Two Biographies

'Sri Aurobindo' by Roshen Dalal and 'Bondhu' by Kunal Sen are two unputdownable biographies among the Valley of Words’ shortlist for best non-fiction books in English, which document the lives of the two iconoclasts and corresponding personal, historical contexts

From Rajiv Dogra's 'Durand's Curse' to 'Wasted' by Ankur Bisen, Ishtiaq Ahmed's 'Jinnah' and Mrinal Pande's The History of Hindi Language Journalism in India — the list of VoW's selection for the best of non-fiction in English has evoked both interest and scope for further research into the concerned domain. Each one of the books mentioned above has touched upon an issue that is important to our understanding of how contemporary India has been shaped by historical currents, personalities, institutions, technologies, and of course the political economy.

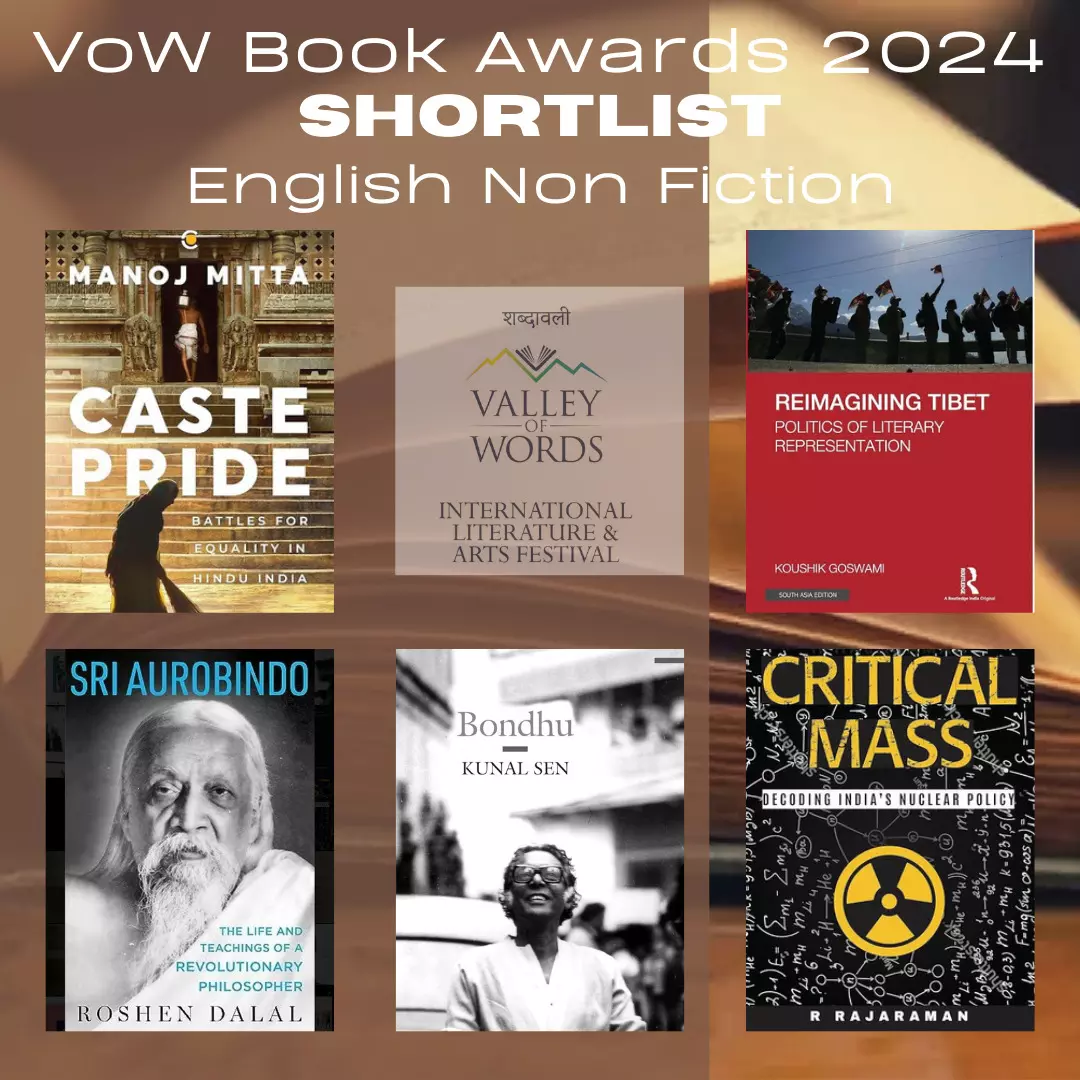

This year's shortlist, curated by Ishtiaq Ahmed, features five seminal books, of which two are biographies of very distinguished individuals — the spiritual savant Sri Aurobindo, whom Roshen Dalal calls 'a revolutionary philosopher', and 'Bondhu', a touching tribute to his father, Mrinal Sen, by his son Kunal. Bondhu is a term of endearment for an intimate friend. Both also give us the flavour of Bengal, though the anglicised world of Sri Aurobindo was as different from that of the refugee family of Mrinal Sen. In today's column, we will take up both of these.

