Mosaic of vivid encounters

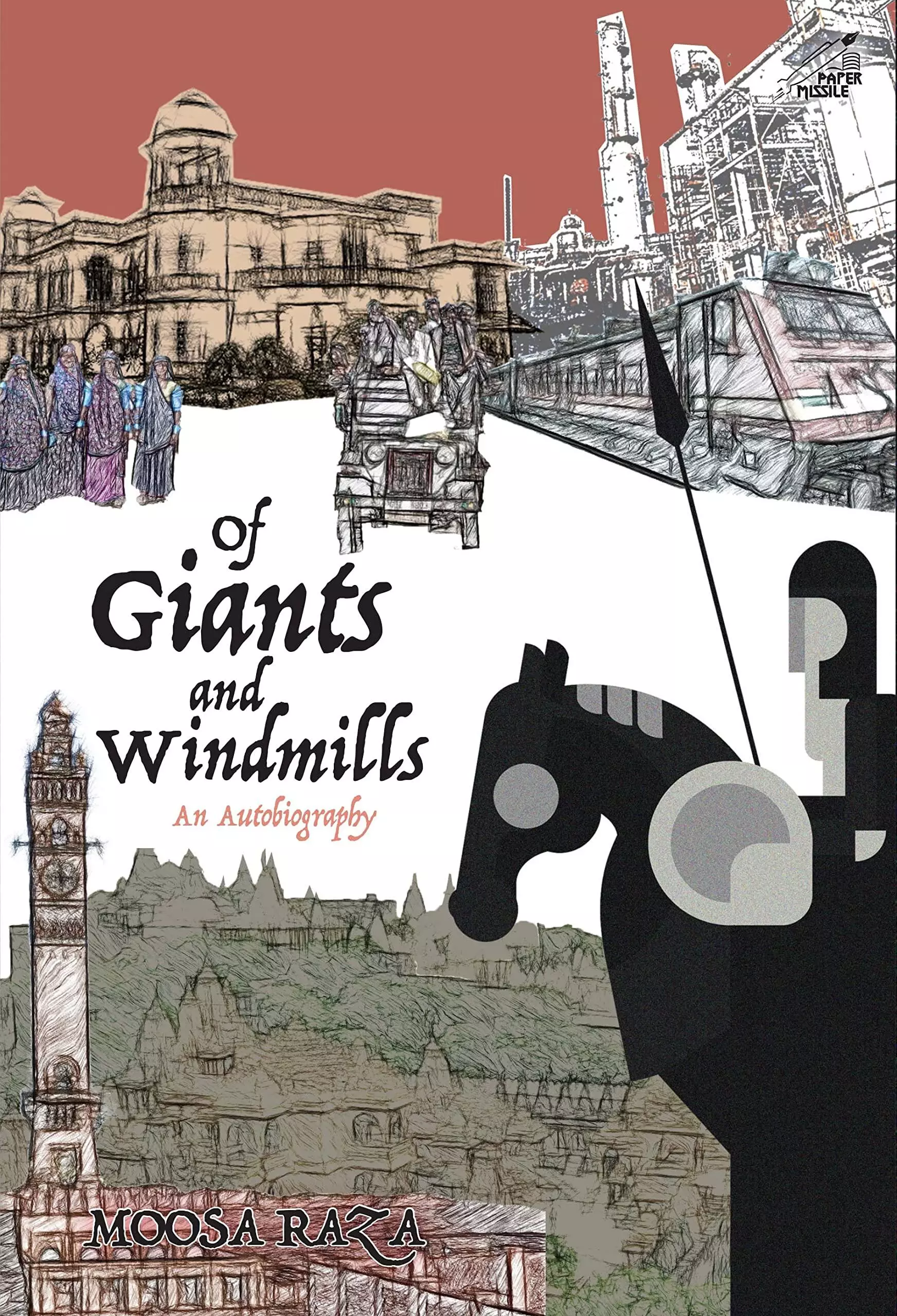

Of Giants and Windmills is an autobiographical account of Moosa Raza — an IAS officer of the 1960 cadre — who, with utmost honesty and wit, shares his encounters with maharajas, politicians, tribals, tigers and others during his extensively diverse stints in the civil services. Excerpts:

Historians claim that an edifice called the Babri Masjid was erected in Ayodhya by a general of Babur, the Mughal conqueror of India, in 1528. It is also claimed by some historians that the general Mir Baqi erected the ‘mosque’ on the orders of Babur. Reportedly, there is an inscription testifying to this claim. Babur had just won the battle in Panipat and had to conquer and occupy Delhi. He had to subdue the opposing Afghan nobles, the defeated army commanders of Ibrahim Lodi, who had dispersed over Delhi and its environment.

However, the actual history around the Babri Masjid is shrouded in the mists of history, clouded by legends, old people’s tales, motivated comments of European travellers and hagiographic histories written mostly by Muslim court historians, praising Babur and his dynasty as great upholders of Islam, demolishers of temples, destroyers of deities worshipped by Hindus and so on.

I had no opportunity to see the Babri Masjid before it was demolished. I only saw it on TV when the destroyers, perched on its old weatherbeaten domes, were chipping away at the bricks and mortars. I visited Ayodhya on the evening of the 8 December, 1992, more than twenty-four hours after the demolition and after the makeshift Ram temple had been erected on the rubble of the mosque. I only saw the listless security force officials standing idly by as though waiting for another catastrophe to happen. I learnt later that more than seventy companies of the state police had been posted to Faizabad—a classic case of safeguarding the stables after the horses had fled.

