India's delectable desserts

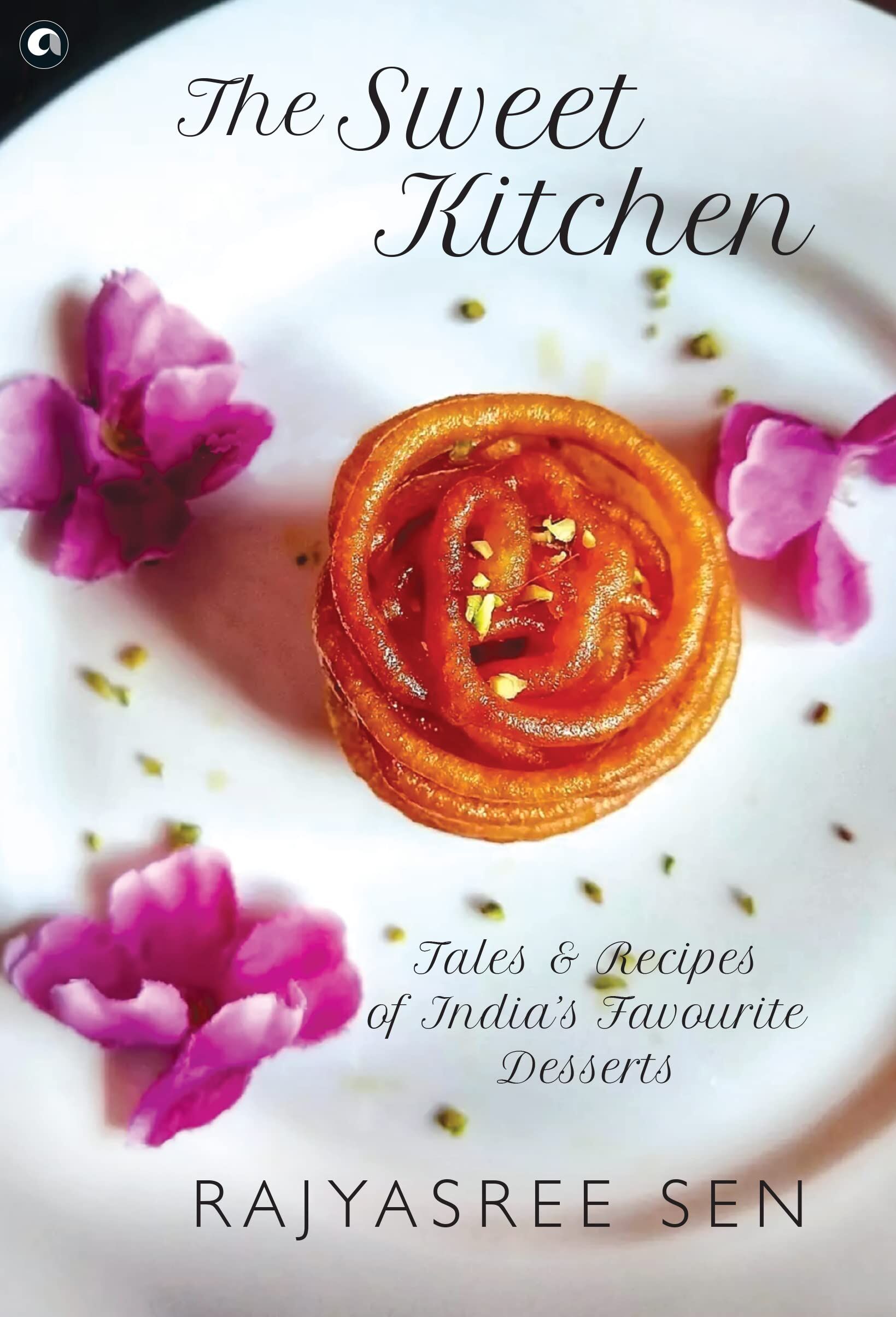

The Sweet Kitchen provides a ringside view into the history, origin and cultural influences of iconic sweet dishes — along with their recipes — that Indians have been relishing for ages. Excerpts:

