Tales with a tragic touch

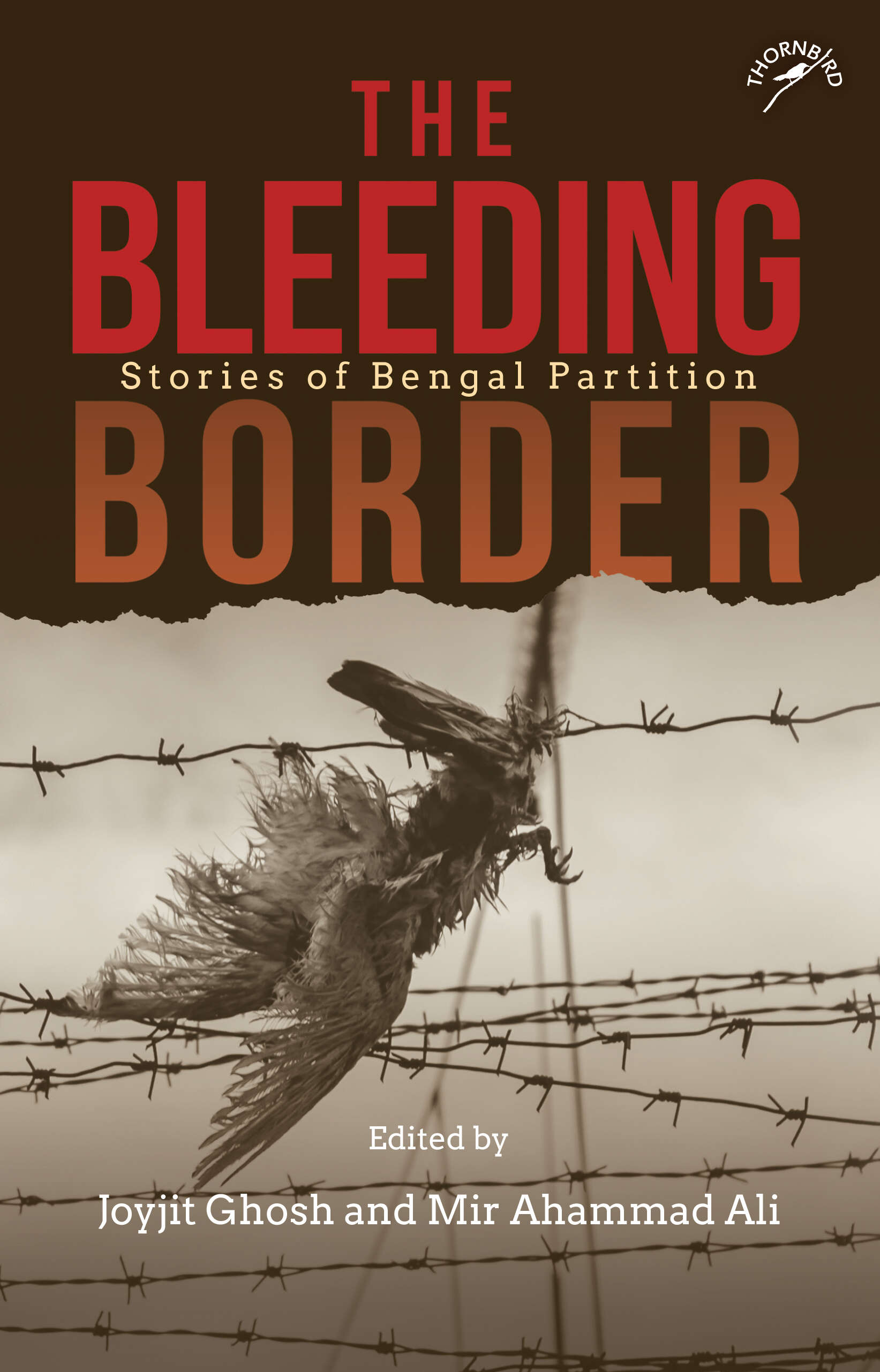

The Bleeding Border — edited by Joyjit Ghosh & Mir Ahammad Ali — is a rare anthology of 24 poignantly-written Bengal Partition stories by both celebrated and lesser-known authors. Excerpts:

Dear Ma, I—your ill-fated daughter, disgrace to your esteemed caste–religion–family—am writing you from a distant land. When my heart twists in pain, when my deep[1]stored prejudices mislead me constantly like a whirlpool of a labyrinth, when I can no longer find a solution to the sum of my life crafted by many hands, then, dear Ma, just then your face like that of a Durga idol flashes before my eyes. To whom but you should I confide in the chronicle of my disgrace, of my dishonour, of my twenty-two-year-old life burnt up by the epoch-ending fire of history! You're my Ma,—no caste, no religion, no pride of family, you're only my Ma; you're not the scripture-versed daughter of Vedantabagis, nor the wife of Samkhya-Smrititirtha, you're my Ma, this is your true identity; you held me once in the depth of your being, I'm a companion of that tree-self of yours; whom shall I share with a slice of the endless pain of my battered, bloody heart, except you…

The town in East Bengal where once I, sprouted from the seed of my devoutly religious father, was interwoven with this living world with a fine thread of unity, where my childhood, adolescence and budding youth were spent, where I came to know humans, flowers, plants, rivers, sky, creepers, shrubs, forests, where I trembled in the immense wonder of the vivid and delightful mystery of my becoming—there, in that very town, the lord of the earth etched the badge of misfortune on my forehead. I cannot forget that night. Even at the slightest recapitulation of that event, I still turn blue in fear—

