A vivid kaleidoscope

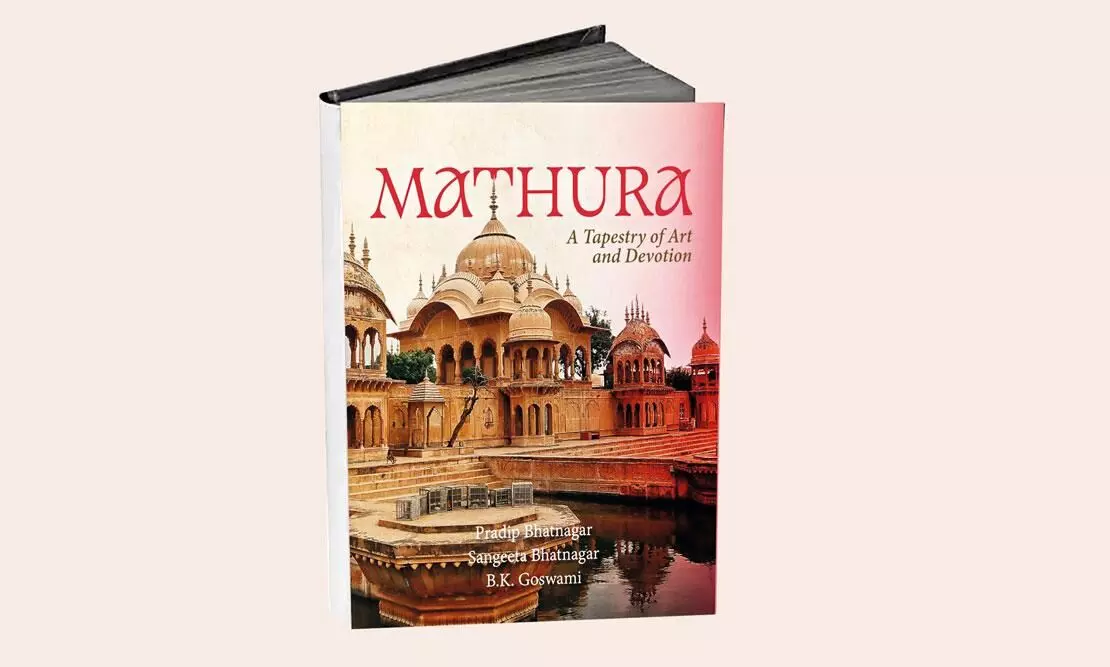

A visually rich exploration of Mathura’s spiritual, historical, and culinary heritage, ‘Mathura: A Tapestry of Art and Devotion’ by Pradip Bhatnagar, Sangeeta Bhatnagar, and BK Goswami brings alive Krishna’s land through art, devotion, and delectable flavours

The visual odyssey on one of the world’s oldest living cities, supplemented by a section on the culinary delicacies of the city, has been brought together by Pradip Bhatnagar, Sangeeta Bhatnagar, and BK Goswami in Niyogi Books’ wonderfully produced and elaborately illustrated book Mathura: A Tapestry of Art and Devotion. While Pradeep Bhatnagar and BK Goswami are both UP cadre officers with an intimate Mathura connection, Dr. Sangeeta Bhatnagar is the author of Dastarkhan e Awadh—a text widely acclaimed by gourmets and food critics alike.

The message from the MP, Hema Malini, talks about the ‘plethora of magical moments and experiences to be explored in the areas surrounding Mathura and Vrindavan,’ while the Foreword by Acharya Srivats Goswami calls the Braj (Mathura) Mandal ‘the unique centre of India’s culture and civilization where polity, economy, literature, arts, and culinary traditions can be traced as far as history can take us.’ Even as the Vedic, Buddhist, and Jain traditions left their indelible imprints on the land, the defining and everlasting association of Mathura is with Krishna, or Kanha, and his beloved Gopis, led by Radha. As the authors say, this is what ‘divinized the entire landscape of Braj.’

BK Goswami introduces the book with the famous aphorism from the tenth chapter of the Bhagwad Geeta (BG): Aham atma gudakesha sarva-bhutashaya-sthitah, aham adish cha madhayam cha bhutanam anta eva cha (‘O Arjun, I am seated in the heart of all living entities. I am the beginning, the middle, and the end of all beings’). Goswami describes Krishna as ‘a man in love and a God in his compassion.’ The Mathura–Vrindavan was the birthplace, the playfield, and the karm-bhumi of Krishna. But when Krishna left for Dwapar to establish a new city for his Yadav clansmen, it became part of Magadh under the Mauryas, and the city got a distinct Buddhist flavour, which is reflected in the writings of the Chinese scholars Fa Hein and Huen Tsang. The archaeological findings of Alexander Cunningham, who explored the sites as early as 1853, also confirm the Buddhist-Jain influences.

