Antidote to a turmoil

Makarand Paranjape through his book ‘JNU’ stirs an intellectual discourse around how the university’s idea of nationalism, defined by suspicion and hostility, marks a shift from the ideas of Tagore and Gandhi who focused on ‘intermedial hermeneutics’

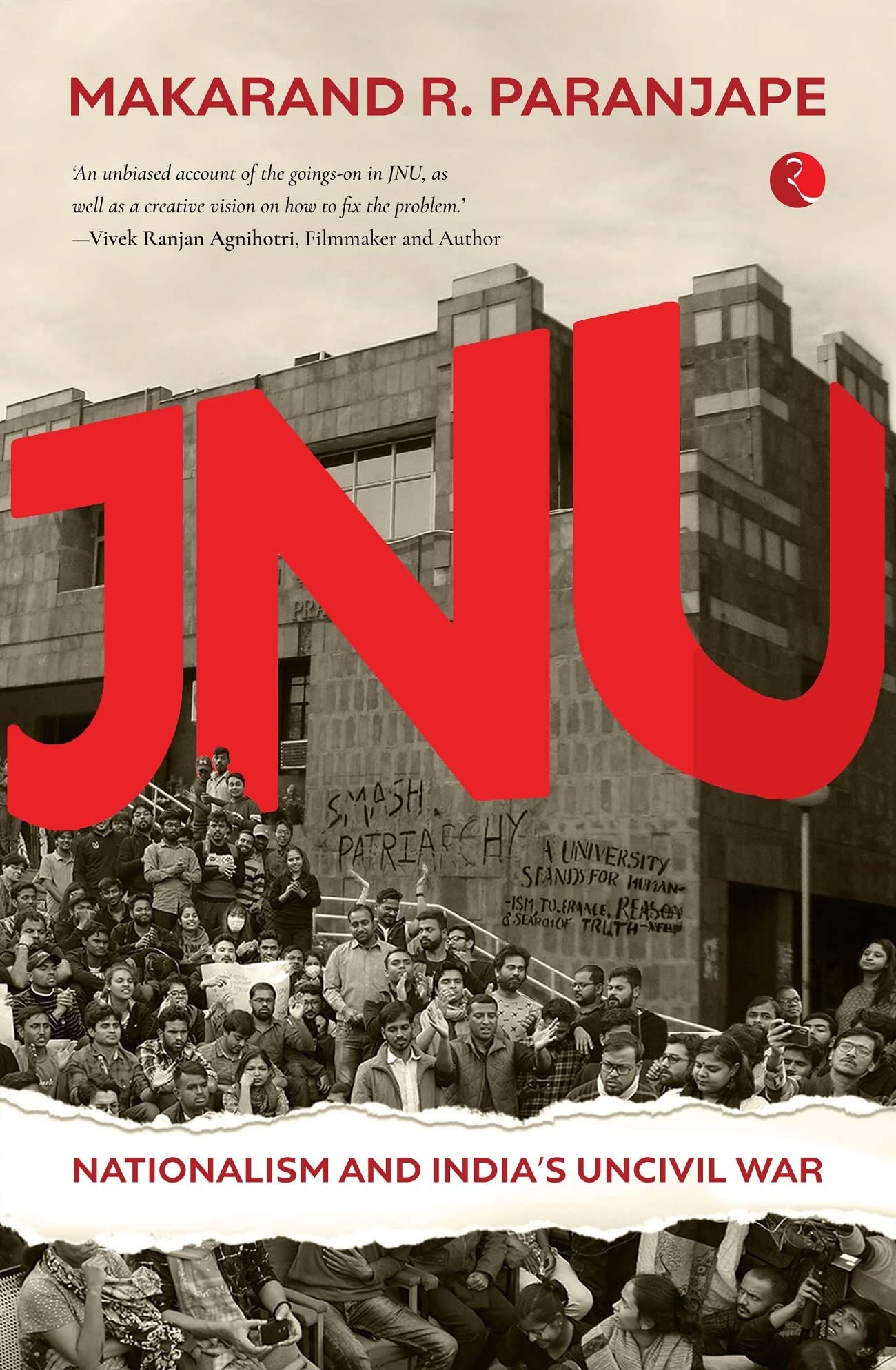

In penning 'JNU: Nationalism and India's Uncivil Wars', Makarand Paranjape, the senior-most professor of JNU and also perhaps the youngest PhD holder in the country at the age of 24 goes beyond the anecdotal or hagiographic to offer an insider's view on the institutional malaise which reached its nadir in 2016 when the JNUSU president was arrested for sedition, students took over the administration building, disrupted teaching and put up posters and programs for expressing solidarity with Afzal Guru. Although this was not the first time that students and the administration were locked in a bitter battle – this time the debate went beyond the campus, and an important section of the mainstream media built a narrative that was critical of the position taken by JNUSU and JNUTA.

