A paradigmatic shift

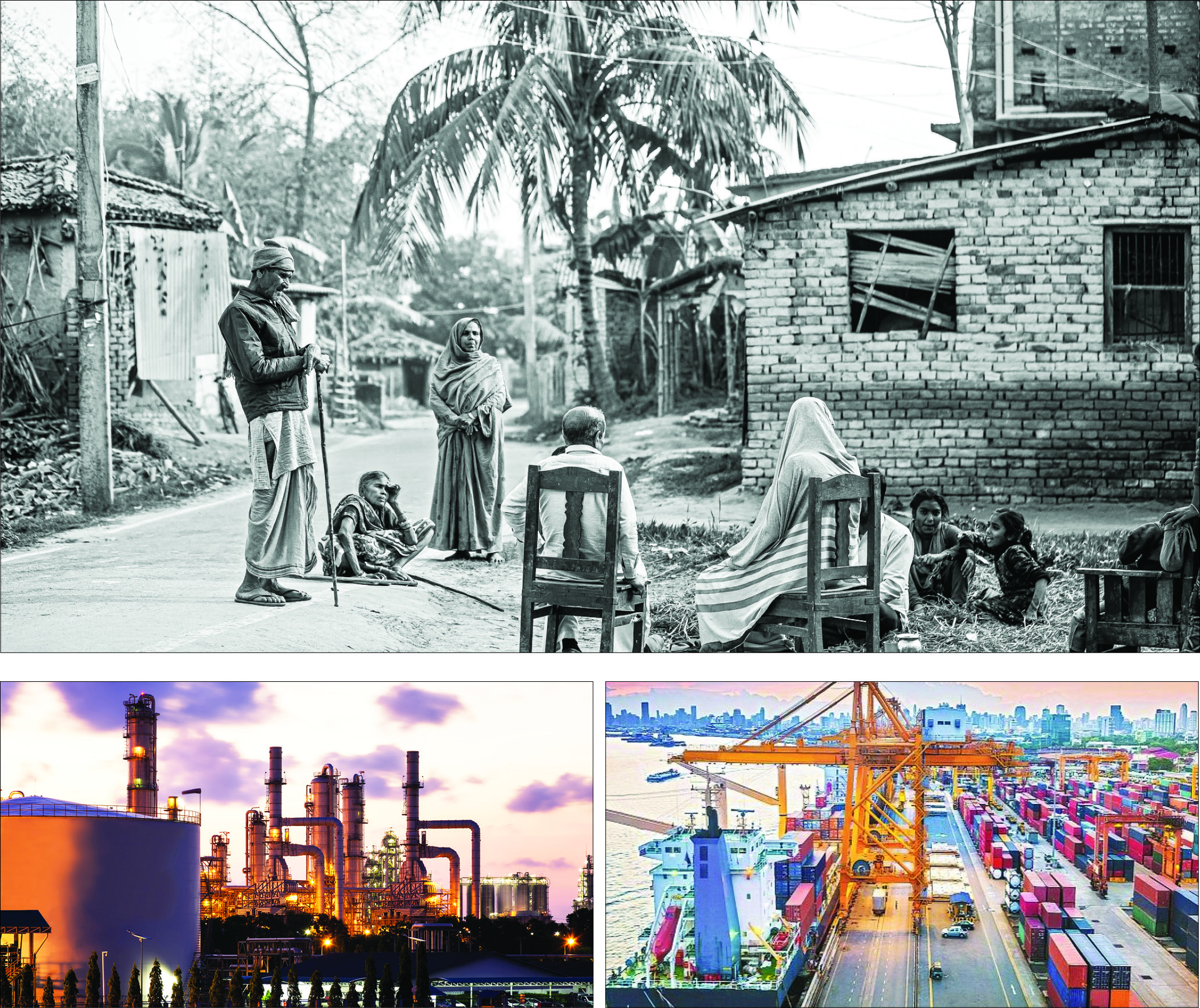

While the success of the landmark 1991 economic reforms ensured that the Eighth Plan far exceeded its growth target, the parallel focus on human development also curtailed poverty, generated employment, and promoted equality

The Eighth Plan was launched in 1992 in the midst of the unfolding of the massive economic reforms from 1991. We may recall that India faced an economic crisis, with the balance of payments crisis being at its centre. India was left with foreign exchange reserves of about USD one billion, which was enough to pay for two weeks of imports. On the political front too, the Chandrashekhar government, which came to office in November 1990, could survive for barely six months. For these reasons, 1990-92 was a period of only Annual Plans, and the Eighth Five-year Plan was launched in 1992.

The events of 1991

As mentioned above, India faced a balance of payments crisis in 1991, which also coincided with India’s credit rating being downgraded by Moody’s. India was also facing political turmoil. In such a scenario, India had no choice but to mortgage 47 tonnes of gold to the Bank of England to raise USD 400 million. India also had to seek financial assistance from the World Bank and the IMF, which was made available on conditions of structural adjustments and economic reforms. On top of this, the political situation was further worsened by the collapse of the Chandrashekhar government, and the assassination of ex-PM Rajiv Gandhi during the campaign.