On the morning of 6 December, 1992, however, I sat before the TV in Delhi watching the unruly, milling crowds, with their saffron headbands and robes, gathering in the open ground before the Babri Masjid. Though the meeting was taking place under the sun, the volunteers, the karsevaks, had come well prepared to brave the weather. The top leaders of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement were already in Ayodhya. The commentator on the TV was waxing eloquent about the anticipated arrival of L.K. Advani, Murli Manohar Joshi, Uma Bharti, Kalyan Singh, Rithambra Devi and others at the site. Even Atal Bihari Vajpayee was expected to ‘grace the dais’ and address the large mass gathering of karsevaks who had gathered from all parts of India, fired with religious zeal.

That day, I wondered how Kalyan Singh, the BJP CM of Uttar Pradesh who had given a solemn undertaking to the Supreme Court of India that the mosque would not be demolished, was planning to keep these karsevaks in check. When I noticed the karsevaks on top of the first dome of the mosque, with their pick-axes, mattocks and large steel chisels, digging away at the dome as though their lives depended on bringing down the dome, I knew that a new chapter was being written in the history of India.

I was still hoping that the central government would intervene at this blatant breach of the Supreme Court orders. I should have known that court orders and solemn undertakings given even to the highest court in the land are meant to be broken with impunity. After all, the very Supreme Court, which tried Kalyan Singh for defying the court orders after giving a solemn assurance, punished him with a mere token punishment of one day in jail (till the sitting of the court) and a trifling fine of ₹20,000. Such is the punishment for a defiance that led to the demolition of a mosque and thousands of deaths in subsequent riots.

So, as I watched, nothing happened to prevent the demolition. The second dome was under attack. It would take the whole day for all the three domes to fall, along with their supporting walls and pillars. Though the mosque was close to 500 years old, made of mere brick and mortar, weather-beaten, never maintained or protected against the heavy rains, squalls and Sarayu floods, its plaster and paint already peeled off, it still resisted the combined destructive might of hundreds of karsevaks with all their chisels, mattocks and pick-axes. Muqabila toh dile natawaan ne khoob kiya (The frail heart still gave a tough fight).

Earlier in 1988, the late Mr Shahabuddin, former MP and firebrand political leader, attempting to safeguard the interests of the Muslims of India, had occasion to call on me when I was chief secretary of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. A mob, agitating for adequate power supply and control of meat prices, was attempting to set fire to a critically important bridge over the river Jhelum in Srinagar. When persuasion, tear gas and lathicharge by the state police failed to stop their advance, the police opened fire. There were some casualties. The national press had highlighted the incident. Mr Shahabuddin had come to Srinagar perhaps at the invitation of the locals to get a first-hand account of the so-called ‘high-handed’ behaviour of the police. And considerable criticism was aimed at the state administration for having ‘mishandled’ the mob.

I had known Mr Shahabuddin, a former Indian Foreign Service officer and a diplomat who had represented India abroad several times. Being a fair-minded man, he was satisfied when he heard our explanation. Thereafter, the conversation veered towards the conflict between Hindus and Muslims over the status of the Babri Masjid. Mr Shahabuddin was then the leading light in that conflict in the late eighties. As a student of the geopolitical trends in the country, the zeal and organisational capabilities of the Hindutva forces and the consequences of the march of psycho-history, I was apprehensive of the impact on the minds of the Hindus and the status of Muslims of India as a whole, if the conflict led to a more widespread involvement of the larger Hindu community of India. I was apprehensive that the agitation would only lead to strengthening the radicals and the defeat of secular forces.

‘What kind of compromise do you have in mind?’ he asked.

‘After all, the ruined mosque has not been in use for several decades. It is already being used as a temple. There is hardly any Muslim population in the vicinity that uses it even for Friday prayers. Part of the premises has already been in use as a temple. Would it not be advisable to let the Hindus have it, in exchange for withdrawing all claims on all other mosques in India? There are more than thirty mosques in Ayodhya. You could ask for their support to pass suitable legislations to be incorporated as a part of the Constitution to safeguard status quo of all mosques as on 15 August, 1947,’ I suggested.

‘The RSS is not ready for any compromise on those lines. The moment you talk of surrendering Babri Masjid, they immediately follow up with a demand for Varanasi and Mathura. Their other affiliates, like Vishwa Hindu Parishad [VHP] and akharas, talk of other mosques in the rest of India.’

At that time, I had no idea that the Babri Masjid was being used as an emotional symbol of the Hindutva ideology. Any compromise on removing Babri Masjid from the national narrative would remove a powerful

As I watched the demolition on TV, little did I anticipate that I would be landing into the maelstrom the very next day. In the aftermath of the demolition, the Kalyan Singh government was dismissed and President’s Rule imposed in the state of Uttar Pradesh. At that time, Satya Narayan Reddy from Andhra Pradesh was the governor of the state. Two senior IAS

officers, Ashok Chandra and B.K. Goswami, were immediately despatched to Lucknow to take over as advisors to the governor. Before they were in place, under the shadow of the President’s Rule and under the governor’s direct control of the director general of police, a makeshift temple had already come up on the debris of the mosque without any hindrance. A situation was allowed to be created where through an illegal fait accompli, the Hindus could claim possession, being nine points of law.

On the evening of 7 December, a day later, I was ordered to proceed to Lucknow and take over as the third advisor to the governor. Obviously, since rioting had already started in Uttar Pradesh and other parts of India, and most of the victims happened to be Muslims, the government thought a Muslim advisor in place would divert criticism from the government of acting in a partisan manner. I was supposed to represent the secular face of the central government.

(Excerpted with permission from Moosa Raza’s ‘Of Giants and Windmills’; published by Niyogi Books)