From the afternoon it was gradually becoming clear that something would happen. And yet till noon everything seemed normal. The school was closed after a couple of periods, though we couldn't guess anything. The headmistress called us in her chamber and said to us, 'Don't loiter around and engage in any adda anywhere. Go home straight away. Remember, you have your qualifying test ahead. Don't go by the road through the market. You don't listen to me at all.' Coming out of her chamber, we all laughed covertly. We knew that Rabeya di had an unreasonable fear about the road through the market. As a matter of fact, the permanent address of the adda of the college students and the loitering young men at Bakultala crossing was then a spot of common dislike for all the guardians in the town, including Rabeya di. We knew that they daringly discussed politics, literature, sports and girls at the highest pitch of their voice, even occasionally fought too; seeing us they would become loquacious. We didn't particularly dislike them: they elicited a response from the deepest recesses of our being.

We went by that very road through the market. As soon as we reached Bakultala crossing, Poppy whispered to me, 'C.H.'—'C.H.' stood for Chandan. Chandan, Firoj, Maqbul and Anowar stood under the bakul tree. They all glanced at us for once and the next moment became engrossed among themselves. They appeared to be somewhat subdued and distracted. We thought they perhaps had a fight with someone. We knew very well that if Chandan and Firoj were together, any mishap might take place. As we walked along, we kept on gossiping on these. Poppy suddenly said, 'Why is Runa's heart a little heavy? My elder brother probably didn't look at her!' Firoj was Poppy's elder brother. Runa said in a ringing tone, 'Mind your own business. You needn't bother about me…

I reached home with quite a light heart. But seeing me you were about to break into tears, Ma, and said, 'Oh! You're back!' As if you assumed that I wouldn't come back at all. I was amazed and said, 'What do you mean!' Then you couldn't withhold tears, your voice almost choked in terror, and you said, 'O, a disaster has fallen! The Bhattarcharyas of Kendua were all hacked to death last night. They'll attack this town tonight.' It took some time to sink in, then I grasped you. You slowly drew my head on your lap and said, 'Don't be afraid, my child. Why are you afraid? We are with you, aren't we?' Back in our childhood, when we would be afraid, you would often hearten us this very way. Then with anxiety in your voice, you said, 'Those two have gone out so early in the morning; there's no news of them at all since then. As if they need to lead in all affairs! And I've to face all misfortune!' The 'two' referred to Chandan and Dada—my elder brother. I felt I couldn't possibly disclose to you, Ma, that I've seen Chandan with Firoj and his pals. You quite often repeated, 'I've to bear all the burden of danger for this boy from another family. His parents have sent him here to study, and only God knows how he's doing in the college. The fellow has grown wings after setting foot in the town. I won't be able to take the responsibility of this boy. Let everything pass peacefully, then I'll…

The rumour spreading from mouth to mouth since the afternoon was gradually turning into a news. The nameless, shapeless clouds of horror were slowly coalescing under the clear sky of autumn. They were trickling together one by one in the big mosque. Chandan and my Dada used to go out frequently, they couldn't sit down quietly; their faces were gradually growing pale, the sheer sense of conviction was gradually melting down drop by drop through the chink of their closed fists—there was hoping against hope. Towards the onset of the evening, they took a round for the last time. I remained lying in my own room. They spoke with you in a hushed tone for a while in the big hall. Once Chandan came into my room, sat down by the cot, took up my palm and said, 'Don't be afraid Bula, I'm standing by you, can't you trust me?' Chandan, with his strong build, appeared like a hero from the myth: I sank my face into his arms. He was caressing my hair, his hot breath was falling on my neck, at the tip of my ears, on my tresses; my terror was gradually taking the shape of an untasted intense joy—my face was cupped inside his two hands, the fragrance of Chandan pervaded my whole body and the consciousness inside it. Chandan! Ah Chandan! Chandan was trembling, I was trembling, and the darkness in the four corners was also trembling…

'Chandan, Chandan, Shankar'—

No noise from outside then reached my ear distinctly. It seemed that someone from afar, and with much worry, called Chandan and my Dada. Chandan went out, stricken with fear, as if he knew that the call would come; all of you, including my Dada, were then on the courtyard. Perhaps you wanted to restrain them, Ma, for you said in a tone of warning, 'No one must open the front door.' Perhaps Chandan said, 'Aunti, Firoj is calling.' You said, 'Nobody I trust anymore.' Without paying heed to you, they opened the door and went out. The tinkling music of the ankle[1]bells of my heart had finally stopped, the shadow of fear surreptitiously thickened there—why weren't they coming back, Chandan and Dada, oh God, why weren't they? Chandan Chandan… Sinking my face in the pillow I said to myself, 'They may have murdered Chandan', the lizard didn't say 'tick tick'; I said to myself, 'Chandan is alive', the lizard didn't say 'tick tick' this time either. It seemed that the sound of opening the door vibrated the air-waves ages and ages ago. The fear inside was terrorising me; many different pictures of fear in their complex geometric shapes in the roomful of darkness kept staring at me without blinking, like the eyes of a bodiless female ghoul…

(Excerpted with permission from Joyjit Ghosh & Mir Ahammad Ali's 'The Bleeding Border'; published by Niyogi Books)