Sartorial Threads of Tradition & Time

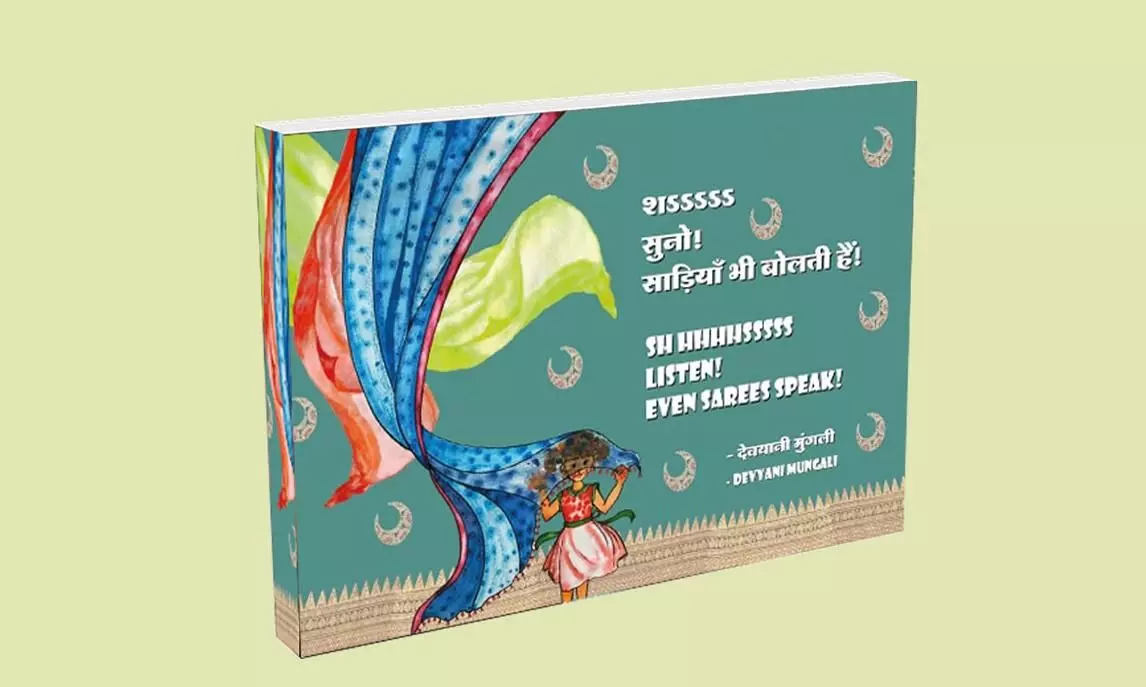

An illustrated bilingual gem, Sh..hhhhssss Listen! Even Sarees Speak by Devyani Mungali celebrates India’s saree traditions with the help of rich storytelling, fine understanding of artwork, and profound cultural insights. The book is an honour to handlooms, heritage, and the personal memories woven into every drape of India’s most revered traditional attire

The genre, the subject, the design and the format are quite different from what I normally review each week; usually a book of fiction, nonfiction or translation submitted for the VoW book awards in one of the above categories. However, the moment I received this illustrated book ‘Sh..hhhhssss Listen! Even Sarees Speak’ and turned the pages, I knew that this was a rare ‘one-of-its-kind’ offering. The book is a labour of love by educator Devyani Mungali, who has made a name for herself as a distinguished writer of meaningful books for children with themes drawn from our own legends, cuisines, sartorial expressions, cultural spaces and environment. Interspersed among the pages are ‘pop-ups’ which will reveal a magical weave when you shine a flashlight under them, preferably in a dimly lit room to capture the effect.

This bilingual book, in Hindi and English, with superb illustrations begins with the map of India on which 34 sarees – from Kashida in J&K to Kasavu in Kerala – are on display, thereby making it one of the most colourful and interesting maps of our country. This is followed by a narrative by a young girl who shares her conversations with her granny, her mother and her aunts about the sarees they wear. She learns that the saree of each region is a mark of identity and pride, and carries within its weft and warp, the passion, commitment and hard work of the weaver.

