Between the Two Worlds

India and China, despite their shared historical dominance in the global economy of yore, have taken divergent paths. While China banks on self-reliance, India remains dependent on external technology and imports, particularly from China, leading to economic vulnerabilities

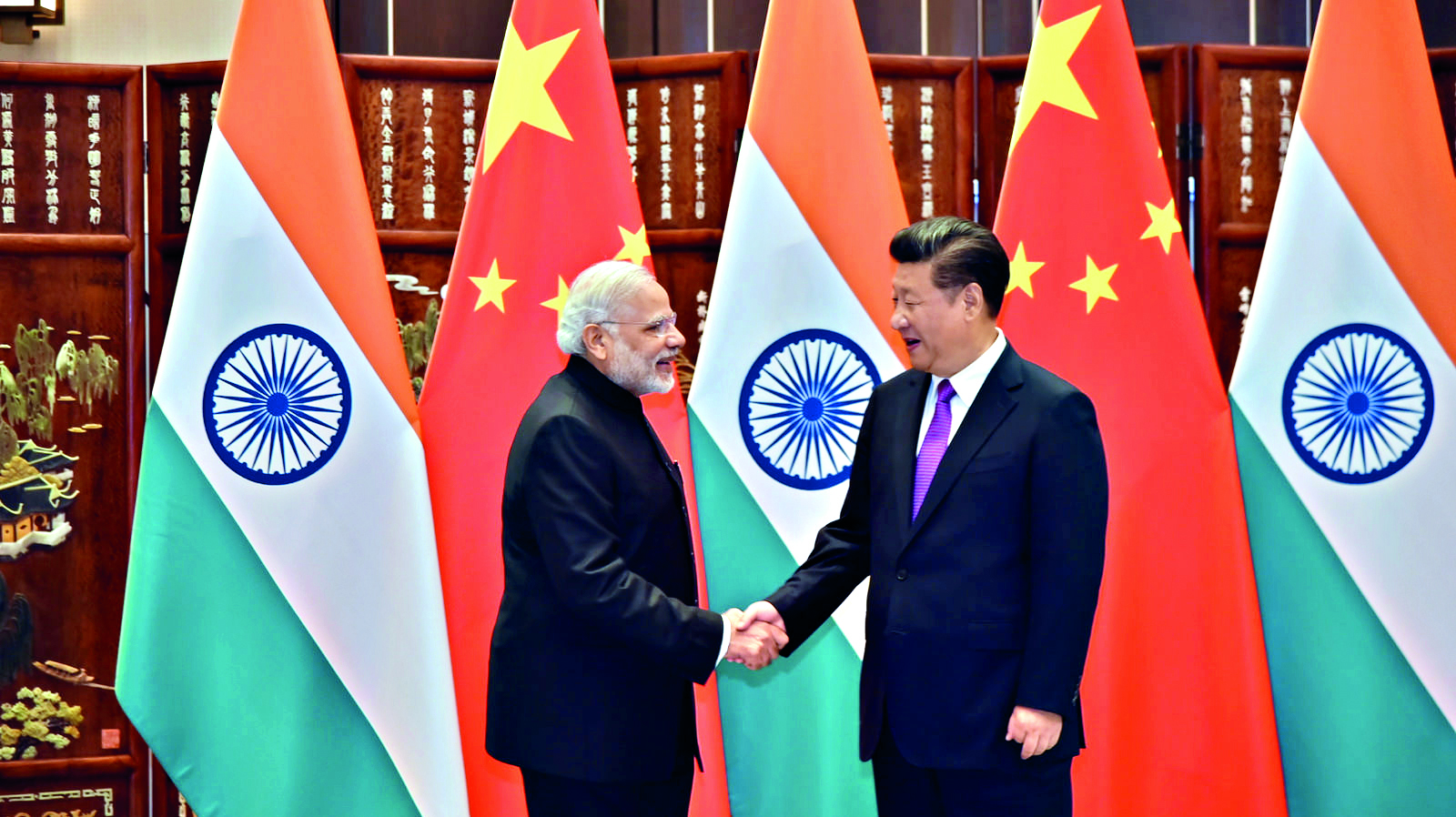

India and China, two of the world’s oldest civilisations, stand at a crossroads of history, with their shared rich cultural heritage and complex relationship shaping the modern world. On October 30, 2024, H.E. Mr Xu Fei Hong, China’s Ambassador to India, published an article, titled ‘The elephant, dragon tango’ in The Indian Express, elaborating on China’s economy. In his piece, the Chinese ambassador reiterated that development was the biggest shared goal of China and India. China has put forward the goal to build itself into a great modern socialist country in all respects through the middle of this century. India also has the vision of ‘Viksit Bharat 2047’. The contribution to each other’s success would create huge development dividends and strategic opportunities, he wrote.