Mishti khaabe?' is invariably the question with which a guest is welcomed to a Bengali household, even one outside of Bengal. This rhetorical question is usually followed by the arrival of a quarter plate with something salty—a nimki or a thin-crust Bengali samosa called shingara—and a selection of sweets which are, more often than not, different types of sandesh. A staple of Bengali cuisine, sandesh is a mouth-watering delicacy made from sweetened cottage cheese, sometimes in a delicious union with date palm jaggery. Sandesh is, however, much more than the sum of its ingredients—invented at the height of the Bengal Renaissance, it was a symbol of cultural refinement and haute cuisine at the time, and subsequently, a cure for every discerning Bengali's interminable craving for mishti in particular and for pre-siesta desserts in general.

No other state in India makes sandesh or any variant of this crumbly sweet. Nor has any other state ever laid claim to its creation. In fact, sandesh is so quintessentially Bengali that every ceremony and custom in Bengal includes some avatar of this delicacy. Often, as part of a bridal trousseau or totto, where it is customary to carry a fish dressed as a bride complete with saree and sindoor—here, the bride's family substitues the real McCoy with one made entirely of sandesh. This fish is made of chhanar sandesh, a sweetened cottage cheese, which is typically rolled into balls or flattened into small discs, and sometimes placed in moulds to resemble the shapes of fruit or shells similar to biscuit or tart moulds. This piscine sandesh, which can serve at least twenty to thirty people, is lovingly designed to resemble a real fish with its eyes, scales, and tail in their proper proportions.

The genius of the Bengali confectioners—both Hindu and Muslim—is most clearly visible in the impressive array of milk-based sweets that make up the repertoire of Bengali sweets. A defining element in most of these sweets—from the sandesh to the rosogolla and rosomalai—is that they are made partly or wholly from the sweetened cottage cheese we know as chhana. The use of chhana is unique to Bengal, but before the eighteenth century, even in Bengal, sweets were generally made from evaporated milk or kheer, as in most parts of India today. This erstwhile reluctance to use chhana can be traced back to the belief that 'cutting' milk with acid to make chhana is tantamount to sin.

Bengali sweets can be loosely divided into two categories: homemade sweets such as patishapta, naru, pithe, and payesh; and those that were created and perfected by Moiras in sweetshops, such as the chhana-based sweets, sandesh and rosogolla. It's important to understand the fine distinction between chhana and paneer. Chhana is the softer, crumblier version of paneer before the latter is pressed into its solid form. Popular folklore has it that sandesh was created by an enterprising milkman whose milk had curdled. Instead of throwing the milk away, he flavoured the solid part of the curdled milk with jaggery and divided the mixture into roundels. There is no way to check the veracity of this story, but it has been repeated often enough to make its way to the oral tradition that surrounds the mysterious origins and history of sandesh.

A more plausible story, however, concerns the early Portuguese settlers in Bengal, whose fondness for cottage cheese brought chhana to Bengali kitchens in the seventeenth century. Historically, the Portuguese were renowned confectioners, and their cheese and dessert making skills would have been an inspiration to Bengali confectioners. A large number of Portuguese men also married Bengali Muslim women—many of these women were accomplished cooks and confectioners themselves. The women, in turn, adopted Portuguese culinary practices which resulted in a new kind of sweetmeat making its appearance in the home via the kitchen or a local shop. In Sweet Invention: A History of Dessert, Michael Krondl mentions that the French physician and traveller François Bernier, who lived in India between 1659 and 1666, had observed that, 'Bengal likewise is celebrated for its sweetmeats, especially in places inhabited by the Portuguese, who are skillful in the art of preparing them and with whom they are an article of considerable trade.' There is no question that Portuguese cheese influenced desserts in Bengal and neighbouring Odisha.

