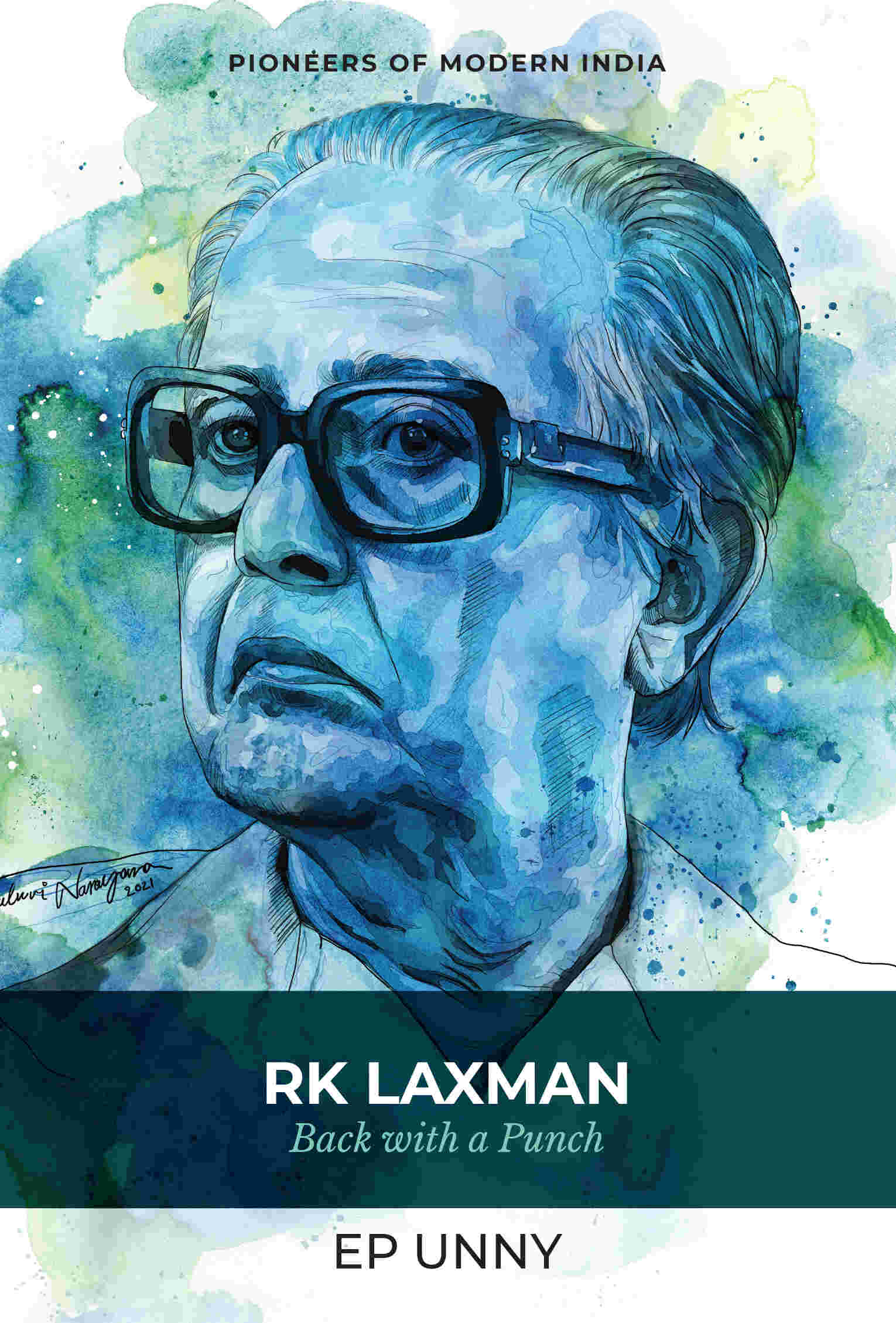

Back to spotlight, brighter

EP Unny, in the monograph ‘RK Laxman’, discusses how the evocative sketches by the Mysore-born legendary cartoonist have come to catch the present-day imagination — perhaps with an enhanced punch. Excerpts:

Laxman readers tend to associate their favourite Common Man with the single-column pocket cartoon 'You said it'. Few realize that this is the character's second home. He came from the big bad world of the editorial cartoon.

