Candid reconstruction of a gory past

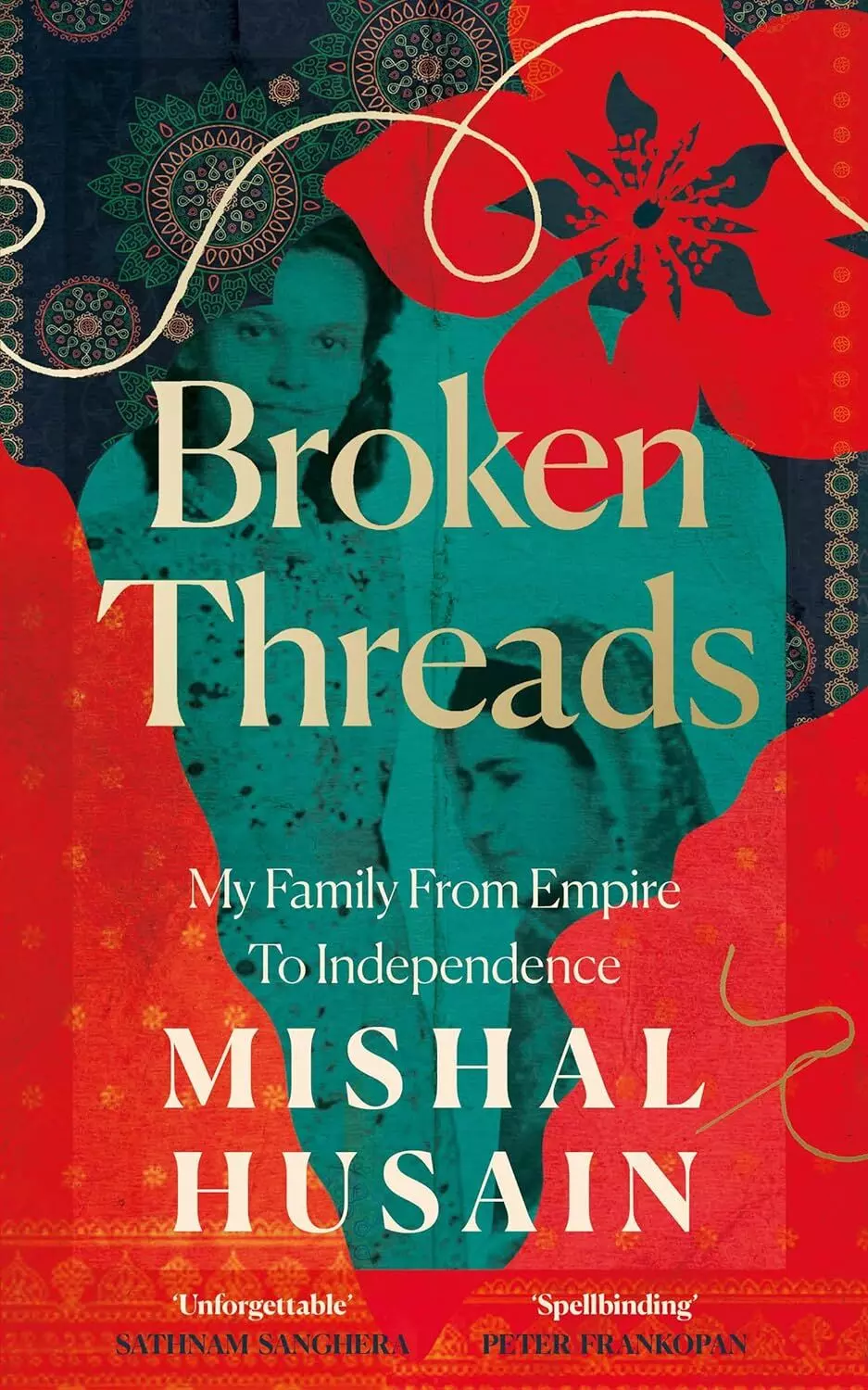

Told mostly through the lens of her ancestors, Mishal Husain’s Broken Threads assembles bits and pieces of information to weave a comprehensive history of British India, its independence, and the Partition

The past is often laden with a quintessential mystique and charm, irrespective of the nature of impact—good, bad or something that can’t be categorised—it had on the people who carry (or carried) its baggage. The degree of turbulence simmering in a particular era from the past defines the intensity of mystique associated with it. The tough times, in particular, nudge the ‘residents of past’ to document the bygone when they become ‘migrants to future’—almost with a sense of desperation to vent out the lava boiling in the inner recesses of the soul. Sorrow and despair, it is rightly said, are the most honest and poetic sources of artistic expression.

The grandparents of Mishal Husain—a BBC broadcaster and documentary maker who has her roots in present-day Pakistan (only if it can be said so)—lived through the most turbulent phase of India-Pakistan history: a couple of decades preceding and following the Independence, which was tainted with the blood flooding out of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs.