Sandesh was probably created by confectioners and sold commercially during the second half of the nineteenth century. Till the mid-nineteenth century, there is no mention of a sandesh or rosogolla in recipe books or in literature. Although I have been told that the word 'sandesh' is mentioned in medieval Bengali literature, I have never been able to ascertain this. The word is also mentioned in Chaitanyacharitamrita, the biography of the fifteenth-century Bhakti saint Chaitanya, and in the fifteenth-century poet Krittibas Ojha's Ramayana, but whether the sandesh mentioned in these works is the same as the sandesh we eat today is unclear.

In Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal, it would not be an exaggeration to say that every street has a sweetshop and a chemist or two. The chemist usually keeps a stock of digestives that help fellow Bengalis survive until their next meal, after which the whole process starts again. The first sweetshops in Calcutta mushroomed in the nineteenth century, and Bengalis immediately flocked to them. Moiras, who were known for sandesh, often inspired family cooks who hoped to replicate the fashionable dessert at home—but trust me, this is one of those sweetmeats that never tastes as good when made at home.

Which is why, even today, sandesh, pantua, and mishti doi are rarely made at home. These were created and perfected by Moiras in sweetshops. My grandmother, who was a stellar cook, and even our family cooks, who whipped up the most delicious Bengali dishes, never wasted time making sandesh since you could always purchase the very best of sandesh at the neighbourhood mishtir dokaan.

Even today, you can see Moiras sitting in the small sweetshops, wearing just a lungi or a dhoti folded above their knees, bare chested, and with a prominent paunch (a work hazard), leaning over a big dekchi of oil, frying shingaras and jilipees, and wiping their brow with a checkered gamcha, which is usually draped over their shoulders.

In fact, the story of sandesh would not be complete without dwelling on the Moiras, the original creators of the sweet. As a testament to the all-consuming impact of sandesh and mishti on even the most evolved and intellectual of us, writer and musician Amit Chaudhuri's conceptual artworks, displayed as part of 'The Sweet Shop Owners of Calcutta and Other Ideas', provide a unique perspective on sweetshops in Renaissance-era Bengal. In it, Chaudhuri has photographed the proprietors of some of Calcutta's most famous sweetshops—dressed in their kochaano dhuti-panjabi with Kashmiri shawls draped over their shoulders. These men—skilled entrepreneurs and gourmands who set up famous shops such as KC Das and Ganguram's—nurtured Calcutta's love for mishti. These were also the men who hired the singularly talented cooks from the Moira community that eventually stirred up sweet-making traditions in Bengal.

The Moiras have also played a critical role in Bengal's cultural reformation. Once Calcutta was named the capital of British India in 1833, it attracted thousands of people from neighbouring states and districts—artisans, landowners, and entrepreneurs. The Moiras migrated from the surrounding districts, especially Hooghly, and were part of this influx of migrants into the newly-minted capital. As is the case in India, caste determines what you do and where you do it. The world of sweets is no different. The Moiras were one of the original nine castes which made up Bengal's Nabasakha caste group—a group of occupation-based castes. But the sweet tooth bit through the caste barrier. As a result, even at a time when caste determined many social and dietary exclusions, the Moira community's social standing was quite elevated.

Krondl narrates how Bengali Brahmins, who never accepted food as gifts because they didn't want to inadvertently touch food that a lower-caste person might have cooked, happily accepted sandesh. Because what is caste in the face of a delicious crumbly mouthful of sandesh? Another reason for the prominence of the Moira community in Bengal can be ascribed to the spread of Vaishnavism in Bengal in the pre-colonial era. The Vaishnavites worshipped Krishna who, as a pastoral god, received milk-based products as offerings. This was one of the reasons why the future of the Moiras was assured in Bengal. Separately, the Moiras were also patronized by the Bengali zamindars, who prized symbols of refinement such as the sandesh, and whose opulent lifestyles sometimes meant eating themselves to a standstill.

(Excerpted with permission from Rajyasree Sen's 'The Sweet Kitchen'; published by Aleph Book Company)