Indo-Saracenic buildings: confluence of architectural styles

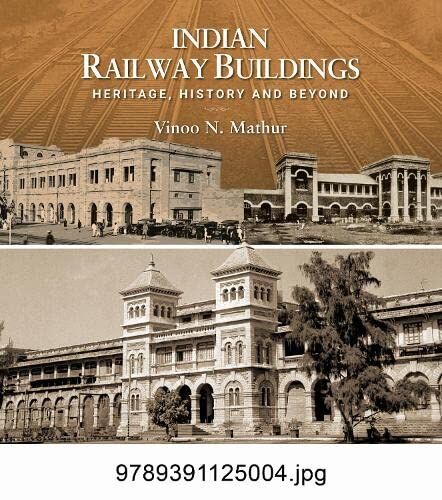

Vinoo N Mathur, through his well-researched book, ‘Indian Railway Buildings’, takes readers into the fascinating world of colonial railway architecture in India. Excerpts:

The Indian subcontinent had well-developed styles of architecture, as illustrated in Hindu temples, palaces and cenotaphs, as well as Islamic architecture in its mosques, fortresses, palaces and tombs. Both schools evolved over time, the essence of which was catalogued in the writings of James Fergusson in his History of Indian and Eastern Architecture. As the ruling colonial power, the British exerted authority through their various institutions, such as courts, municipal corporations, railways, post offices, educational establishments, administrative offices, the military forces and so on. Therefore, public buildings had to be constructed on a monumental scale, to improve visibility and create a sense of awe among the subject population.

The design of public buildings became of greater importance after 1858, when Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India. Until then, the architectural style used was based on what was happening in Britain. As a result, classical revival, Romanesque and gothic revival styles or a combination of them with vernacular elements were adopted in various parts of the country. However, the focus was to use architecture as a means of legitimising the Empire.

The issue, as to whether an effort to adopt indigenous architectural styles should be considered, was a subject for discussion for several years. There were conflicting views; some felt that, as the colonial objective was to impose European systems of justice, law and order and therefore, buildings should reflect European styles and provide a distinctive symbol to the locals to respect and admire. The contrarian point of view, espoused by architect William Emerson, was that a more appropriate policy would be to adapt indigenous styles to current needs as had been done, very effectively, by Muslim rulers of India in the past. As a result of this discussion, several architects began to experiment by incorporating elements of Indian and Indo-Islamic architecture. Thus was born the Indo-Saracenic style, which was a blend of Indo-Islamic and Hindu temple architectural elements with Indo-gothic and neoclassical features. A wide range of buildings were constructed in the style, including courts, clock towers, railway stations, schools and colleges, hospitals, public halls, art galleries and palaces.

The main proponents of the style were the architects Robert Fellowes Chisholm, Henry Irwin, Charles Mant, William Emerson, George Wittet, Swinton Jacob and Vincent Esch. Some of the important Indo-Saracenic buildings in India include the University Senate House, Madras (Robert Fellowes Chisholm, 1869–74); Mayo College, Ajmer (Charles Mant, 1875–85); Law Courts, Madras (J.W. Brassington and Henry Irwin, 1888–92); Muir College, Allahabad (William Emerson, 1873); Napier Museum, Trivandrum (Robert Fellowes Chisholm, 1872); Laxmi Vilas Palace, Baroda (Charles Mant and R.F. Chisholm, 1878–90); Amba Vilas Palace, Mysore (Henry Irwin ,1900–12) and Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay (Charles Wittet, 1905). A large number of IndoSaracenic style buildings were built in Madras. The influence of the style may be observed in two of the finest British colonial buildings in India—the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta and the Rashtrapati Bhawan and Secretariat buildings in New Delhi. The architectural style spread outside India, for example, the Kuala Lumpur old railway station was designed as an Indo-Saracenic building by architect Arthur B. Hubback in 1910.