I am delighted to mention that the very first saree in this book is from Murshidabad, the district I was privileged to helm exactly three decades ago! Garad is the undyed white silk saree from West Bengal with a broad red border and pallu. The silk used to weave the Garad is not dyed, which keeps the purity factor intact, and lends a fine texture to the finished product. We next move to Kanchipuram in the south (Tamil Nadu) where bright purple and pink Kanjeevarams cast a spell on all those who get to see this ‘magical saree with many golden and pink peacocks’ which keep prancing and dancing with gay abandon all the time. Other popular motifs on this saree include temple architecture and mythological figures like Yazhi (elephant head mounted on the body of a lion). The pallu and the borders of Kanjeevarams are woven separately before being joined together.

We then move beyond the borders of India to learn about Gayatri Devi, the princess of Cooch Behar and the Maharani of Jaipur. It was she who first draped the chiffon fabric as a saree while on a soiree to Europe. Initially produced in France for the ‘noblesse oblige’ it has now become popular across the subcontinent for its shimmer and versatility.

Needless to say, the first three – Garad, Kanjeevarams and Chiffon – are sarees for the elite. The working women in the country prefer the more affordable and colourful synthetics, which are mass produced in Surat. They have vibrant designs, patterns and colours catering to the diverse preferences of women.

A Kalighat painting illustrates the Kantha – a special embroidery craft popular across West Bengal, Odisha and Tripura. Traditionally, old garments are put together using small running stitches, creating a unique effect by changing the density and length of the running stitches. The Patan Patola saree traces its origin to Patan in Gujarat. Patola sarees are about precision and perfection as the vertical and horizontal yarns are tied and dyed separately, and then woven together to create the most intricate pattern and design. The preferred base colour is maroon, and the motifs are usually inspired by nature – elephants, lions, peacocks, parrots, flowers and trees (peepal), kalash (holy vessel) and Rani-ki-Vaav, a historical landmark of the state. While talking about Patan Patola, we also learn about the differences between the ‘seedha pallu’ and the ‘ulta pallu’ drapes.

The saree of Kerala is called Kasavu, a ‘must’ during the Onam celebration, when Mahabali visits his erstwhile subjects to check on their welfare. Onam is never complete without a colourful Rangoli, flower arrangements, incense, and the very elaborate ‘Sadya feast’ with over twenty five different dishes, including Payasam served on a banana leaf. Traditionally the Kasavu saree were plain white with a golden zari border. The modern version has zari woven into intricate gold patterns with Kerala temple murals or Kathakali dance faces which are printed or painted. It is also the most important part of the Mohiniattam dance attire.

While Onam marks the onset of autumn in the South, Assam marks the arrival of the spring and the Assamese New Year with the celebration of Rongali Bihu – an occasion marked by song, dance and festivity. Women don a new Mekhela Chadar: the Mekhela is draped waist downward (like a sarong) and the top portion is the Chadar (called Sador), a long piece of cloth that covers the chest and the back and firmly tucked into the Mekhela. As it is a two piece garment, the length of the mekhela is shorter than that of a saree!

Last, but not the least is the description of the Nauwari – the nine yard long saree of Maharashtra with three distinct drape designs: the Koli, Brahmani and the Lavani style. Tucked at the back women have found this compatible with all kinds of work – from domestic chores to farm fields as well as on the battlefield. The illustration for Nauwari by Raja Ravi Verma features a woman from a royal household holding a Puja offering on her way to the ‘sanctum sanctorum’ of a family temple.

However, this is not the end, but the beginning of a journey, for the author asks the young protagonist to ‘open the old wooden chest’ of sarees, and ask the details about each one of them from grandmothers, maternal and paternal aunts, elder cousins and family friends. Unlike the mass produced ‘uppers’ and ‘lowers’, so much thought has gone into each and every creation. Moreover, in most cases, sarees are purchased on an occasion: an engagement, a marriage, an anniversary, a festive occasion, a visit to a place of pilgrimage, or as a return gift, and each of these has a memory.

Just one small point – a boy should also have been featured in the story line, for they too should take great pride in this tradition and ask themselves – why have the men given up on their traditional wear which in any case is so much more comfortable than the stiff formal attire which has been accepted without question.

Before closing, let me suggest that it is time for the men of this country to take ownership of their sartorial selves! And so even as I recommend this book to women and men of all ages, here is a request to Devyani: please have another lovely book for the traditional dresses worn by men as well!

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature