Pioneers of Modern India: The rebel who ignited dreams

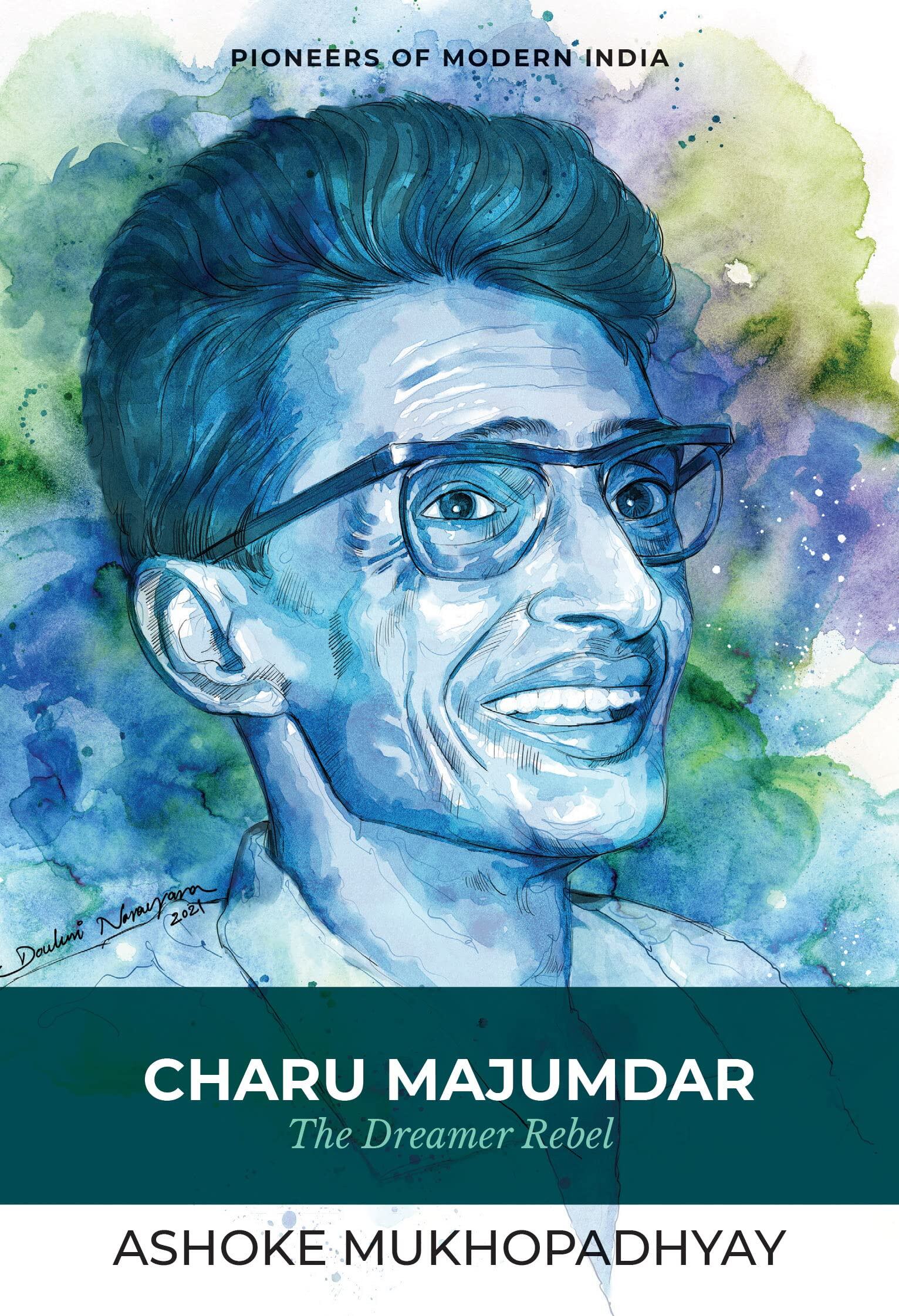

In the meticulously researched monograph, ‘Charu Majumdar’, Ashoke Mukhopadhyay documents the life of India's legendary rebel who inspired deprived masses to revolt against suppression and sowed in them a dream of getting their very own republic. Excerpts:

In the end of 1963, disaffected elements within the CPI were busy with theoretical discourse on revisionism, charging S.A. Dange, the Chairman of CPI, for sinking the party to right opportunism. Charu Majumdar made it clear to his followers in North Bengal, 'The real fight against revisionism can never begin unless the peasant starts it through revolutionary practice.' He stressed the need to take revolutionary politics among the peasantry and 'take in hand the task of building a revolutionary party.'

