on,' Datta told me in 2020.

The impact of the song had left Datta amazed. 'We had not even thought of shooting a video initially but the idea came from the girls,' Datta remembered.

The girls had kept it a secret from their parents during the shoot, for the fear that they would not be allowed to take part in the project because dancing and singing were not considered appropriate. However, after the video went live, to everyone's surprise, many parents sent it to their extended families back home.

'It made us feel free—we were able to put into words the anger we feel at the fear we feel in a city where we were born,' said Ritu, one of the Khadar girls. 'Why do we have to run back home after school or work? Why can't we hang out like the boys or men do in public squares?'

Because when the public space is hostile, we have no choice but to accept this misogynistic definition of a woman's rightful place in society.

In 2012, a young student, Jyoti Singh, was raped inside a moving bus by six men and then thrown on the streets to die. Her parents had migrated to New Delhi from a small village in Uttar Pradesh in search of a better life for their children. Her father worked as a loader at the Delhi airport and sold his ancestral land to fund her education. The tragedy that befell her brought focus to the struggles of this new generation of underprivileged girls and women, empowered by education, having to step out to work to substantiate the family income. Her gruesome rape and murder had underlined the imminent need for making public spaces safer for women. Singh was the same age as the Khadar girls when she was murdered and came from a similar socio-economic background.

'When we talk about safety, we are not just talking about violence. It is to remove fear,' Kalpana Vishwanath, a sociologist and urban safety and gender rights activist said in an address to the International Association of Women in Radio and Television in September 2015. Citing the example of Delhi, she had added that 'there is a huge amount of fear, probably higher than the actual expression of violence. And our effort is to remove that fear.'

Vishwanath, co-founder and CEO of Safetipin, a social enterprise that uses data and technology to build safer, more inclusive smart cities, held that safety was not just the experience of violence, it's the fear of violence that makes women more dependent on men for protection, or makes them restrict their mobility. She had also rightly pointed out that when women are perceived as victims, the narrative then becomes that of protection rather than rights. 'And we are saying safety is a right, without fear of violence.'

'Cities are not well planned; they are not gender inclusive. We have to ask whether we are planning cities for gender inclusion? Are we planning more transport facilities? Are the places well-lit? We need to address a lot of stakeholders, not only the police. We need to talk to urban planners, municipality, and local governments to build safer cities,' she said. 'Instead of a top-down model where city planners decide. We should build cities that local people want, women want. A safe city, where one can live without fear.'

Urban planning in our cities continues to disregard gender as a factor precisely because of this idea that women must be protected and so, surveilled. According to Ayona Datta, who researches the politics of urban transformations in the global south, smart cities, in our current scenario, would merely result in increased surveillance.

'We know that surveillance can actually be highly unequal and highly debilitating for women because the first violence they face is from their families, from their kinship networks, from the neighbourhoods, from the neighbours. And this surveillance can be loaded with cultural perceptions about women's rightful place and women's rightful body, the attire and behaviour and demeanour,' Datta told me in an interview.

In 2017, the Indian government approved a budget of `98,000 crore to turn eight major cities, including Delhi, perhaps one of the most unsafe cities for women in India, into smart cities. But, as Datta says, the concept of smart cities as a policy is based on a corporate and technologically driven understanding of cities. Through her Gendering the Smart City project, Datta wanted to explore what such a concept could mean for women and what stakes they have in this sort of technology.

'Gendering the Smart City is a critique of smart city that has been conceptualized and driven from a very top-down policy through use of digital kinds of technologies, particularly making use of big data and real-time analytics, to efficiently manage and govern cities. And then to think, how can women use technology to support their everyday struggles or to, you know, circumvent different kinds of challenges in everyday life, whether it's about violence, whether it's about livelihoods, and so on and so forth.'

In our country, the way men and women look at safety is very different. Policy makers, who are largely men, approach safety from the perspective of protecting women, rather than as a basic human right that needs to be guaranteed. The smart cities project comes from a belief that technology is the solution to all sorts of social problems. But technology cannot resolve discriminations that are internalized and embedded in our daily lives. 'If you read some of the reports by PricewaterhouseCoopers and Cisco, which are some of the main players in the smart cities sector globally, they generally treat smart safety as a question of surveillance by increasing CCTV cameras [and] by increasing police presence. Also, smart cities are a business model. So, the moment it becomes a question of surveillance, then you can sell CCTV cameras, then you can sell records and algorithms for command-and-control centres from where you can observe the streets and so on. But it doesn't really resolve the issue of patriarchy or misogynist patriarchy.'

(Excerpted with permission from Nilanjana Bhowmick's Lies Our Mothers Told Us; published by Aleph Book Company)