Icons transcend the boring details of origin and growth but fans shouldn't miss out on the legacy. The Common Man first appeared in 1950 and can count as contemporaries the cast of two all-time great comic strips—Peanuts born in 1950 and Dennis the Menace in 1951. Unlike Charlie Brown and Dennis, Laxman's man was never far from the world of news. There were no syndicating agencies or merchandising and licensing opportunities to sustain a comics industry in India. Indian cartoonists survived as newspaper employees and almost everything they did was news-driven. Laxman was no exception.

Long before TV, Laxman saw news as scenes playing out in the public arena. The cartoon wasn't complete without the viewers in the frame. You find a similar sprinkling of onlookers in the early Shankar cartoons as well. But the veteran quickly developed a privileged gaze that went with his location. This came naturally to the Delhi-based cartoonists who didn't merely view but witnessed news-making from a vantage point. Their comment had the stamp of authority that came from proximity. Laxman instead saw himself as a distant viewer from Mumbai, where there was no dearth of co-viewers. You just had to look around and you found a mini-India bustling past. Laxman picked his eager onlookers from this lot. The crowd in the cartoons eventually thinned down as national politics grew more Delhi-centric and distant to the Mumbai eye. Finally, a lone figure stayed on. That was our familiar man in the checked coat.

Everyman has traditionally been used by dramatists to convey the moral of a story. This is a dicey device for the cartoonist, who should be anything but preachy. Laxman solved this problem brilliantly. His protagonist never spoke a word. The next challenge was to give the character a physical form that suggested a pan-Indian identity. Taking away the voice was easy, but one can't reduce the muted man to a matchstick figure to bypass all evident specificities. Given Laxman's maximalist style, the character had to be fleshed out. Again, it must connect to the whole of India, which was the news footprint the cartoonist surveyed every passing day.

In his 1950 appearance, the bespectacled figure was labelled in all caps as 'COMMON MAN' to dispel any specific identity. One stand-out sign was the black cap he wore. Only certain classes of people in certain parts of the country wore a cap like that. The cap was kept aside whenever the Common Man switched to purely European clothes—suit, boots and baggy Chaplinesque trousers. It came back when he returned to the more regular Indian wear. Across the first Nehruvian decade the cap disappeared and reappeared much like the Prime Minister's own Gandhi cap. Whether there was a correlation is a matter best left to the researcher. Somewhere down the line the headwear vanished.

Common Man Finds a Second Home

By 1960 the little man settled down to what came to be recognized as his signature form. Wisps of hair over the ears, uncovered bald pate, round oversized glasses, checked coat and shoes without socks and to make his ethnicity suitably uncertain, the timeless unstitched Indian cloth called the dhoti—an attire common to many parts of the country. The protagonist had by then found its natural habitat— 'You Said it'. 'My diligently-planned single-column feature', is how the cartoonist describes it in his autobiography. Devoid of recognizable public personalities, Laxman revelled in the full freedom 'from the shackles of habitual realism, and indulged in a sort of political fantasy.'

The creator's unfettered joy didn't infect the creature. Unaware of his upgrade to freer ground, the common man carried on as befuddled as before, without a word. Mercifully silence wasn't a familial trait. Every once in a while, his wife joined him and she spoke her mind.

The Common Man went on to become the most recognizable Indian comic figure. Honoured with public statues in Pune and at Worli Seaface, Mumbai, and a commemorative postage stamp, he promoted Air Deccan, the country's first no-frills airline, as mascot. The standalone character's portability was evident early on and the creator was a beneficiary. Once, arriving late at night in Germany, on an invitation from Heidelberg University, Laxman stepped out of the airport into dimlit anonymity. He knew none and none knew him well enough to place him. As he looked around, up went a placard with the picture of the Common Man. The professor who had come to receive the cartoonist was suitably equipped. The famously silent Common Man made the introductions.

The much-interpreted silence has been broken once. In a sequential cartoon of 1954, the Common Man on an overseas visit is being harangued by a patronizing European on India's claim over Kashmir and Goa. After the long listen our man retorts, 'Supposing you tell me something about Kenya, Malaya, Cyprus…' The colonial relic beats a hasty retreat. Again, contrary to popular impression, the man isn't always placid. He almost gets physical once. He steps on a button that activates a mechanized clenched fist that flies out of the microphone, hits and stops the speaker who is evidently going on and on. The raw power of the hit is tempered by a mechanical interface. This goes well with the Laxman style of softening the blow, without pulling punches. The punch re-emerged after 23 years and how. You see the little man, sleeves rolled up, knocking out the grand old Congress party in the March 1977 elections that punished the ruling regime for the virtual one-party rule during the internal Emergency. This was the Common Man at his spirited best, the big citizen of a big democracy.

