Pioneer of the ‘parallel’ cinema

From the Pioneers of Modern India Series, this biography by Arjun Sengupta makes a deep dive into Shyam Benegal’s cinematic journey—from his early influences and advertising career to his landmark films and television contributions. Excerpts:

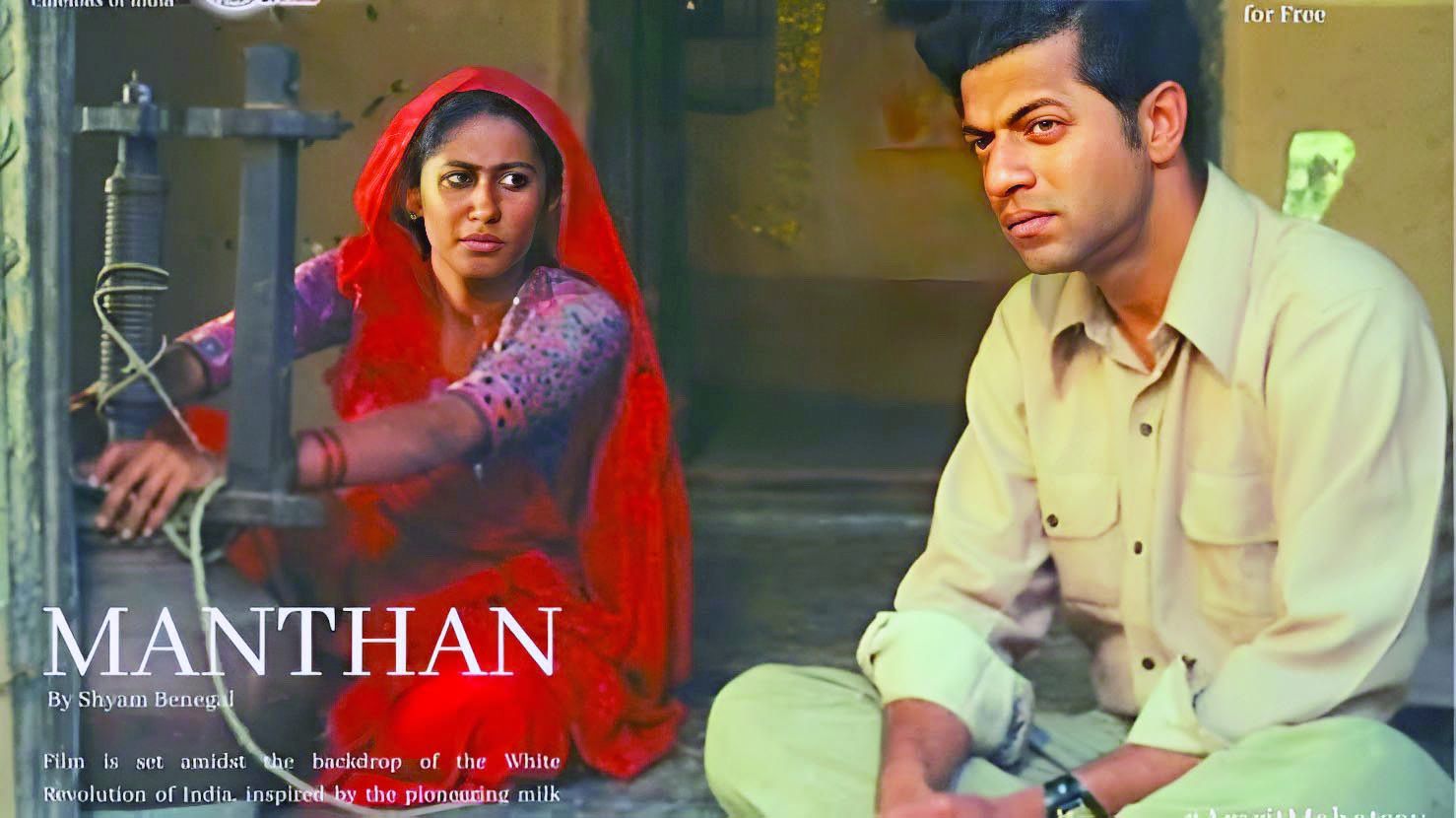

Benegal’s first three films are powerful statements made with integrity, emphasis and authority. The idealism of his youth, his intellectual growth, his zealous hatred of oppression, unfairness, and inequality burst forth in stories seething with anger, frustration, and the hope of a more equitable future. They are stories from the heartland, set not in escapist spaces conjured up by Bollywood that don’t really exist anywhere, but in places that are authentic and real. Benegal shot these films on location, taking with him the entire cast and crew for the duration of the shoot. In each of these films, old hands and absolute newcomers bonded together as a team, deeply aware of the importance of what they were doing. These films were set in villages and small towns, and like the light in a magic lantern, laid bare the deep-rooted patterns of life that had been around for centuries. His perspective was that of an educated man for whom Independence was an opportunity to not just be free of colonial shackles but also chains of superstition, ignorance, and divisions and exploitation based on caste and position within the social framework. At heart, Benegal believed in the vision of Nehru and in these films he depicted a pivotal moment in history where the old and new are struggling to attain a new equilibrium. It’s not an accident that one of his titles is Manthan, a visual analogue of a time in turmoil destined to throw up a new order. For him, this order had to be defined by secularism, egalitarianism, and equal opportunity. Through accident or design, these films established him as a film-maker whose subject went beyond the regional. As an artist, his subjects excelled in showcasing both the unrivalled diversity of the country as well as the deeper rhythms and systems of thought that united them all.

Ankur (The Seedling)

Ankur marks a watershed moment in Indian cinema. Apart from its virtues as a film, it represents one of Benegal’s chief attributes as a film-maker—his refusal to compromise. He refused to play it safe because it was his first film and include elements from the popular cinema of the time. He had learnt from Satyajit Ray that it was possible to make a film on one’s own terms, and he never veered away from this conviction. It is almost obstinately different and deliberately stays away from any kind of compromise. The importance of the film also goes beyond the tenacity of one man’s persistence. All kinds of factors intersected to make it happen and even ensure that it had an audience.

The story of Ankur had been with him since his college days. It was based on real events, and a lot of the political idealism of his college days is present in the story. The peasants’ movement of 1971–72 that followed a failed harvest provided immediate relevance to the story. He developed a script from his story but it took him 14 years to find a producer. He looked for financing, but the kind of film he wanted to make seemed a very risky venture at the time. Who would want to watch a film with newcomers that had no song and dance routines, and which told the story of feudal oppression in the countryside? As it turned out, there was an audience waiting eagerly for it. Ankur was successful at the box office. Benegal took his crew to actual locations, depended on ambient light, natural sound and folk music. All through his career he used local traditional musical forms and styles to great effect. It not only lent authenticity to his films but also reflected the vast diversity of India’s cultural history. In a way, his films have been a response to the singular idea of India that is propagated by commercial films made in Mumbai. He has opposed this singularity with multiplicity. There were enough people who embraced this new and fresh attitude, because of which he has had a dedicated audience for most of his career.