It must be mentioned here that in the first two decades of its existence, the media had been generally supportive of the students' movement – but that was also because a broad consensus existed among the two thousand odd students, most of whom recognised each other by face, if not by name. This was also the time when the NSUI and ABVP were notable for their absence. There were the dominant and the not-so-dominant left groups of multiple hues, non-conformists, Free Thinkers and some who were aligned with the socialist movement of JP and drew inspiration from the writings of Lohia and Acharya Narendra Dev. The Right was singularly absent.

In many ways, the ideological debate in JNU also reflected the political composition of the Parliament, with the caveat that in an interesting role reversal, unlike in the Parliament where the Communists piggybacked on the Congress, in the campus it was the other way around. The Left accorded decent space to Nehruvian thought – and the CPI was always aligned with the Congress even during the Emergency. Even after the Emergency, when CPI decided to align with the CPM, Comrade SA Dange broke from the party he had founded, and aligned his newly formed ICP and UCP with the INC.

This perspective is important to place the book in its contemporary context. Spread over nine chapters, all of which make interesting reading, this review will focus on the first, fourth, fifth and eighth chapters for they bring out the many strands of the debate, as well as the intellectual depth of Paranjape's understanding, not just of JNU but of the nation as well. In the very first chapter, he is forthright in his critique of the state – and he avers that 'most political parties, regardless of their (ideological) beliefs are statist, if not status quoist. All of them push for greater bureaucratic and political control of our lives'. He then goes on to engage with Pratap Bhanu Mehta on the concept of Bhartiya. For Paranjape, the core of Bhartiyata was non-absolutism or anekantavada, implying that the ultimate truth and reality is complex and has multiple dimensions. In other words, no viewpoint can be ignored, or treated as pariah. Arguing against the Left-Liberal-Marxist perspective of the state, he posits Aurobindo's treatise 'The Renaissance in India' to 'turn new eyes on past culture, reawaken to its sense and import, and see it in relation to modern knowledge and ideas.

The core of the book (Chapter 4: Tagore, Gandhi and JNU) includes Paranjape's address at the 'Teach-in' of students where he spoke on 'Ideas rather than Ideologies: JNU's Alternative Performative'. This also explains why in the course of his online conversation in the Afternoons with an Author series at VoW, he stated quite explicitly that intellectual integrity and rigour were more important than ideological consistency. He makes the case for 'intermedial hermeneutics' – a dialogue that is not a polemic in which the two sides are hell-bent on vanquishing each other, but speaking to one another with a wish to learn and expand the frontiers of knowledge.

Describing the nationalism of Tagore, he points out that there were many distinct phases of Nationalism for Gurudev: conventional nationalism (1890-1904) Swadeshi agitation (1904-19070disillusionment with militant nationalism (1907-1916) critique of Imperialism (1917-1930) and the reconciliation of antimonies (1931-1941). In any case, the nationalism conveyed in his most popular poem talks about his Bharat in which the world has not been broken down by narrow domestic walls. With regard to Gandhi, the seminal text Hind Swaraj contained the kernel of his nationalism - based as it was on truth, nonviolence, bread labour, mutual respect, Hindu Muslim unity, caste and gender equality village autonomy and empowerment of the people, rather than the state. However, this model was rejected by his political heir and the Prime Minister on whom the university was named. For that matter, even Patel believed in a strong state and has always been known as the Bhishma Pitamah of the IAS.

There is another interesting linguistic factoid – the contrast between Azadi and Swaraj. While Azadi comes from the Persian word which meant manumission of a slave, Swaraj was about self-rule and self-governance. Therefore, in an epistemological sense, Azadi can only be given, whereas Swaraj can be achieved with self-effort. Of course, these days, much meaning can be read into this as well -Azadi would be part of the Abrahamic and Swaraj of the Indic tradition.

Let me now quote from three of the five epistles written by him (Chapter 5) to his colleagues at JNUTA. On February 19, 2016, he wrote to President JNUTA (Ajay Patnaik) protesting the commemoration of Afzal Guru under the false banner of an evening of poetry. On March 4, 2016, he wrote to Prof Rajat Dutta that 'talking and listening to all sections of our ideologically and socially diverse society is one of the demands of our times. Especially if we wish not to escalate the uncivil strife that threatens to engulf us. The third is to his colleague Ayesha Kidwai, when he states 'to me the fight is not (only) between opposing ideologies, but also between ideology and integrity.

In the eighth chapter (A nation united, a university divided) he talks of the visit of JNU's only Nobel Laureate alum Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee who had been critical of the government's decision to charge students with sedition. However, even though the students were keen to take selfies with him, not one had read his book Good Economics for Hard Times. This Paranjape felt was indeed a matter of lament. However, there is hope at the end of the tunnel. For there is an increasing number of voices which agree with him that the university needs a hermeneutics of trust and generosity, not suspicion or hostility. He asks of the JNU community 'If we cannot accomplish this on our own campus or put our own house in order so to speak, what right do we have to preach to others about the virtues of tolerances.'

Views expressed are personal