The characteristics of Indo-Saracenic architecture included onion-shaped bulbous domes, pointed and cusped arches, vaulted roofs, chajjas or extended eaves supported by brackets, minarets, domed chhatris (canopies), pierced open arcading, open pavilions, jharokas or harem windows and delicate stone openwork screens. The buildings often had central or corner domes. The bulbous domes had a drum along the bottom rim and a lotus motif and finial at the top. The roofline usually had conspicuous domed chhatri kiosks or pavilions of different sizes. The extended cornices were often all along the roofline and on all sides of the open pavilions. The openwork screens and jharokas were also conspicuous. The verandah arcades consisted of a pointed or cusped arch design with occasional use of the Moorish horseshoe arch. Some elements came from Islamic architecture such as the dome, pointed and cusped arches, while others came from Hindu architecture such as the chhatris, pillar designs and brackets. It was the architect's prerogative to mix and match features from different traditions, depending on what took his fancy. Although we often associate the style with monumental buildings, it was also adapted to smaller structures such as roadside station buildings.

Egmore Station

The South Indian Railway (SIR) operated the rail network south of Madras. It had its Head Offices at Trichinopoly (now Tiruchirappalli) and was formed by the amalgamation of the Great Southern of India Railway Company and the Carnatic Railway Company in 1874. The former had its origin in constructing the railway line from Negapatam (now Nagapattinam) to Trichinopoly between 1859 and 1862, whereas the latter began by building the track from Arakonam to Conjeevaram in 1865 and, later, linked it with Madras. The Pondicherry Railway Company also merged with the SIR in 1879. The SIR network steadily grew in size and was a metre-gauge system with a few early broadgauge lines in the area that were converted to metre gauge. Egmore was the Madras terminal of the South Indian Railway system. By the end of the nineteenth century, with the growth in traffic, capacity constraints had begun to be felt at the old terminal station at Egmore. It was, therefore, decided to rebuild the station and remodel the railway yard to cater to the emerging requirements of the time. By this time, the Indo-Saracenic style of architecture had gained prominence in Madras, as a result of the remarkable work done by Robert Fellowes Chisholm (1840–1915) and Henry Irwin (1841–1922). Irwin also became the consulting architect to the Madras Presidency. In Chennai, his major works in the Indo-Saracenic genre included the Madras High Court, Law College buildings and the Government Museum. Elsewhere, he was the architect for the Amba Vilas Palace in Mysore, the Viceregal Lodge in Shimla and the American College in Madurai.

Although the designs for the station were developed by Henry Irwin in 1902, in what was described as a Moghul style of architecture, it was the SIR Company architect, E.C.H. Bird, who delivered the project. Construction of the new building began in 1905 and the station was opened on April 11, 1908. The building has a number of noteworthy features, such as the corner towers and central dome with a rectangular base, the beautiful carved pilasters and brackets, based on South Indian temple designs, the prominent corbels all around, the use of contrasting brick, granite and local sandstone, the ground-floor balustrade, the decorative cusped arches with hood moulding on the first floor, the openwork stone railing along the verandah and the roof crenellations. Other significant characteristics are the small kiosks, the frieze on the central façade, depicting the SIR emblem, the conspicuous domes above the corner tower and the lotus motif and finials on the domes. The stylistic features borrowed, both, from the South Indian architectural tradition as well as other building styles created an appealing, exquisite and unique IndoSaracenic masterpiece.

The building inside was modern at the time with electric lights and fans fed from the Railway power house nearby. The ground floor housed the waiting, dining, refreshment rooms and booking halls, apart from station offices and a post office. The first floor had retiring rooms provided with a telephone connection to facilities at the station. The booking offices and waiting halls were exceptional with beautiful columns and arches, ornamental designs and superb woodwork of the booking windows. At the time, the operational area for trains had three sets of platforms with an iron work foot overbridge and a splendid three-span steel plate roof with glazed gable ends covering all the platforms. The station was the starting point of the famous Boat Mail to Dhanushkodi from where passengers would transfer to the ship that took them across the Palk Straits to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The station began handling electric traction in 1935 and has, more recently, been converted from metre to broad gauge. Over a century on, it still caters to the rail travel needs of the southern districts of Tamil Nadu, apart from local commuter traffic.

(Excerpted with permission from Vinoo N. Mathur's 'Indian Railway Buildings'; published by Niyogi Books)