A catastrophic combo

Marya Shakil & Narendra Nath Mishra’s India on the Move examines the evolving discourse of nationalism in India, exploring the JNU protests, farmers’ movements, and Balakot strikes, revealing, in the process, tensions between blind patriotism and inclusive democracy

Time: Sometime in January 2021

Place: A WhatsApp group of friends, largely residents of New Delhi

Mahesh: What is the nation coming to? As if it wasn’t enough to block roads and inconvenience people, these farmers now have the audacity to replace the national flag with the Khalistan flag?

Sanjeev: Truly, this is anti-national behaviour at its worst. I do not think anyone should side with them now after what they did at the Red Fort.

Rakesh: I had been supporting the farmers’ protest all through, even though I personally faced a lot of inconvenience in travelling every morning on account of them having blocked roads and set up makeshift camps, but this is something else. I am ashamed that I supported them all this while.

Arun: But was it the Khalistan flag at all? The violence, of course, is to be condemned, but I think we must get our facts right before we make these sweeping statements and brand our farmers anti-nationals.

Sooraj: I don’t think after what has happened, you should be supporting them at all,

Arun. It was absolute anarchy on the streets. They broke through barriers, fought with the police, overturned vehicles and worst of all, delivered a national insult. Anyone supporting them now needs to look at their own credentials.

Mahesh: It is simple, the farmers have played into the hands of the Opposition. There is no other explanation.

An Uncertain Calm

27 January 2021

Silence prevailed at the Gazipur border with the farmers’ protest site looking like a pale shadow of its former self. A day earlier, amidst the Republic Day celebrations at Delhi’s Red Fort, a rally had turned violent after protesting farmers—mostly from Punjab and Haryana—broke through police barricades to storm the historic Red Fort complex. Having started out as a peaceful demonstration in November 2020 against three contentious farm laws, and after as many as eleven rounds of talks between the government and farmer unions had failed to break the impasse, the protest had taken a violent turn with agitators clashing with the police. Images of the violence were coming in from different sources at breakneck speed, with the moment being increasingly likened to Trump supporters storming Capitol Hill. A barrage of social media posts soon began to claim that the protesters had taken down the Indian national flag and replaced the tricolour with the Khalistan flag. The few voices condemning the violence but clarifying that the flag was not the Khalistan flag but the Sikh religious flag with the ‘khanda’—two swords—were quickly drowned. Public sentiment was turning increasingly negative; family WhatsApp groups, many of which had so far been sympathizers of the protesting farmers, had turned critics overnight. For the first time, farmers, who had always been looked upon as annadatas—food providers—were staring at an allegation of being ‘anti-India’, and of having ‘played into the hands of the Opposition’.

‘I was covering the farmers’ protest from the first day. I used to go live on Facebook from different locations every day. Thousands of people used to watch. They would ask in the comments how they could get involved and help the protest. However, the support for the protest, which was strong at the beginning, decreased after the events of January 26. People started going back home,’ says Debby Rai, a freelance video creator whose videos were keenly watched during the protest.

The Delhi Police, in a charge sheet that it would file later that year, would go on to state that there was a conspiracy to capture the Red Fort and make it the new site for farmer protests. It was alleged that the conspiracy had been hatched as early as November and December 2020, which had led to a huge increase in the purchase of tractors in Punjab and Haryana. On the other hand, a Punjab Vidhan Sabha committee that would be set up to investigate the alleged atrocities by the Delhi Police on farmers, youth and others from Punjab in the aftermath of the 26 January violence would go on to state that the melee was the result of a scheme hatched by the Delhi Police to defame the protesting farmers.

For now, the morale of the farmers who were protesting the three farm laws—Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, Farmers’ (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020—was completely shaken. The protesters were being viewed as rioters, their cause diluted, leaving those associated with the protest anxious. Farmer leader Pushpendra Singh reminisces how a young protester had walked up to him, grief writ large over his face. ‘We are being labelled as anti-national in our own country and society,’ he had said, with tears threatening to spill over. ‘We were anxious. The continuous news on television was creating doubts. There had been several attempts to break our unity. Misleading information was spread at many levels. First, the angle of Khalistan was introduced. Then, foreign conspiracies and foreign funds were alleged. It was said that China was supporting our movement. The sole objective was to speak against our movement in society and the country, preventing common people from joining us,’ Singh goes on to add.