However, amid the rising concerns over potential export disruptions due to US reciprocal tariffs, set to take effect on April 2,2025, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry has asked Indian businesses to identify areas where imports from China and other countries can be substituted with American goods.

On April 1, 1950, India became the first non-socialist bloc country to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) which was founded on October 1, 1949 — two years after India attained independence in August 1947. This journey is remarkable because of periods of both cooperation and conflict, including the 1962 Sino-Indian War, and efforts towards normalisation and increased trade.

In 2023-24, China emerged as the largest trading partner of India with USD 118.4 billion two-way commerce, slightly edging past the USA. The bilateral trade between India and the US stood at USD 118.3 billion in 2023-24. India’s exports to China rose by 8.7 per cent to USD 16.67 billion, and Imports from the neighbouring country increased by 3.24 per cent to USD 101.7 billion. Nonetheless, in the emerging trade war between China and the USA, India has openly sided with the USA.

India & China: Global Leaders During 1-1820 AD

Angus Maddison (1926-2010), a world scholar on quantitative macroeconomic history, estimated the GDP of China and India — among other nations — since the first Millennium. Table 1, compiled from different writings of Maddison, shows the share of India’s and China’s GDP to the global GDP between AD 1 and 1998. The table indicates that till 1500 AD, India and China contributed nearly half of the total GDP of the World. During the 1st Millennium, these two Asian economies contributed more than half of the global GDP. Their combined share declined to nearly fifty per cent of the global GDP in the first half of the 2nd Millennium (1000-1500 AD). Up to the middle of the 2nd Millennium, India’s GDP share was higher than that of China.

From 1500 AD, China started to grow faster than India and dominated the world economy up to 1820 AD, when the Industrial revolution was evolving in Western Europe. In that year China maintained 33 per cent share in the global GDP. By then, India’s share declined to 16 per cent, though the combined share of China and India remained close to half of the global GDP. After that, the decline started and, in 1950, after a long period of suppression by colonial powers, their respective shares in the global economy fell to 4.5 per cent and 4.2 per cent, respectively. Their combined share declined to as low as 8.7 per cent from a high of 49 per cent in 1820. By the end of the 2nd Millennium, the combined share of India and China’s GDP in the global GDP was less than 20 per cent, though at the beginning of the 1st Millennium, the combined share was 59 per cent.

75 Years of Diplomatic Journey

This year marks the 75 years of diplomatic relations between India and China—world’s two most populous nations. Although the border conflict of 1962 was a setback to bilateral ties, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s 1988 visit marked a beginning in the improvement of bilateral relations.

In recent years, the economic rise of China has led to suggestions of a ‘Beijing Consensus’ as an alternative model of development to the ‘Washington Consensus’. At present, the United States of America is the world’s largest economy. As per IMF’s projection, in 2024, USA’s nominal GDP was USD 29,840 billion. It was followed by China with USD 18,533 billion GDP. Germany ranked third with USD 4,772 billion, and India is considered as the fourth-largest economy with a GDP of USD 4,340 billion. China’s economy is more than 4.27 times of the Indian economy.

Table 2 shows, during 1960-70, India’s per capita GDP was marginally lower than China. Then during 1970-90, India’s per capita GDP was significantly higher than China’s per capita GDP. When Rajiv Gandhi met Deng in 1988, India’s per capita income was higher than China’s per capita income. It appears that after the opening up of India’s economy in the early 1990s through liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation (LPG), India failed to keep pace with China’s economic growth. Between 1990 and 2000, China’s per capita income, compared to India, more than doubled and, in 2023, it was five times more than India’s per capita income.