Amidst a high-decibel anti-Chinese propaganda, Charu Majumdar did not change his pro-Chinese and pro-revolution stand just to win over the middleclass voters. On the contrary, he campaigned for revolutionary politics and consequently, he was defeated in the election. Yet, he garnered 3500 ballots in his favour!

At a time when the contradiction between antirevisionist and pro-Dangeite stands was getting sharpened, the draft party programme of the CPI for its forthcoming congress was circulated amongst the comrades. To discuss the programme, a meeting of the District Committee was held at the house of Ratanlal Brahman in Darjeeling. The next morning, while walking up the steep main road, Charu suffered a heart attack. Kanu Sanyal, Biren Bose and others brought him back to his Mahananda Para home. The doctor advised complete rest for weeks.

Besides occasional angina pain, Charu did not feel much difference, but the doctor recommended a consultation with a specialist. Neither the district nor the provincial committee of the CPI showed any concern for his treatment. However, at the initiative of a local comrade, a local cultural organisation, Katha O Kalam, arranged for a charity show for Majumdar and gave some money for the treatment. Members of another renowned cultural organisation in Siliguri, with whom Majumdar was attached, also extended monetary support according to their capacity.

Due to his heart ailments, Charu could not attend any of the party conferences. Then the split had happened. In November 1964, Indian Communists witnessed two party-congresses—leftists holding one in Calcutta, and the rightists holding a parallel one in Bombay. The former organised themselves into a separate party which came to be known as CPI (Marxist) while the latter retained the old name CPI.

The CPI (M) leaders promised to make it a revolutionary party, different from the 'revisionist' CPI, but in reality the new party leadership refrained from spelling out their exact views on China, the Sino–Soviet ideological dispute, the role of non-aligned countries, the future of the national liberation movements and violent or non-violent forms of transition to socialism. Radicals in the CPI (M) were highly disappointed.

Charu, who buried himself in political books during his recuperation break, realised the new party would also drift away from revolutionary politics. At the same time, he observed that it was significant that CPI (M) had emerged out of a stand against revisionism. It would release supressed initiatives in the revolutionary rank and file. He tried to crystallise his thoughts and started writing political essays, which would later be known as 'Eight Documents' of Charu Majumdar.

From the beginning of 1965, the Congress government started arresting communists, especially those who were under the CPI (M) umbrella, across the country. Charu was not arrested in the first batch primarily due to his absence in the party conferences.

Written on 28 January 1965, in his first document (Our Tasks in the Present Situation), Charu Majumdar analysed the reason of the large-scale arrests across the country, and stated:

This offensive against democracy has begun because of the internal and international crisis of capitalism. The Indian government has gradually become the chief political partner in the expansion of American imperialism's hegemony of the world. The main aim of American imperialism is to establish India as the chief reactionary base in South-East Asia.

This crisis, according to Charu, would be deepened. People's discontent would be translated into bigger struggles and

The Communist Party therefore will have to take the responsibility of leading the people's revolutionary struggles in the coming era, and we shall be able to carry out the responsibility successfully only when we are able to build up the party organization as a revolutionary organization.

Majumdar also presented a scaffolding of the proposed revolutionary organisation—

Every party member must form at least one Activist Group of five. He will educate the cadres of this Activist Group in political education; every party member must see to it that no one from this group is exposed to the police; there should be an underground place for meetings of every Activist Group. If necessary, shelters for keeping one or two underground will have to be arranged; a place should be arranged for hiding secret documents; every Activist Group must have a definite person for contacts; a member of the Activist Group should be made a member of the Party as soon as he becomes an expert in political education and work. After he becomes a Party member, the Activist Group must not have any contact with him. This organizational style should be firmly adhered to. This organization itself will take up the responsibility of revolutionary organization in the future.

As the basis of the Indian Revolution was in the agrarian movement, the main slogan of the political propaganda campaign, according to Majumdar, would be to highlight those factors which ensured a 'successful agrarian revolution'.

Over eight months beginning from 28 January to September 1965, Charu Majumdar exposed his core political thoughts through the second to the fifth document. Unfortunately, before completion of the fifth document, Majumdar was arrested.

