Echoes of eternity

Blessed with serene monasteries and a remote village life echoing timeless wisdom and peace, Upper Mustang—a forbidden Nepali kingdom tucked away in the Himalayas—offers an other-worldly experience woven, paradoxically, with a deep human connection

The journey from the bustling tech city of Bengaluru to the mystical landscapes of Upper Mustang in Nepal was nothing short of a surreal adventure. It all started one hot summer afternoon as I made my way to the Kempegowda International Airport. The anticipation of leaving the concrete jungle behind and stepping into a land where time seemed to stand still was exhilarating. I had heard stories about Mustang, the forbidden kingdom tucked away in the Himalayas, and its ancient Tibetan culture. What I didn’t know was how profoundly the journey would touch me.

The flight to Kathmandu was smooth, and the city’s bustling streets and chaos greeted me like an old friend. I had a day to kill before my next flight, so I wandered through Thamel, Kathmandu’s tourist hub, mingling with travellers from around the world. There, I met Rajesh, a Nepali guide, who would later accompany me on my journey to Upper Mustang. Rajesh was a man of few words, but his eyes gleamed with the wisdom of the mountains.

The next day, we took a flight from Kathmandu to Pokhara, a city that feels like the perfect gateway to the Himalayas. Pokhara’s serene lakes and laid-back vibe offered a sharp contrast to the bustling energy of Kathmandu. Rajesh took me to his favourite tea house by Phewa Lake, where we sat by the water, sipping masala chai, watching the sun disappear behind the mountains. He told me stories of the Mustang region, of hidden caves, ancient monasteries, and people who still believed in the old ways. I was spellbound and couldn’t wait to experience it myself.

We began our journey to Mustang early the next morning. The first leg involved a jeep ride from Pokhara to Jomsom, a small town that serves as the gateway to Upper Mustang. The drive was bone-rattling, with roads that were more rock than tarmac, but the views more than made up for it. We passed through lush green valleys, terraced fields, and villages where children waved at us as if we were the most interesting thing they had seen all day. At one point, we stopped by a roadside stall run by an elderly woman with silver hair and a smile that reached her eyes. She served us hot noodle soup, a welcome respite from the cold. She asked me where I was from, and when I said Bengaluru, her eyes widened. “You have come a long way,” she said in broken English, patting my hand.