Aurobindo Ghose nearly made it to the heaven-born ICS, but as 'his heart had its reasons', he deliberately skipped the riding test to earn a disqualification, for his written marks had earned him a place on the merit list. Returning to India at the age of twenty-one, he joined the equivalent of the Baroda state civil services, became the speech writer to His Highness, the Maharaja, who liked his flair and passion for writing. This was more suited for an academic rather than an administrative position, and he was sent to Baroda College. Polyglot he already was, with fluency in English, French, Latin, and German, he now picked up Sanskrit, Bangla, Marathi, and Gujarati — making him one of the most well-read men of his times in the country. Like many of his compatriots, he joined the Congress party, but was not exactly aligned to the 'gradualist, constitutional approach' and preferred the path of the revolutionary Anushilan Samiti. He was then closely aligned with Bande Mataram, the paper started by Bipin Chandra Pal — one of the trinity of Bal, Pal, Lal (Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal and Lala Lajpat Rai). A year in solitary confinement in the Presidency Jail transformed his life — he had visions of the Divine, and decided to quit politics to become a spiritual seeker, expounding his views on Integral Yoga for a new world order.

Let us now look at the way Dalal brings her muse to life for the contemporary reader based on three decades of painstaking research as an accomplished historian. The book deftly depicts his teaching alongside the biography, making the book a learning experience for the readers and researchers alike. The first chapter discusses Aurobindo's life before coming to Pondicherry. His Anglophile father sent him to England, where he studied, and after his return to his beloved Bharat, he worked in Baroda, which was great but not challenging enough. Then comes the short revolutionary phase of his life. Surprisingly, Aurobindo's Uttarpara speech, where he equated Sanatan Dharma with nationalism, does not find a reference.

The second chapter discusses his life after coming to Pondicherry and how he made a group of his disciples including his spiritual companion, the Mother. The third chapter explains his analysis of ancient texts like Veda, Bhagavad Gita, and many more. In the fourth, he elaborates on the references to terms like cows, horses, fire, etc. — they had a deeper mystic connection with the Vedic rituals. The fifth chapter delves into the competing philosophical discourses within the overarching umbrella of the Hindu belief systems: Advaita, Shakta, Tantra, but also examines his thoughts on Western philosophies. The next three chapters talk about his perennial works like Savitri, A Life Divine, Synthesis of Yoga. A Life Divine talks about human, nature, overmind, supermind, etc. Then we have a chapter explaining that Yoga is not twisting and turning the body, but is a union with specifically the Divine. ‘Savitri’ is a literal and metaphorical offering — a conversation between life and death, with a deep mystic meaning. The last chapter explains the life of the Mother aka Mirra Alfassa, for while Aurobindo conceptualised the Ashram, it was The Mother who planned everything to the last detail.

The next offering is a biography of Mrinal Sen by his equally accomplished son, Kunal, published on the occasion of his birth centenary in 2023. Like the people he grew up with, Kunal is a great raconteur, as well as a person of deep reflection. Bondhu takes us on an intimate journey of a son attempting to reconcile his father's public and private selves. Growing up in a middle-class household in South Calcutta, where his father's Marxist beliefs and unrelenting urge 'to be challenged and contradicted' often collided with the practical challenges of making a living. And through it all, the family's unyielding commitment to the craft of cinema, the risks they took, and their endearing sense of humour comes to the fore. He recalls how his father took him to a tram station terminal to play a game of hide and seek - much as two friends would do if they were together. Perhaps this was the moment when his father also became his friend - and that tie remained till the very end.

"No one remembers when and why I started calling my father Bondhu. It was a strange way to address a father, as the word means ‘friend’ in Bengali. . . . As I got older, I became very self-conscious about such an odd name . . . and yet I cannot explain why I could not switch to the more acceptable Baba or something similar.”

This unputdownable book is divided into three parts: Bondhu, Filmmaker, and Father. But it is as much a tribute to his remarkable mother, Geeta Sen. “It is impossible to understand my father without the story of my mother, and it is impossible to understand my mother without the story of her trials and tribulations as a young teenager”, Kunal writes. His mother was just fifteen, but the eldest sibling – with two younger sisters and a brother when she assumed the task of running her family as her father was critically ill. As she experienced poverty first hand, there was no ‘romance’ in it, but the positive aspect was that it helped her to adjust to her husband’s entirely casual financial approach towards running the family. For several years, she was a homemaker, till both her husband and son persuaded her to face the camera, and she gave memorable performances in films like Calcutta (1971), Chorus (1974), Ekdin Pratidin (1979), Aakaler Sandhaney (1980), Chaalchitra (1981), Kharij (1982), and Khandahar (1983). After that stint, though, she stepped back once more and nothing could make her return to the screen or even the stage. Bondhu comes across as a truthful, emotional tribute by a son to his father that offers glimpses of an unusual father-son relationship. Unlike the sons of most other filmmakers in India, Kunal Sen never became a filmmaker. Though an air of nostalgia permeates his recollections of being on the sets of his father’s films, Kunal’s forte was data, data, and more data, leading him to study first at the ISI, and then to the USA for higher studies in AI.

My favourite part of the book is the passage on Eklavya’s thumb, and the ruckus created by a tribal boy in Purulia when Mithun Chakrabarty draws the string of the arrow with his thumb. Mrinal was unhappy and annoyed with the fact that the shooting had to be stopped abruptly, but he learnt that this was because for millennia, tribals had stopped using their thumb in archery when Eklavya was forbidden to do so by Dronacharya. Mrinal Sen had mentioned that this was indeed a moment of epiphany for him, as it was for me when I read this particular passage.

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature