A legend brought to life

Amit Ranjan, in his book ‘John Lang’, reconstructs the life of the Australian writer who was neither a rebel nor did fit into the Victorian space; he stood out among Anglo-Indian writers for his feminist writings

History is fickle

In what it decides to pickle,

To serve the posterity, and

What it lets trickle, through

its moment!

Amit Ranjan has shown that painstaking research and scholarship, and the ability to pun and recollect rhymes from times bygone can make an 'era' come alive. Anyone trying to understand how the East India Company imagined itself and the country they were ruling on behalf of a distant sovereign till 1858 should get to this book – for it holds the mirror to those times, and does not hide the cracks in the mirror as well as in the frayed frame which holds the mirror.

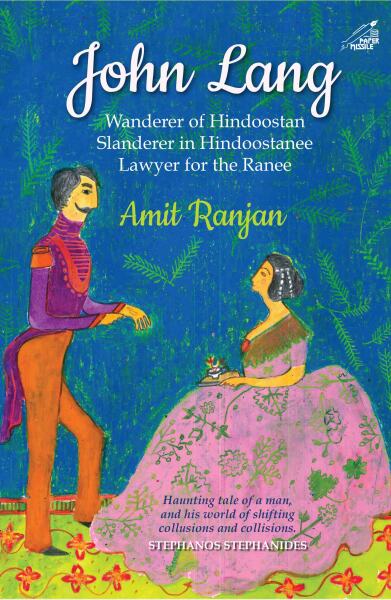

'John Lang: Wanderer of Hindoostan, Slanderer in Hindoostanee, Lawyer for the Ranee' resurrects the life, legend and scandal around the life of John Lang, the 19th century Australian-turned-Indian, barrister-cum-author-cum-maverick, who in his short life of 48 years produced no less than 23 novels/serialized fiction, one travelogue, some plays and five volumes of poetry – making him the first substantial Australian author. While Ruskin Bond was indeed the first to have brought John Lang out of the bushes by discovering his shrubbery-ridden grave in Mussoorie – and writing about him and his stories, the credit for the rediscovery of his corpus goes to the collaborative work of Rory Medcalf (of the Australian High Commission to India) and Australian scholar Victor Crittenden. This was the year 2005, and from here Amit Ranjan took over the muse — for him as well as for Alice Richman, who was buried in the Pune cemetery, hundreds of kilometers away from Mussoorie! The book also leads us to encounter some of the most notable characters at the time of the First War of Independence (to Indians)/Mutiny (to the British and their acolytes). These included Rani of Jhansi who had engaged John Lang as her Vakeel against the EIC as well as the noted rebel Nana Saheb, whose image was curiously replaced by that of Lala Jotee Persaud – a contractor and supplier of provisions to the EIC.

The book starts with a letter to John Lang Esq, who is currently at rest in the Camel's Back Road cemetery at Mussoorie. In a way, it traces the timeline and lifetime of Lang — filling him on details about his parents and grandparents, sons and daughters – both legitimate and illegitimate, as well as of his friends and friends turned foes, of the cases he won and lost, about his trips to jails in Calcutta and Vienna, the substitution of Nana sahib's portrait with that of Lala Jotee Persaud, the Fishers Ghost festival, his interlude with the Rani of Jhansi besides 'feminist' stories far ahead of the Victorian prudery!

Amit also places Kim's Kipling in the context of the Raj, and shows how Lang was different from the most well-known Anglo-Indian writer. For Kipling, 'East is East and West is West', and the construction of the Orient fed into the stereotype of palaces that gleam like sapphires in the sun, strange bazaars filled with forbidding men of a hundred races, events which are conjured by witchcraft, threats of wild bandits who roam the Khyber Pass, and strange land of princes and beggars and perfumed harem girls. Kim is a polyglot English orphan who works for an Afghan horse trader in Lahore and can camouflage himself both as a native and an Englishman. He is commissioned into the 'Great Game' where he manages to retrieve the documents from the Russians as well as his Lama mentor, but the course of action which Kim will take – the spiritual path of the Lama, or government espionage which will win him accolades and medals — is left to the reader's imagination. Kipling thus creates the dichotomy between the spiritual East, and the material West – and Kim is the crossover between the two. Lang, on the other hand, is quite different from Anglo-Indian writers in that he shows the British for what they are: cunning, selfish, manipulative and 'barbarians who dance with women who are not their wives'. He is not an outright rebel, but does not fit into the conventional Victorian space either — for his writings are 'feminist' and far ahead of his times.

Langs' fortunes were intertwined with those of Lala Jotee Persaud, a commissariat contractor par excellence who kept the British troops supplied with all the food and munitions they needed. Although he was charged with embezzlement in 1851, he won the case with Lang's help – and in 1857, he was the 'one person' who kept the British supply lines in order. He was then the 'hero' for the British, but he was also held in awe by the natives. After Lang won him the case, he presented his portrait to Lang, which the newspapers of the day thought was of Nana Saheb, and thus for several years, the revolutionary's frame was actually that of the person who collaborated with the EIC!

One could go on – and share so many anecdotes within anecdotes – for Lang not only knew his subject, he also had the great knack of making up a great story from run-of-the mill factlets. Ruskin Bond, who first discovered his grave, and also wrote about him in his popular columns, calls him a 'guppoo' — an untranslatable

word which means a teller of tales who revels in exaggeration and hyperbole — and Victor Crittenden, his biographer contends that Lang never told a story without improving it.

Amit Ranjan too, tells the story of Lang and his times, but he is not a 'guppoo' – he has taken painstaking effort to back each of his statements and contentions with empirical evidence and record – presenting a virtual kaleidoscope of the India before, during and after the epochal events of 1857!

Views expressed are personal