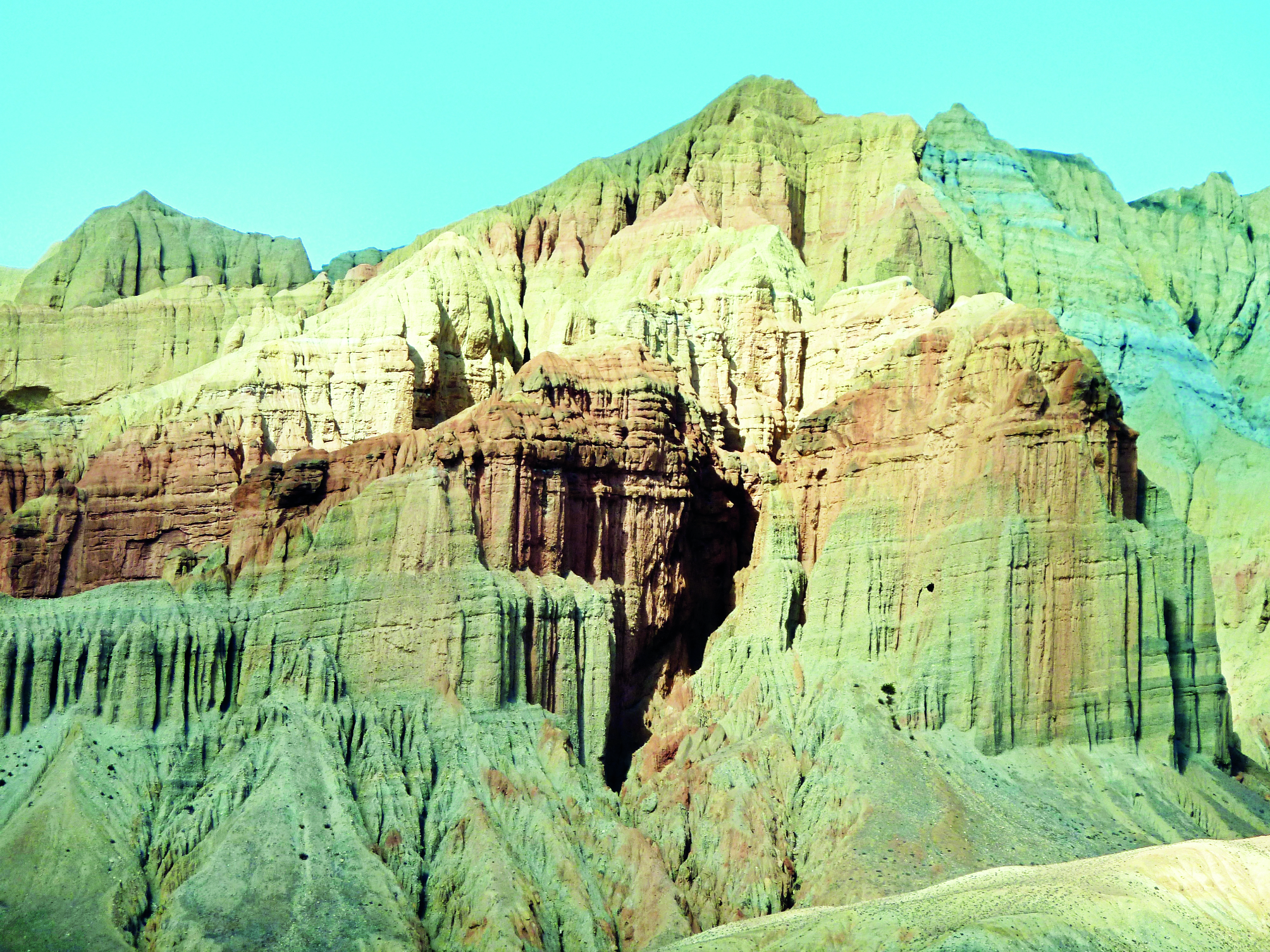

Jomsom greeted us with a biting cold, even though it was early autumn. We spent the night in a modest guesthouse, where the blankets were thick, and the air was filled with the smell of burning yak dung, the local fuel. The following day, we began the trek to Lo Manthang, the capital of Upper Mustang. The landscape changed dramatically as we moved further into Mustang. Gone were the lush green valleys, replaced by a barren, almost alien landscape of red and ochre hills. It was as if I had been transported to another planet. The air grew thinner, and the only sounds were the crunch of our boots on gravel and the occasional flap of prayer flags in the wind.

Along the way, we met a monk named Tashi, who was heading to a monastery near Lo Manthang. He was a gentle soul with a serene smile, and he invited us to join him for tea at a small teahouse on the trail. As we sipped our tea, he shared stories of his life in Mustang. He had been a monk since he was a young boy, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. He spoke of Mustang with a reverence that was contagious, describing it as a land where the past and present coexisted in harmony. Before we parted ways, he handed me a small prayer wheel and said, “May it bring you peace on your journey.”

As we approached Lo Manthang, the wind picked up, carrying with it the scent of dry earth and sage. The walled city rose before us like a mirage, its ancient structures standing tall against the harsh landscape. Lo Manthang was unlike anything I had ever seen. The narrow streets were lined with whitewashed houses, and the air was thick with the sound of chanting from the monasteries. We found a guesthouse run by a man named Dorje, who welcomed us with a hearty meal of dal bhat and tsampa, a traditional Tibetan barley

dish. That evening, Dorje took me to a rooftop overlooking the city, where we watched the sun set behind the Himalayas. He spoke of his ancestors who had lived in Mustang for generations, their lives intertwined with the mountains and the skies.

The next day, I visited the ancient monasteries that Mustang is famous for. The walls were covered in vibrant murals depicting scenes from Buddhist mythology, and the air was thick with the scent of incense. I met an elderly monk named Sonam, who was busy repairing a centuries-old statue. He spoke little English, but his eyes told a story of devotion and peace. He allowed me to help him with his work, showing me how to carefully clean the delicate statue. I felt a profound sense of humility and gratitude as I worked alongside him, knowing that I was part of something much larger than myself.

One of the most memorable experiences was a visit to a remote village where we were invited to a local festival. The villagers, dressed in their finest traditional attire, welcomed us with open arms, offering us homemade chang, a barley beer. The music was lively, and everyone, from the youngest children to the oldest elders, danced with abandon. I joined in, laughing and spinning with strangers who felt like family. A woman named Pema took my hand and taught me the steps, her laughter ringing in my ears. She told me about her life in the village, how she had never left Mustang, but how she felt content with what she had. “We have the mountains,” she said, looking around with a smile. “What more could we need?”

As the festival drew to a close, we were invited to a local home for a meal. The house was simple but warm, with a wood-burning stove in the centre and walls adorned with family photographs. Our host, a man named Karma, served us a feast of local delicacies, including yak meat and momos. He told us about his family, how his sons

had moved to Kathmandu for work but returned to Mustang whenever they could. “The city has its charms,” he said, “but Mustang is home.” I felt a pang of envy, knowing that I would soon have to leave this place behind.

The trek back to Jomsom was bittersweet. I felt a deep sense of connection to Mustang and its people, and I knew that I would carry their stories with me for the rest of my life. On the final day, as we made our way back to the jeep that would take us to Pokhara, Rajesh handed me a small stone. “A piece of Mustang,” he said with a grin. I tucked it into my pocket, feeling a lump in my throat.

The journey back to Bengaluru felt like waking up from a dream. As the plane descended over the city, the familiar skyline came into view, and I was filled with a sense of gratitude for the adventure I had experienced. Mustang had touched me in ways I hadn’t expected, and I knew that its memories would stay with me long after I had returned to the routines of daily life. The people I met, the stories I heard, and the landscapes I witnessed had left an indelible mark on my soul, a reminder that there are still places in this world where time stands still and life is lived in its purest form.

Back in the hustle and bustle of Bengaluru, I find myself often closing my eyes and imagining the windswept valleys and ancient monasteries of Mustang. I remember the warmth of the people, the taste of that first cup of tea by Phewa Lake, and the weight of the prayer wheel in my hand. And I know that, someday, I will return to the land where the past and present dance together in the shadow of the Himalayas.

The writer is a freelance travel journalist