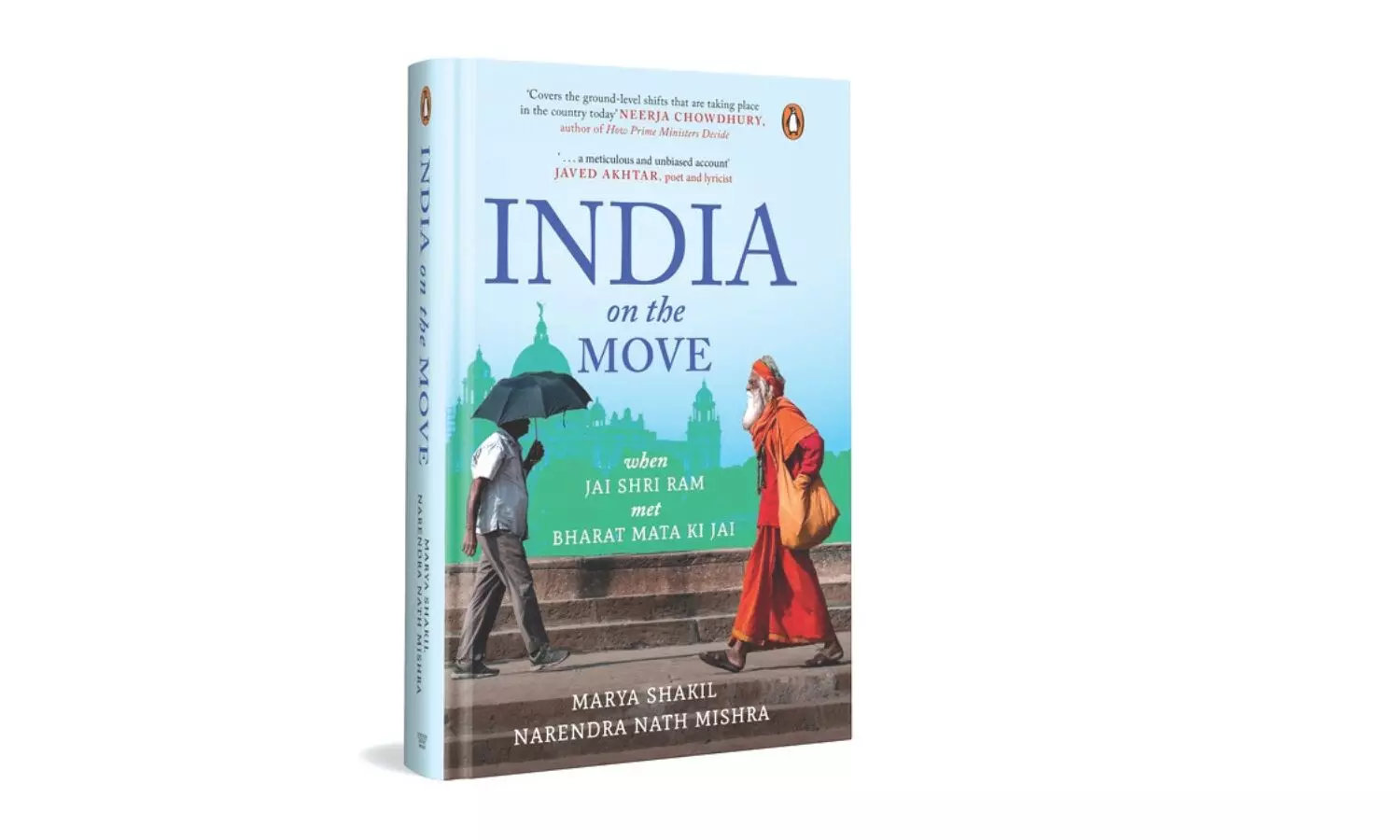

(Excerpted with permission from Marya Shakil & Narendra Nath Mishra’s India on the Move; published by Penguin)