Nuggets of aesthetic brilliance

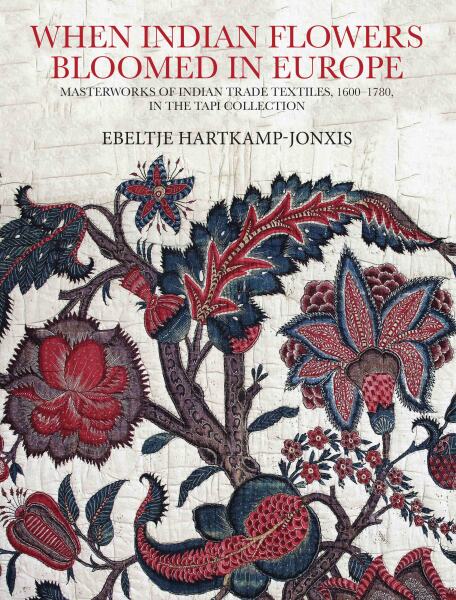

When Indian Flowers Bloomed in Europe is an informative text, accompanied with rare images, relating to 30 textile masterpieces from TAPI Collection, which represent the aesthetic height achieved by Indian artists in the 17th and 18th centuries. Excerpts:

Chintzes

For various reasons chintzes were popular in Europe right from their first imports. Their permanent colours and washability were most welcome characteristics because hardly any European fabric of the time had these qualities. Only undyed fabrics with a strong fibre, such as linen, could be regularly washed without changing the structure of the fabric. Woollen fabrics became coarse after regular cleaning, and since chintzes were lightweight fabrics, they were more comfortable to wear than traditional woollen garments. Moreover, the price of patterned chintzes compared favourably with that of European block-printed fabrics. Chintzes with elaborate, bright-coloured designs were even less expensive than European worsted fabrics with brocaded designs—in fact, they were actually cheap in comparison with European silks with colourful patterns.

In the 18th century, chintzes democratized the consumer market in northern Europe, as the upcoming middle class could afford to buy low-priced chintzes with simple, floral motifs. For the clothing of the more well-to-do, chintzes with more intricate patterns were available. Chintzes remained popular in Europe until the late 18th century, after which European machine-woven cottons with block-printed, plate-printed and roller-printed designs replaced handwoven and dyepainted Indian chintzes.

Most chintzes that have been preserved through the centuries, particularly those of the finest quality, are attributed to production centres along the Coromandel Coast. Pulicat (Paliacatta) was the VOC's headquarters from 1610 until 1690. Thereafter Negapatam (Nagapattinam), further south, was the seat of the VOC's governor of the Coromandel Coast. In 1781, troops of the English East India Company conquered Negapatam. From 1649, Madras (Chennai) was the EIC's headquarters. At the creation of the Madras Presidency in 1785, the city became the capital of this administrative subdivision of British India, which included most of southern India.

The competition between the two companies was fierce. Although the EIC was hampered by import restrictions imposed in the home country to protect the English textile industry, it secured its trade in Indian chintzes by exporting them, right after their arrival in London, to countries on the continent, including the Dutch Republic. The much smaller Dutch textile industry was not able to organize similar impediments for the VOC. Hence a large number of chintzes have been preserved in Dutch collections.

Both the English and Dutch companies had chintzes made mostly with small floral repeat patterns, to be used for the tailoring of clothes. Large chintz panels for use as wall hangings, table cloths and bed furnishings were mostly ordered and traded by private entrepreneurs. These large chintz panels are known in the English-speaking world as palampores, after the Hindi term palangposh, meaning bedspread.

Among the dye-painted palampores, those with a flowering tree were most favoured in Europe. Like other large chintz panels with different motifs, they probably served mostly as bedroom furnishings. No rooms with their original, en suite furnishings with this design are extant, but individual palampores with a flowering tree are preserved in fairly large numbers (Fig. 3.1; see also Cat. nos 4, 6, 8 and 9).

The trees that are rendered on palampores have sinuous trunks. The origins of the motif of the flowering tree, which were rendered on palampores produced for European customers from circa 1700 onwards, are complex. Looking for visual sources in the Islamic world, John Irwin drew the attention to trees on some 15th- and 16th-century Persian album leaves, observing that the outlines of these trees are similar to those on some early Coromandel palampores. The design also resembles the rendering of trees carved in relief on a number of marble footstones of Muslim graves in the vicinity of Pasai, in north Sumatra, Indonesia (Fig. 3.2). These footstones, dating from the first half of the 15th century, were produced in Cambay (present day Khambhat), the principal harbour city in Gujarat, from where they were shipped to Pasai. The flowering trees, with sinuous trunks, seen on the perforated marble screen windows of the Sidi Sayeed Mosque at Ahmedabad, constructed in the 16th century, are also similar.

Few 17th-century dye-painted tent hangings from the Deccan with a design of a flowering tree are preserved. The trees on these textiles do not have sinuous trunks, but the flowers on their branches are related to those seen on early dye-painted palampores with a flowering tree made for the European market. Lastly, the designs of tree-trunks and flowers appearing on two—presumably Deccani—embroideries, which are part of a large set of tent panels dating from the late 17th century, bear striking similarity with those seen on early 18th-century palampores (Fig. 3.3). It is, however, almost impossible to establish whether the flowering trees on 15th- and 16th-century Persian miniature paintings, on 15th- and 16th-century Indian stone carvings and on 17th-century textiles made for local patrons were seminal for the ones on dye-painted palampores destined for the European market. Designs on 17th-century European, particularly English, embroideries (Fig. 3.4), also influenced the representation of the flowering tree on early palampores.