During the last few decades, China has surpassed India in almost all socio economic parameters. In 1978, China’s Human Development Index had put China squarely in the ranks of low human development countries. By 2018, China’s HDI had reached 0.752, making China a ‘high human development country’ as per UNDP’s classification criteria. Compared to China, India’s HDI value reached 0.644 in 2022, placing the country in the ‘medium human development category’. In the 2023-2024 Human Development Report, India ranked 134th out of 193 countries and territories, while China ranked 75th.

Banking on Different Development Models

China has never deviated from Mao’s philosophy of self-reliance. While self-reliance was championed by Mao, it has been supported by all subsequent leaders, including Xi, even if its application has evolved over time. Self-reliance was borne out of wartime necessity. Mao proclaimed the virtues of self-reliance as early as January 1945, when the CCP was forced to operate out of the remote Shaan-Gan-Ning border region while fighting both Japanese invaders and nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-Shek. Anxious to assert his patriotic credentials in the Chinese Civil War, Mao framed the CCP’s self-reliance as “the very opposite” of Chiang’s dependence on US military aid. The success of the First Five-Year Plan (1953-1957) helped convince Mao that China could grow faster by returning to its revolutionary roots and giving “primary importance” to self-reliance. Between 1958 and 1978, the CCP “vigorously propagandised” self-reliance, especially following the Sino-Soviet Split in the early 1960s and during the Great Leap Forward (1958-1960), the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), and the heyday of the Third Front campaign (1964-1971).

Mengna Luan and Tuan-Hwee Sng (2020), investigated whether local communist party membership affected China’s developmental outcomes between 1957-78 (the Maoist period) and 1978–85 (the reform period). Their study revealed that counties with more communist members made larger strides in educational attainment, road construction, and agricultural mechanisation during the Maoist period. However, these counties recorded faster output growth only after 1978. The findings provided empirical support to field studies conducted by sociologists and historians who had argued that the communists improved the organisational infrastructure in China’s countryside. The thrust on self-reliance prompted China to build its successful development strategy on the twin pillars of human capital and gender equality, areas in which India has lagged far behind.

Unlike China, India followed a different model of development relying on borrowed technology and capital. Dey D (2019) argued that since 1947, independent India has been incorporated by the larger global system, reinforcing a colonial legacy. Post-colonial India has followed the same model of economic growth with a centralised production system in few power centres of North, West and Southern India at the expense of other zones. The new rulers have applied the ‘infrastructure of dependency’ model, the functional equivalent of a formal colonial apparatus, to treat various non-Aryan races and peripheral regions as the ‘internal colonies’ of the Brahmanical state. Internal colonialism refers to the subordination of an ethno-racial group in its own homeland within the boundaries of a larger state dominated by a different people.

India’s Increasing Dependence on China

A study of China’s growing trade surplus underlines a shift by the PRC away from the US and EU to the Global South. Between 2013 and 2023, China’s trade surpluses were hinged less on developed economies and more on developing countries, unlike what was the case a decade ago. Southeast Asian economies and India, for instance, had witnessed a threefold rise in trade balance with China between 2013 and 2023, compared with a 1.5 times increase for the US and a 2.5 times increase for the EU. The US accounted for 83 per cent of China’s trade surplus in 2013; the North American nation had a 40.8 per cent share a decade later. India’s share of the trade deficit with China increased from 1.6 per cent to 2.8 per cent of GDP during 2013-2023.

During 2023, India ran a trade deficit of USD 84 billion with China, which rose to USD 94 billion in 2024, whereas its trade surplus with the US extended from USD 31 billion to USD 36 billion in 2024. Even as India tries to placate Trump over high tariffs, it would still not be able to bridge the trade deficit by substituting Chinese imports with those from American goods, as it would come at a higher cost. In fertilisers alone, the cost build up for India could be a high USD 223.8 million if it buys the same product from the US.

Media reports suggest that the Modi government is focusing on a proposed Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) with the United States rather than engaging in talks over reciprocal tariffs. To finalise the shape of the proposed bilateral-trade agreement (BTA), a team of United States (US) officials, headed by Assistant Trade Repres¬entative Brendan Lynch, will come to New Delhi next week to hold discussions with their counterparts here.