Barring the rare demonstrative surge, the man remains quiet. He seems to have yielded to the ways of the new state as early as the 1950s. You see him squatting on a bed of nails with yogic nonchalance or posing passively for a souped-up portrait by the budgetmaking finance minister. At the first Republic Day after Jawaharlal Nehru's death in 1965, the anxious ruling party made a gallant attempt to reboot the citizen. Laxman's response is a collector's item—a display cartoon where the Common Man appears twice. One of the two stood with the onlookers. The other occupied the pride of place on a decorated float driven by the new PM Shastri. This boost was as short lived as Shastri's prime ministership. Since then, the Common Man broadly mirrored the Indian citizen's plunge.

Along this free fall from participation to passivity, Laxman's protagonist shows striking moments of resilience. Ahead of the professionally geared mountaineers, our man in common wear is clambering up Mount Everest, trying to catch up with soaring prices. Decades later he is back to volunteer for the manned mission to the moon. One of the scientists details the volunteer's impeccable credentials: 'This is our man! He can survive without water, food, light and shelter…' You could add, and 'his own hard-earned money'.

Taxed to the Bones

If there is anyone Laxman hated more than the terrorist it is the taxman. In 1962 on the war with China, the cartoonist blames Nehru as much for the wartime levies as the military setback itself. The PM is shown at the head of his feuding party appealing to the public to unite and sacrifice. The cartoonist is the down-to-earth householder of Mumbai and not the high-sounding critic of Delhi. The Common Man is seen at his worst whenever he is called upon to shell out tax. By PM Nehru in 1962, Rail Minister Prof Madhu Dantavade in 1977 and PM Deve Gowda in 1997. On each occasion the protagonist appears denuded, covering himself with the day's newspaper, having handed over all he has, including his clothes and shoes.

Laxman seems to suggest that the working Indian's mission in life is to earn enough to pay the state, go broke and get back to the grind to earn all over again for the next round of well-meaning taxes, levies and cess. It is an endless Karmic cycle of submission to the taxman. Seeing the state as an economic oppressor, as much as a political meddler, is the hallmark of advanced societies of Europe and the US. The IRS (Internal Revenue Service) is a pet target of American cartoonists. The ultimate inevitability of death and taxes is a common thread that runs through these cartoons.

The taxman often comes across in these drawings as the companion of the scythe-wielding Grim Reaper and when the cartoonist is very angry, as the reaper himself. Laxman comes close to first-world cartooning in his aversion to tax hikes. He is certainly not the only Indian cartoonist who scowls at the tax collector. But he has done it every time with extreme intensity, depicting his protagonist with not a stitch on him, in utter humiliation, risking his quiet dignity.

This is the voice of the self-made expat in a big city when the state touches his hard-earned income. The voice was back every morning to raise similar issues that mattered to an urbanizing India. The tone was far from respectful. Worse, it was getting popular. Trouble wasn't far.

The Crown that Clowned

The last decade of the last century a familiar Delhi leader emerged in a dramatic makeover. Measured, methodical and a longtime member of the Parliament's upper house, an unlikely L.K. Advani emerged as a shrill voice of faith-led populism. In 1990, he led a widely televised road show called Rath Yatra (Chariot Ride) through the Hindi hinterland in an automobile spruced up as a filmy chariot. Laxman met this campaign with a simple prop. He gave the big campaigner a small crown that looked straight out of calendar art. The kind that belongs to garish mass-produced spreads of Indian mythological figures. In Laxman cartoons, Advani couldn't shrug off the ill-fitting headgear, even after he stepped out of the Toyota Rath.

The properly clad, familiar, lean, tall figure was shown donning this odd ornate crown through mundane everyday activities like parliamentary work, public meetings and diplomatic engagements. The incongruity was killing. And didn't go unnoticed by the leader's fans in journalism. More than a loose sally of admirers, Advani had a proper fan club in the capital, which saw a potential PM in their patron. A sudden buzz rose that cartoonist Laxman was losing his touch and must retire gracefully. Having done a great deal for Indian satire, he should now make way for youngsters, went the spiel. Younger cartoonists were no friends of Advani or his new avatar. Someone like Ravi Shankar was characteristically merciless. But none had the clout of Laxman. The worst fear of Advani fans was that the whole of Mumbai was behind its cartoonist. Political Delhi could no longer ignore Laxman, the prescient cityman.

(Excerpted with permission from EP Unny's 'RK Laxman'; published by Niyogi Books)