The flowering tree on chintzes varies from a rather robust, sinuous tree with large flowers, standing on a mound formed by lumps of small rocks or pyramidal scales, to a more slender one with angular twists and small flowers, standing on a Chinese-looking hillock. Similar slender, sinuous trees standing on hillocks are rendered in a repeat pattern on wallpaper made in China for the European market from the 1750s until the late 18th century. This design was probably adapted by European draughtsmen for palampores with such Chinese or pseudo-Chinese design.

In Europe, the flowering tree on palampores had no symbolic meaning, but the Indian middlemen and painters who were involved in the making of cotton paintings with a flowering tree probably associated the tree with the kalpataru or wish-fulfilling tree, which is deeply embedded in Indian thought. The flowering tree can also be associated with the Tree of Life, a fundamental concept in many religions and philosophical traditions.

In the corners of a number of palampores with a flowering tree, there are vases with large bouquets (see Fig. 3.1). These are after late 16th- and 17th-century European flower engravings. The engravings that were sent over to the Coromandel Coast were reprints. New impressions of the original engravings continued to be made far into the 18th century.

Large chintzes with a symmetrical design of pointed palmettes must have been popular in Europe as well, judging from the fair number of palampores and quilted bedspreads with this design that are extant, most dating from the 1730s until the 1740s (fig. 3.5). Ottoman and Safavid fabrics with a repeat pattern of palmettes were imported both in India and in Europe, where these designs were imitated and emulated. Palmettes were also incorporated in Persian and Indian carpets. However, carpets with a symmetrical arrangement of pointed palmettes, whether Persian or Indian, are unknown. The symmetrical design of pointed palmettes was probably created on the drawing board of a European draughtsman.

A number of palampores with motifs copied from Japanese visual sources are also preserved (Fig. 3.6; see also Cat. no. 16). Woodblock prints or fabrics from Japan must have been available for the designers of these palampores.

Although Chinese influences are quite common on palampores, figurative Chinese images were seldom copied. A rare example of this is a picture of a Chinese dignitary, attending a performance of a female dancer who is accompanied by musicians, rendered on two similar palampores (Fig. 3.7). Was it an early 17th-century Suzhou woodblock print, depicting a moment of relaxation of a Chinese emperor, or one showing the emperor Ming Huang reflecting on his beloved Yang Guifei, as described in the tragic Tang love story, that served as an example? Their romance inspired many musicians, writers and artists over the centuries. Alternatively, was the image based on a design on so-called Coromandel lacquer screens, Chinese folding screens made for the export to Europe, or on similar images on Kangxi porcelain?

The design on chintzes made by the yard are usually adaptations of those on European textiles, among which were silk fabrics. Some designs on European textiles were fashionable for only a few decades. Others were long-lasting patterns, such as the ones consisting of small flowers. Motifs on so-called bizarre silks—silk fabrics with 'strange,' asymmetrical designs—produced in Europe from the mid-1690s until the 1720s—are also present on a number of chintzes (Fig. 3.8; see also Cat. no. 21). Although bizarre silks are a European creation, some of them show eastern influences. Among the names of a few designers that have come down to us is Alexander Senegat, who worked in Amsterdam as textile designer between 1701 and 1719. Seven of his engravings with fanciful, asymmetrical, floral designs have been preserved, all dated 1719. An advertisement in the Amsterdamsche Courant of 6 September 1718 makes Senegat particularly interesting to us. It announces the publication of a collection of his designs 'for the use of many different fabrics'. Among those that find mention, are 'geschilderde doeken' (painted cloths). These two words most probably stand for Indian chintzes.

In the 1730s, silks with symmetrical flower arrangements enlivened by the inclusion of lacy, ribbon-like motifs, became fashionable in Europe. Silks with this design, nowadays known as lace-patterned silks, were called persiennes in France at the time of their production, as their designs were supposed to be reminiscent of oriental art forms. It is no surprise that chintzes were ordered in India as a substitute for these attractive and fashionable, but expensive European silks (Fig. 3.9; see also Cat. no. 21).

In the last quarter of the 18th century, textiles with dainty patterns on a light ground, such as ones with scrolling flower stems, became popular. Block-printed and copper-printed cottons with such designs were produced in Europe, mainly in France and England. Most likely it was the English East India Company that had these copied in India, as the Dutch trade in chintzes was dwindling by that time (Fig. 3.10).

The change in demand from pseudo-oriental motifs to purely European ones was the writing on the wall for Indian chintzes. But the fate of Indian chintzes was actually sealed by technological developments and new discoveries in chemical processes in Europe. Roller-printing, also called cylinder-printing, which made it possible to print cottons at a high speed ended the once-firm position of Indian chintzes in the European textile market. In 1783, Thomas Bell had this printing method patented in Scotland. By 1810, as roller-printing became increasingly used, chintzes were no more competitive with European roller-printed cottons in terms of the price/quality ratio. Earlier, Robert ('Parsley') Peel (1723–1795) and Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf (1738–1815) had established very successful printing works, respectively in the village of Church, Lancashire, and in Jouy-en-Josas, near Paris, where initially wooden blocks and steel plates were used for the printing of cottons. It is significant that in the course of the 18th century the term 'chintz' was used both for Indian dye-painted and printed cotton fabrics as well as for cotton fabrics printed in Europe.

(Excerpted with permission from Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis' When Indian Flowers Bloomed in Europe; published by Niyogi Books)