Her paternal grandfather, Mumtaz Husain, born in Multan in 1920, had penned down more than thirty years of his life before ending his memoir “abruptly, almost mid- sentence, around 1954”—largely due to ensuing events which “were more painful to recall.” A young boy from a conservative Muslim family—with Hindu origins—in Multan, Mumtaz would end up pursuing a medical career at King Edward Medical College in Lahore, where he would fall in love with Mary Quinn who trained as a nurse in the city. Mary herself was born to Francis Quinn, an Irish Catholic, and Mariamma, a Telugu woman, in Narsipatnam in South India. Mumtaz’s secret marriage with Mary would fracture his ties with his parents for a large part of his life. For the doctor who served during wars and conflicts, from Japanese invasion in Burma to the bloody Partition, his half-completed memoir was “a small tribute to a person (Mary) who stood by me (Mumtaz) through a turbulent life like a rock of stability and faith”. Back then, Mumtaz was conscious, as he wrote: “There must be an inner hope that it will be worthwhile for anyone who comes across it, has the time to spare and the desire to – at least – glance over it.”

Mumtaz was not alone. Born in the same year as him in Aligarh, Tahirah Butt—Mishal’s maternal grandmother—too had put on record the events surrounding her life in the form of audio tapes and writings. Educated at Lady Hardinge Medical college in Delhi, ahead-of-her-time Tahirah was married to Syed Shahid Hamid—nine years older to her. Following his death in 1993, Tahirah could recollect him saying: “Writing comes so much easier to you than it does to me. You owe it to your children, you owe it to your country, to write.” Shaid, educated at Aligarh Muslim University and Sandhurst, and commissioned into the Army in 1934, too, wrote a book which he called “procession of memories.”

After decades, their grand-daughter Mishal would take up the pen to join these ‘Broken Threads’ and present before us a nicely written book that would intertwine her family history with the later history of the Empire, the Independence (read with Partition), and beyond—only to offer a fresh perspective to the saga that has been told time and again, yet insufficiently. Traversing from one forlorn source of information to another, rummaging through dust-catching letters, drawing threads from forgotten audio tapes and historic broadcasts relating to her ancestors’ lives—all this must have been a tedious but fulfilling journey for Mishal. She tempts readers to be a part of this immersive endeavour of rebuilding the past, brick by brick.

Through her book, Mishal touches upon not just the hard topics of World Wars and much-talked about internal politics preceding Independence, but also draws tangent to oft-overlooked stories of: the Bengal Famine which “comes quietly” and claims innumerable lives; the Burma war; the establishment of Aligarh Muslim University; the overturning of Caliphs in Ottoman Turkey; British campaigns in North Africa and other parts of the world and much more. Mishal’s experience and knowledge as a journalist and documentary maker are clearly reflected in her work.

The almost 300-page paperback with yellow leaf and its quintessential fragrance is easy on hands and eyes. Given the expanse of the timeline, geography, and complexities it covers in its compact size, the book punches above its weight by telling an all-encompassing story with remarkable clarity and flow. Still, oceans can’t be captured in a cup. So, readers looking for depth and breakthrough information may be disappointed.

The book is, essentially, the history of British India’s transition from ‘Empire to Independence’ from the lens of Mishal’s ancestors. Of course, information from multiple sources are incorporated in the book, but the narrative of Shahid, Tahirah, and Mumtaz form the spine of the story. In such a case, needless to say, readers would weigh the agency of the protagonists who also weave the story. Shahid and Tahirah, particularly as the former progresses through his career, seem more disposed towards the Crown, or at least pin their hopes upon it. Shahid was a soldier of some calibre and character, and he, understandably, valued his loyalty to his source of power. He rose through the ranks in United India, serving eventually as private secretary to Commander-in-Chief Auchinleck—a less talked about figure whose role was undermined by the Crown and Mountbatten—and would later play a role in shaping Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence after Independence.

Shahid and Tahirah’s pure reverence towards Jinnah had to come at the cost of disdain towards Nehru and Mountbatten—the former virtually held responsible for the Partition and the latter making it disastrous. Mahatma Gandhi, though, appears to be held on equal pedestal with Jinnah. A point is made that had he been in control of affairs with Jinnah, the outcome would have been different. Though many would find it difficult to align with this entire narrative, Shahid and Tahirah’s (who met with Jinnah on several occasions) first-hand account of events show a lesser-known side of Jinnah. Finality is hard to arrive at in such tangled historical debates, but how the book helps is by revealing the human side of Jinnah, although its treatment of Nehru is highly superficial. Away from the high-profile life of Shahid and Tahirah, Mumtaz and Mary remained absorbed in their ordinary yet poetic life, unless the Partition came knocking at the door.

The difference between the lives of the two couples, all throughout, has been the key to the balance of the book—capturing the ordinary and paramount at the same time. One thread ran in common though: making sense of the plight of Partition and changes it brought to their lives. Tahira reflected: “All I know is that the life I had before the Partition of India was as beautiful and as rich as it was afterwards.” Beyond everything, it brings into notice the futility of the exercise which was a result of political battles of a few, and maneuverings of the Raj. Tahira is on point in saying: “Bricks and mortar don’t matter…People do.” The process of reconstruction of the past is an enchanting exercise. Mishal invites readers to join her in this endeavour. Through her family, readers get a chance to ponder over yet another version of British India’s transition to Independence.

Views expressed are personal