At the turn of the first millennium, the city faced plunder and pillage from Mahmud of Ghazni (998–1030 CE) and Sikander Lodhi (1489–1517), but there was a peaceful interregnum of a hundred and twenty years (1530–1660 CE) during the reigns of Sher Shah Suri, Humayun, Jehangir, and Shah Jahan. This was the period when the saints of the Bhakti movement—Vallabhacharya and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu—visited Mathura and started the worship of Krishna as practiced in the region today, including the Raas Leela and the parikrama. They set the ritualistic narrative for the devotees, which continues to the present day, in which every art form is employed to please the Lord: music, dance, painting, floral art, embroidery, stitching, cooking, woodcraft, and metalcraft. These include Sanjhi, Pichwai, and Kanhai paintings, Phool Bangla, the Charkula and Mayur dances, besides the Raas. The text on these is embellished with beautiful pictures, which is what makes the book so alluring.

However, when Aurangzeb became the Emperor, he reversed the policy of his forebears, began the demolition of temples, and changed the name of Mathura to Islamabad and Vrindavan to Mominabad. With the disintegration of the Mughal empire, Mathura came under the tutelage of the Jat rulers of Bharatpur and then the Marathas. But after the defeat of the Scindias in 1803, the area came under the British. From 1832, Mathura became the administrative headquarters of a district under the Agra Division. This was the period that saw the building and restoration of some of the most revered temples of Mathura and Vrindavan: Dwarkadheesh in 1813, Rangji in 1851, Banke Bihari in 1864. The establishment of rail links in 1875 to Hathras and Mathura-Vrindavan in 1889 added to the number of pilgrims manifold, and the city witnessed a cultural and spiritual resurgence, which gained further momentum post-1947 when the Keshav Dev temple was built over three decades—from 1950 to 1982.

The next chapter is on the legend of Shri Krishna. It is aptly illustrated by images of Vasudev crossing the Yamuna with the infant Krishna, the young Krishna holding the Govardhan mountain on his little finger, besides stories from his infancy to childhood and adolescence when he is frolicking with the lovelorn Gopis.

The authors rightly point out that no book on Mathura can be complete without a reference to the Braj Bhasha, popularized by Amir Khusro (1253–1325) and saint-poet Tulsidas (1532–1623), whose Ramayana and Hanuman Chalisa are now an integral part of Hindu folklore. The region in which the Bhasha flourished was the Brajbhoomi, which includes the city of Vrindavan. One clear distinction between Mathura and Vrindavan is that the latter has always been a Hindu city with no archaeological findings (so far) of the Buddhist and Jain traditions. Vrindavan is a spiritual centre with its numerous ashrams (religious retreats for holy men), dharmshalas (rest houses for pilgrims), and gaushalas (cow shelters), besides, of course, the magnificent temples, including the ones built to honour Madan Mohan and Radha Mohan. There is a special reference to the very well-organized ISKCON temple at Vrindavan, which attracts devotees from across the world.

The two main festivals of Braj are both connected to the Krishna legend: Holi is a 45-day affair in Mathura, commencing from Basant Panchami, which marks the onset of spring in early February, to the Purnima (full moon) day of Phalgun. Each hamlet—Barsana, Nandgaon, Baldev—has its own unique flavour of Holi, besides, of course, the community Holis in the temples of Mathura and Vrindavan. Next only to Holi is the celebration of Janmashtami, held on the eighth day (Ashtami) of the Bhadra (autumn) month. The main celebration is held in the Krishna Janmabhoomi temple, which is believed to be the site where the prison cell in which Krishna was born existed.

But apart from temples, festivities, and museums, Mathura is also known for its culinary delicacies, including the Mathura Peda, which has a geographical indicator to mark its unique and distinctive character. Then there is the tradition of chappan bhog—literally 56 dishes, one for each of the eight prahars (three-hour cycle) of the seven days when Krishna saved the city from Indra’s torrential rain by holding aloft the Goverdhan mountain. Goddess Laxmi is said to preside over the temple kitchen during the preparation of the bhog. Then there is the street food: the famous kulhad milk cooked on slow fire with thick layers of malai, buttermilk with its sweet variation of lassi and chhach, rabri (a preparation of condensed milk), khurchhan (scrapings from large vessels in which milk is cooked). The all-time breakfast favourite is jalebi—fermented batter mix of maida (refined flour), besan (gram flour), and water, fried in ghee (clarified butter) and dipped in sugar syrup.

Reading the review may inspire you to visit Mathura, delve into the divine legends, and enjoy the delicacies. But before you do that, visit your local bookstore or place an online order for this book, which will enhance your Mathura experience manifold. It is truly a tapestry of art and devotion!

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature