A nationalist of stature

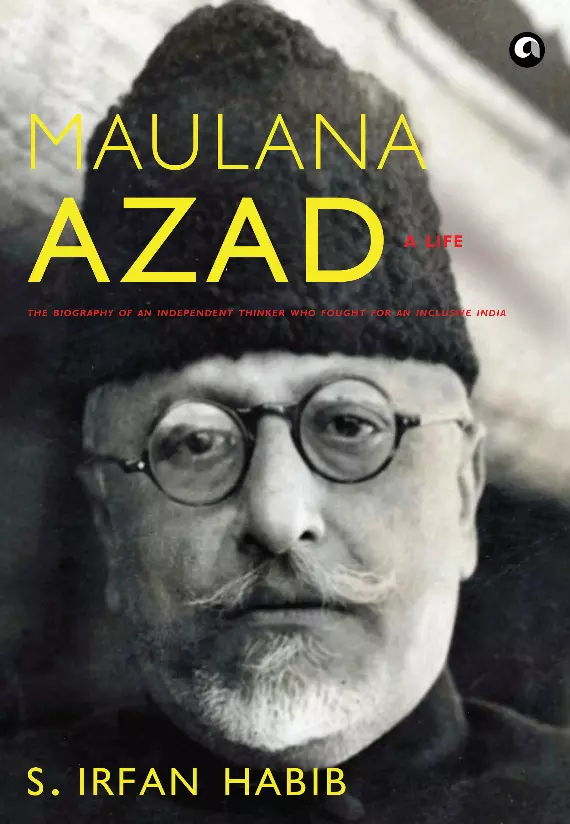

In the deeply researched, definitive biography — Maulana Azad — Irfan Habib provides a useful insight into the auto didact’s views on Islam and how those contributed to his rich and independent philosophy on nationalism. Excerpts:

Before we begin to discuss the above three together, let me digress, if one may call it digression at all, and talk about the birth and evolution of modern-day nationalism. It is well established now that the modern concept of nationalism is one of the by-products of the politics of democratization in Europe. The word ‘nationalism’ first appeared at the end of the nineteenth century and was used to describe groups of rightwing ideologists in France and Italy who were keen to brandish the national flag against foreigners, liberals, and socialists and in favour of that aggressive expansion of their own state, which was to become characteristic of such movements.

This is so close to what we are witnessing in India today. We got rid of European colonization using the ideological tools developed by them, however, the same liberating ideology has become a bane for us. Our nationalism today needs an enemy, and even a fellow citizen can be demonized to keep the country perpetually on the boil. Gandhi saw this in 1925 when he raised a fundamental question, while speaking in Calcutta: ‘Is hatred essential for nationalism? You may not love, but must you also “hate?”’

Even before nineteenth-century German and Italian unifications that concretized the idea of territorial nationalism, it was the French and American revolutions in the late eighteenth century that challenged the might of empires. The Americans got rid of the British empire and ‘the French defenestrated their own king…. After a few years of floundering as a collection of colonies united only by their determination to be rid of British rule, the Americans inaugurated a new idea of nationhood born of a unified people with common political and economic interests, under a system combining democracy with capitalism. Modern-day nationalism was born.’ It was the beginning of what followed in Europe in the nineteenth century with the emergence of the first proper modern nationalist figures like Count Cavour, Garibaldi, and Mazzini in Italy and the iconic nationalist, the Prussian Chancellor Bismarck. They developed a feeling of love for ‘their native land and soil, the traditional cultural heritage from their parents, and allegiance to the established authorities ruling their homelands, and converted them into a newly defined loyalty to a nation-state.’ This was also the period when the song ‘Deutschland Uber Alles’ (Germany above all others) replaced rival compositions to become the actual national anthem of Germany. In India we find a similar race to anoint a particular one over all others, with some rabid ones even challenging the national anthem.

We see the use and misuse of history in defining a certain brand of nationalism, which is not a recent phenomenon, even Maulana Azad coped with this malaise in the 1920s and 1930s. Eric J. Hobsbawm, the British thinker and historian, makes a connection in his book, ‘Nations and Nationalism’ since 1780, between history and nationalism and explains how history is reconstructed in a way that suits the ideology of nationalism and is essential to its construction. Hobsbawm compares the role of history to nationalism with that of the poppy to the heroin addict. This explains why in India today the past has become more relevant than the present or the future. Most of the political battles are fought to reclaim an imagined past, and to set right imagined historical wrongs, while the present seems to be perpetually in abeyance. This is one explanation for ‘why history in India has become the arena of struggle between the secular nationalists and those endorsing varieties of religious or pseudo-nationalisms’. Even anti-colonial nationalisms, like in India, which aimed to rid their nations of oppressive colonial regimes, used religion as a divisive tool to weaken inclusive nationalism. The demand from some Muslim leaders during the freedom struggle for the creation of Pakistan as a homeland for India’s Muslims rested on the then novel proposition that Muslims were a ‘nation’ entitled to their own territorial homeland in India. Religious nationalisms, both Muslim and Hindu, remained on the fringes of the freedom struggle. The former eventually divided the country while the latter kept weakening it from within. Romila Thapar explains it succinctly when she says that ‘what we take to be nationalism can be a positive force if it calls for the unification of communities’, as was being done by Gandhi, Maulana Azad, Nehru, Patel, and others, ‘but equally it can be a divisive and therefore negative force if it underlines exclusive rights for one community on the basis of a single identifying factor’.