Against such a backdrop, elections were held in 1991, in which Congress emerged victorious, and PV Narsimha Rao became the Prime Minister and Manmohan Singh was appointed as Finance Minister. Together, they began the biggest liberalisation of the Indian economy in 1991, which included dismantling of industrial licenses and controls, slashing of excise duties and import tariffs, simplified FDI rules, reforms in the banking system etc. The ‘epochal budget’ presented by Manmohan Singh in July 1991 set the ball rolling. In November 1991, the World Bank and IDA extended a loan/credit of USD 250 million each (a total of USD 500 million) as part of the structural adjustment plan. It was in this backdrop that the eighth five year was launched.

Key features

As noted above, the Eighth Plan was launched in the backdrop of the ‘epochal’ budget presented by Manmohan Singh in the previous year. In the words of the then Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission, the Eighth Plan was different because of these changes. To quote: “This makes it a Plan with a difference. It is a Plan for managing the change, for managing the transition from a centrally planned economy to market-led economy without tearing our socio-cultural fabric”.

It appears that the planners were acutely aware that the market alone could not address the core development challenges of India, such as employment generation, poverty eradication, removal of illiteracy etc. Hence, there was an equal emphasis on ‘Human Development’, which was stated as the ‘ultimate goal of the Eighth Plan’ in the Foreword to the Eighth Plan by then Prime Minister Narsimha Rao.

The salient features of the Eighth Plan were:

* Indicative Planning, where long-term strategic vision was to be stated, with roles of public sector and other sectors clearly defined: public sector to focus on strategic, hi-tech, and essential infrastructure while allowing private sector entry into other areas;

* ‘Human Development’ was to be the core of the plan, with priority areas being health, education, literacy, and basic needs such as drinking water, housing, and welfare of the weaker sections;

* Infrastructure development, with a focus on transport, communications, and power;

* Financing of the plan to be non-inflationary to avoid the pitfalls of the sixth and seventh plans: increasing resource mobilisation and reducing wasteful expenditure;

* Increasing the involvement of the people in implementation of the plans by strengthening of panchayats and urban local bodies, and by increasing the involvement of NGOs and voluntary agencies;

* Generating rural employment through rural works: shift from relief type of employment to one which produces durable assets such as rural roads.

The plan proposed a growth rate of 5.6 per cent per annum with a total outlay of Rs 7,98,000 crore. Out of this, public sector outlay was to be Rs 4,34,100 crore, which was about 50 per cent of the total outlay. The balance was to be financed by the private sector. Of the public sector outlay, 21 per cent was allocated to agriculture and irrigation, 27 per cent to power, 21 per cent to transport and communications, 22 per cent to the social sectors and 10 per cent to industry. Of the public sector outlay, Rs1,86,235 crore was to be for the States and UTs and Rs 2,47,865 crore for the Central Plan. The plan was to be financed primarily with domestic budgetary resources (86 per cent), external financing (5 per cent) and deficit financing (9 per cent).

Some of the other important macro aggregates proposed were: investment of 23.2 per cent of the gross domestic product, incremental capital ratio (ICOR) of 4.1, domestic savings at 21.6 per cent of gross domestic product and foreign savings at 1.6 per cent of gross domestic product.

An analysis

As noted above, market forces and the private sector were given equal importance in the growth process. Two areas in which the 1991 reforms were pathbreaking were industrial policy and international trade. It may be recalled that the ‘Statement of Industrial Policy’ of July 1991 had abolished licensing, done away with entry restrictions on MRTP firms and removed the public sector monopoly in most sectors except a few strategic ones. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) up to a level of 51 per cent was made automatic in all sectors except a negative list. In international trade, the OGL system was simplified and most items could be imported without a license except a small number on a negative list. Tariff rates were lowered and the tariff structure was rationalised.

At the same time, human development was not lost sight of, with a continued focus on rural development, rural employment generation, poverty eradication, removal of illiteracy, health for all and basic minimum needs of the poor.

As it turned out, the Eighth Plan was a success and the GDP grew at 6.8 per cent against the target of 5.6 per cent. This was the highest since independence. It was all the more impressive since it was achieved with a much lesser proportional outlay in the public sector and a high outlay in the private sector.

The Eighth Plan also succeeded in reducing the poverty levels from 36 per cent in 1993 to 26 per cent by the end of the Plan. This confirmed that the emphasis on human development was not misplaced.

Conclusion

The Eighth Plan was a trendsetter in many ways, and took forward the liberalisation impulse and economic reforms that began in 1991. The reforms yielded quick results and the GDP growth rate of 6.8 per cent was the highest recorded since independence. The eighth plan also put India on a new growth trajectory, with the hopes of better results in the areas of employment generation, poverty reduction, and more equality in the future.

The writer is Addl Chief Secretary, Dept of Mass Extension Education and Library Services, Govt of West Bengal.