There were other factors that helped the film. While there had been a tradition of realistic films in Indian cinema, it was only in the 1970s that the Indian Government started actively taking steps to support and subsidize films that would have a broad educational and cultural impact. This was part of a continuing process after Independence to forge a pan-Indian identity that would celebrate its diversity within the context of a single, unified nation. Nehru had established the blueprint for it by trying to mould India into a socialist and secular country. In the early 1970s the government limited the number of imports from Hollywood, and set up institutes to train and subsidize young film-makers. Fewer films from Hollywood meant that there was more space for films made in India. Encouragement from the government meant a lot for young, enthusiastic film-makers like Benegal. While, in the long run, one may question the efficacy of these policies, state intervention at this crucial moment played a major role in the development of what came to be known as ‘parallel’ cinema. Its patronage was dependent on the subject matter and its treatment, but it also emphasized a more realistic approach beyond the rubric set up by commercial cinema.

Benegal used this freedom and opportunity to take an incisive look at Indian rural society by setting his first film in a typical village in Andhra Pradesh. In spite of its particularity, the setting is illustrative of a wider context. It represented how structures of power and oppression operated all across India. If Ankur seems like a remarkably mature and self-assured first work, it’s because of decades of training and preparation that preceded it. He had honed his craft as far as the practical business of making films is concerned during his time making advertisement films. His determination to be a director from a young age ensured a single-minded dedication, and he built upon what he had learnt all through his childhood and youth to develop an intellectually sound and inherently humane philosophy. Benegal is ultimately a humanistic film-maker. His films have a strong intellectual, left-leaning philosophy but his approach to his stories is driven by compassion. This rescues his films from being dry sociological tracts and make them more about the travails of oppression, the pathos of suffering, and the worth of simple human dignity and courage in adverse circumstances.

However, when it came to financing, Ankur would probably have never been made if not for Benegal’s connections in the advertising industry. Ankur was produced by Blaze Films, a company that distributed advertising films all over the country. Blaze Films contributed to Ankur’s success and had an impact in two unexpected ways. They convinced Benegal to make it in Dakhni, and not in Telugu. Dakhni had connections to Hindi, which automatically meant a wider reach. Secondly, their network of distribution ensured that the film was watched in places it would never have reached if it were financed by one of the traditional production houses. Everything, it seemed, conspired to give the film the best chance it deserved.

(Excerpted with permission from Arjun Sengupta’s ‘Shyam Benegal’; published by Niyogi Books)