Hannah Arendt, the German American political theorist, said about America in 1973: ‘This country is united neither by heritage, nor by memory, nor by soil, nor by language, nor by origin from the same…these citizens are united only by one thing—and that is a lot. That is, you become a citizen of the United States by simple consent of the Constitution.’ Many of us invoke the Constitution of India to define our national identity but a large section barely pays respect to the values enshrined in the Constitution. The economist Pranab Bardhan cites a speech by Barack Obama from 2009 where he says, ‘One of the great strengths of the United States is…we do not consider ourselves a Christian nation, [but] a nation of citizens who are bound by ideals and a set of values’ as enshrined in the Constitution. The Hindu supremacists today need to take a cue or two from the voices above and shun the path being followed by Erdogan in Turkey. ‘We’ve seen a very severe example of negative nationalism in the case of Germany in the 1930s when the Nazis propagated the idea of the purity of the Aryan race and the origin of European Aryans….’ Azad was aware of the dangers involved: ‘Nationalism, in its simplest form, has existed for ages. But the collective belief and ideas that the term brings to mind are the product of the new era of European civilization. It started as a defence for human rights and liberty, but has, today, become its greatest threat.’

All those aware of the dangerous implications of this variety of nationalism fought a relentless battle to keep India free from it. Maulana Azad was in the vanguard of the struggle to keep India united within the broad framework of inclusive nationalism.

He expanded on these ideas in detail as a youngish man of thirty-five when he presided over the Congress session in 1923. He talked of the natural laws that govern society, which are obscured for us due to our emotional biases; he stressed the importance of surmounting all differences of views and opinions to collectively strive for independence. He spoke about the amazing uniformity of laws of social life—quoting Omar Khayyam he said, ‘Life is the same story, repeated over and over again, with new names and new characters.’

Maulana Azad, as we know, was an Islamic scholar who was committed to his faith and its future. He was also a strong believer of pan-Islamic solidarity. His antipathy towards British colonial occupation was not confined to the fate of India alone—‘Azad’s concept of nationalism included not only the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent but embraced Muslims all over the world.’ This was when Azad was more concerned about pan-Islamic solidarity against the colonial regime, and not as worried about Hindu-Muslim unity. Thus, while articulating his anti-British strategy he stressed on the unity of the Muslim world to take this battle forward. Discussing the problems of ‘self-reliance’ and ‘self-awareness’ among the Muslims, Azad maintained that

Hindus can, like other nations, revive their selfawareness and national consciousness on the basis of secular nationalism, but it is indeed not possible for Muslims. Their nationality is not inspired by the racial or geographical exclusivity; it transcends all man-made barriers—Europe may be inspired by the concept of ‘nation’ and ‘homeland’, Muslims can seek inspiration for self-awareness only from God and Islam.

He moved away from an exclusivist vision based on geography very early on. Even his ‘Al-Hilal’, which was focused on Muslims and their future, stressed the inclusivist idea of Indian nationalism. We may go through a short account of this early phase, which will explain Azad’s drifting away from the exclusivist phase to a more inclusive ideal of nationalism.

When Azad was editing ‘Lisan al-Sidq’ from Calcutta (1903–1905), his press was at 14 Tara Chand Dutta Street—at the crossroad of Hindu and Muslim settlements in the city. This area was geographically situated between Bow Bazaar and College Street, which was the stronghold of the Bengali Hindu elite and nationalists. Machua, close to Tara Chand Dutta Street, was home to Bengali Muslims, Egyptians, Punjabis, Peshawaris, and Marwaris. When the Swadeshi Movement started, it became an active centre of mobilization with regular meetings at street corners.

It was here that Azad was truly exposed to the revolutionary fervour through groups like the Jugantar and Anushilan that shaped his political world view.

(Excerpted with permission from Irfan Habib’s ‘Maulana Azad’; published by Aleph Book Company)