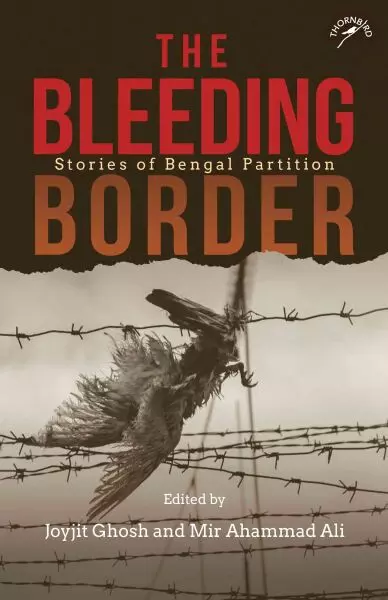

Stained with blood, soaked in agonies

Depicting gruesome violence, tension and anxiety at the ‘porous and fragile’ Bengal border during the Partition, this anthology — edited by Joyjit Ghosh and Mir Ahammad Ali — of 24 short stories written by oft-forgotten writers of West Bengal and Bangladesh makes for a disturbing read. Excerpts:

It was a thinking day. We were reading Sujata Bhatt, our eternal favourite, and enjoying the magic of her poetry where the real and the surreal often marvelously blend. All on a sudden, her poem titled ‘Partition’ drew our notice. We read the poem time and again, particularly its concluding lines, ‘How could they/have let a man/who knew nothing/ about geography/divide a country?’. The question continued to haunt us, and we believe, it haunts many like us even today, after more than seventy years of the Partition. The irony is, the ‘man’—Cyril Radcliffe—whose fateful line of demarcation divided the Indian territory into a ‘Hindu’ India and a ‘Muslim’ Pakistan, had never before been to India, nor had he the necessary skills for drawing a decisive border. But it was he who emerged as the destiny in the history of Partition that involved gruesome sectarian violence, persecution of minorities and wide-scale migration whose legacies (unfortunately) are visible even to this day. People coming from socio-economically disadvantaged background in particular had to face the heterogeneous forms of atrocities that included arson, murder, child abuse, rape, pillage and uprooting. The history of Partition, in fact, is not only huge but immensely complicated as well. But there is no scope to dwell on this history at this point. Our prime objective here is to explore how the partition narratives deal with the discontents of Bengal Partition and represent the trauma of countless masses who lost their homes and became rootless when the Bengal borderland was created with suddenness.

The Bengal border, to borrow a poignant expression from Bashabi Frazer’s poem ‘This Border’, indeed ‘cuts like a knife/Through the waters of our life’, and it bleeds still. Its wounds are hidden in the nerve cells of those victims who are alive, and its pain is often transferred from one generation to another—gradually establishing a redefined map. The Partition in 1947, therefore, is not an isolated incident. It surpasses a fixed temporal frame and speaks of a conscious present that continues to plague people on both sides of the border.

It is often said that Bengal Partition in comparison with that on the western border of India has not received much literary attention. Some even go to the extent of saying that celebrated Bengali writers more or less remained ‘silent’ regarding this cataclysmic issue. Thus, ‘Partition Literature’ has become almost synonymous with the writings of Saadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, Bhisham Sahni, Ismat Chughtai, Intizar Hussain, Joginder Paul and others, and we often tend to ignore the contribution of the authors from the eastern and north-eastern parts of the country and Bangladesh.

This obviously speaks of a politics in the formation of canon particularly when it is evident that Bengal Partition fiction is no less powerful and appealing than its western counterpart. One may think of short stories and novels by the authors like Jyotirmoyee Devi, Pratibha Basu, Ramesh Chandra Sen, Satinath Bhaduri, Manik Bandyopadhyay, Narendranath Mitra, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Atin Bandyopadhyay, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, Prafulla Roy, Debesh Ray, Sadhan Chattopadhyay, Amar Mitra, among others, from this side of Bengal, and Syed Waliuallah, Hasan Azizul Huq, Rizia Rahman, Selina Hossain, Akhteruzzaman Elias from that side, which is Bangladesh. The list of authors of Bengal Partition literature is not only huge in its corpus but immensely relevant in the socio-political context of the present day.

The stories of the present anthology include some of the most striking and dominant themes of the Bengal Partition and its aftermath. One major theme is obviously the ceaseless movement of rootless masses in search of safe shelter in an ambience of generalised violence. Dinesh Chandra Ray’s ‘The Guardian Deity’ depicts the journey of refugees (on the road, through the forests and even crossing the river) in the direction of Hindustan when communal riots began. The protagonist of the story thus narrates her own experience: ‘There was a journey of three days and three nights ahead of me… There were robbers at the street-corners hiding in darkness. Yet I was taking myself forward safely; there was some sort of a valour in it.’ The experience of the narrator is therefore represented in a positive light because once she is on her way, she is free from her past which was almost synonymous to the strict rules imposed on her by her father-in-law in the name of the service of the deity. But this kind of depiction of a journey is very rare in partition stories. Border-crossing is almost always portrayed as a terribly painful and wearisome experience in these narratives. One may remember the agonised experience of Rajab Ali, the central character of Devi Prasad Sinha’s ‘Border’: ‘…that is the border. So impossibly long, impenetrable has become this little path—as if someone is pulling a piece of rubber continuously from both the ends—no matter how much he runs, the path goes for eternity.’ This represents ‘the territorial and human consequences of a border’, to echo the words of William Van Schendel.

Thus, the Bengal border, as depicted in partition stories, is often huge as well as ‘impossibly long’. But there is an ironic dimension to the border as well: the border is porous and fragile—fragile like the body of Fazila in Sohrab Hossain’s ‘Between the Borders’, who knows that women like her have to yield now and

then to the ugly desires of professional touts or the BSF, or the BDR: ‘They had come to accept these professional hazards for the sake of livelihood, and to keep base life afloat for their children. They knew that it was necessary to extend such favours if their bundles were to cross borders.’ A woman’s body at the border is therefore cheap like her knapsacks.

In their Introduction to The Trauma and the Triumph: Gender and Partition in Eastern India, Jashodhara Bagchi and Subhoranjan Dasgupta observe that in both the divided states of Punjab and Bengal, ‘women (minors included) were targeted as the prime object of persecution. Along with the loss of home, native land and dear ones, the women, in particular, were subjected to defilement (rape) before death, or defilement and abandonment, or defilement and compulsion that followed to raise a new home with a new man belonging to the oppressor-community.’ This statement is based on historical truth. Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (2000) and Joya Chatterje’s The Spoils of Partition: Bengal and India 1947–1967 (2007) bear testimony to it. Regarding the fictional representation of the ‘spoils of partition’ we would like to refer to two stories: Hasan Azizul Huq’s ‘The Exile’ and Ahana Biswas’s ‘A Mother Divided’. In the first story, the portrayal of violence is gruesome. The reader may remember that section of the narrative where Bashir wildly runs to rescue his near and dear ones from the clutches of the criminals but to no avail:

The house has already been gutted to nothingness. They are gone. Bashir’s seven-year-old son, pierced and stuck to the earth by a spear and the body of a twenty-six-year-old woman, looking like a black, burnt piece of wood, were there in the ruined gutted house. The air was heavy with the foul smell of raw flesh burning.

(Excerpted with permission from Joyjit Ghosh and Mir Ahammad Ali’s ‘Bleeding Border’; published by Niyogi Books)