In the second document titled, Make the People's Democratic Revolution Successful by Fighting against Revisionism, Majumdar spelt out the types of revisionist thinking:

The first among revisionist thoughts is to regard 'Krishak Sabha' (peasants' organization) and trade unions as the only Party activity. Party comrades often confuse the work of peasants' organization and trade union with the political work of the Party...it should be remembered...that the trade union and the peasants' organization are one of the many weapons for serving our purpose.

…the true Marxists know that carrying out the Party's political responsibility means that the final aim of all propaganda, all movements and all organizations of the Party is to establish firmly the political power of the proletariat. It should be remembered always that if the words 'Seizure of Political Power' are left out, the Party no longer remains a revolutionary Party

Following an analysis of the Tebhaga movement, Majumdar held that the party needed to establish its leadership on mass organisations, however, 'It should be remembered that in the coming era of struggles, the masses will have to be educated through the illegal machinery….

What is the Source of the Spontaneous Revolutionary Outburst in India? Charu Majumdar's third article, written on 9 April 1965, identified the post-war liberation movements across the globe as the fountainhead of inspiration. The toiling mass found that no imperialist force could destroy the red flag of hope fluttering in Peking. Majumdar raised a call—

Yes, Comrades, today we have to speak out courageously in a bold voice before the people that it is the area-wise seizure of power that is our path. We have to make the bourgeoisie tremble by striking hardest at its weakest spots. We have to speak out before the people in a bold voice—see, how poor, backward China, within a span of sixteen years, has, with the help of the socialist structure, made its economy strong and solid. On the other hand, we have to expose this treacherous government which has, within seventeen years, turned India into a playground of imperialist exploitation. It has converted the entire Indian people into a nation of beggars to the foreigners.

The third document clearly expressed Majumdar's preference of China's socialistic structure to others.

Meanwhile, as senior comrades of the Darjeeling committee including Kanu Sanyal were behind the bars, Charu recruited a band of new young comrades—two of them students—for applying his theories in the first document into practice. The team was sent to Kadam Mullick at Buraganj in the Naxalbari region to set up five-member activist groups. They could easily form a number of activist groups. Charu advised them—'Make the peasantry dream that they are going to get their republic; the land will be theirs, it will be their own government, but they have to fight, and they may not live to see the end'.

Charu managed to send his first three documents to Kanu Sanyal and other members of Darjeeling District Committee in the jail.

The fourth document—Carry on the Struggle against Modern Revisionism—pointed out some characteristics of revisionism including Soviet leaders' support to Indian ruling class, narrow nationalism, the ploy to protect the exploitation by monopoly capital. Majumdar suggested some ways to fight the revisionism:

It should be remembered that no movement of the peasants on basic demands will follow a peaceful path. For a class analysis of the peasant organization and to establish the leadership of the poor and landless peasants, the peasantry should be told in clear terms that no fundamental problem of theirs can be solved with the help of any law of this reactionary government. But this does not mean that we shall not take advantage of any legal movement. The work of open peasant associations will mainly be to organize movements for gaining legal benefits and for legal changes. So among the peasant masses the most urgent and the main task of the party will be to form party groups and explain the programme of the agrarian revolution and the tactics of area-wise seizure of power. Through this programme, the poor and landless peasants will be established in the leadership of the peasant movement... The programme of active resistance has become an absolute necessity before any mass movement. Without this programme, to organize any mass movement today means to plunge the masses in despondency...

Majumdar also stressed the need of preservation of cadres.

…proper shelters and communication system are necessary. Secondly, teaching the common people the techniques of resistance, like lying down in the face of firings, or taking the help of some strong barrier, forming barricades... Thirdly, efforts to avenge every attack with the help of groups of active cadres...even if a little success is gained in one case, extensive propaganda will create new enthusiasm among the masses.

In this document, Charu Majumdar also outlined his views on the secret party organisation.

The fifth document—What Possibility the Year 1965 Is Indicating?—was a logical extension of Majumdar's first and the fourth documents. He called for armed resistance against the government attack—

...in the interest of mass movements, the call should be given to the working class, the fighting peasantry and every fighting people to (1) take to arms; (2) form armed units for confrontation; (3) politically educate every armed unit. Not to give this call means pushing without any consideration the unarmed masses to death.

(Excerpted with permission from Ashoke Mukhopadhyay's 'Charu Majumdar'; published by Niyogi Books)