Though the Indian Ministry of Commerce and Industry has asked businesses to identify areas where imports from China and other countries can be substituted with American products, analysis shows that the value of trade in India that can be substituted with American goods is likely to be limited. Out of the 4,251 imported goods where comparable data was available from the Ministry of Commerce, the US had a price advantage in only 650 items while China’s price advantage extended to 3,601 goods. India will only be able to shift USD 3.5-5 billion of trade away from its largest trading partner — China — and replace it with goods imported from the United States, reports MoneyControl.

Over the years, all the major sectors of the Indian manufacturing industry have become dependent on Chinese imports. In 2023-24, the top eight Chinese products imported to India were: (i) electronics & telecommunication, (ii) machinery, nuclear reactors, boilers, (iii) organic chemicals, (iv) plastics, (v) optical photo, technical, and medical apparatus, (vi) iron & steel, (vii) fertilisers, (viii) vehicles (excluding railway or tramway).

The reliance on China for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) has been a mounting concern for the Indian pharmaceutical industry. India is heavily dependent on China for imports of raw materials, Key Starting Materials (KSMs), and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). India is the source of around 60,000 generic brands across 60 therapeutic categories and manufactures more than 500 different APIs. However, India imports about 70 per cent of its APIs from China as it’s a cheaper option than manufacturing them domestically. In 2023-24, India imported APIs and bulk drugs worth Rs 377 billion, accounting for 35 per cent of its total API requirement, of which China accounted for 70 per cent. Moreover, dependence on Chinese imports of APIs for certain essential medicines is as high as 80-100 per cent. Almost the entire requirement of certain fermentation-based APIs like ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin is sourced from China. The cost advantages with the Chinese API industry and the volatility in the prices of APIs have made domestic production of certain APIs unviable for Indian manufacturers, resulting in continued dependence on China. Even where APIs are manufactured locally, KSMs are primarily sourced from China. It is alleged that the competitive pricing offered by Chinese suppliers has significantly influenced this dependence. Over the last few decades, the percentage of API imports from China has surged dramatically—from a mere 1 per cent in 1991 to an astonishing 70 per cent in 2019.

Observations

It appears that a few young leaders of India have ultimately realised that R&D should be the primary focus, and expenditure in research should be increased to minimum 1.5-2 per cent of GDP from its current spending of 0.6 per cent of GDP. Suddenly, there is a call for “Manhattan Project for Indian science and tech” as India now “heavily depends on the US and China for cutting-edge technologies like AI, GPUs, semiconductors, quantum computing, biotech, and new blockbuster drugs.”

In a significant confession, another young business leader has observed that India’s economic rise has been fuelled by its booming IT sector, driving exports, employment, and innovation, but this overreliance on technology services has raised concerns about economic resilience, with shifts in global demand or financial disruptions posing potential risks. Comparing financial bubbles to “flash floods,” he explained, “When money pours into an industry too rapidly, it sucks resources and can leave us with fewer capabilities than before in other critical sectors that get neglected during the flood of money.” He further argued that the dominance of IT has “sucked all the oxygen” from the economy, leaving industries like manufacturing and core engineering struggling for attention and investment.” It needs to be mentioned that during the last four decades, when China consolidated its economy and emerged as the global leader in science and technology, India suffered from ‘Dutch disease syndrome’ due to the dominance of the IT sector led by a few Dot Compradors of India. It refers to the economic phenomenon where a boom in a specific sector leads to a decline in other sectors, like manufacturing. The term “Dutch disease” emerged in the 1970s to describe the economic consequences of the Netherlands’ natural gas boom on its manufacturing sector which reduced overall economic growth.

There is a basic difference in the political culture among ruling establishments of China and India. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sees history not as a record, still less a debate, but a tool. For the CCP, engaging with history is not necessarily about the past, but a purposeful political endeavour to shape future direction. India’s former diplomat Shyam Saran argues that this instrumental approach to history has been a hallmark of Chinese political life. Unlike CCP, the Indian political establishments have remained engaged in searching for a national identity on the basis of Hindu mythology. Regrettably, mythology, not history, dominates modern India’s political discourse.

Views expressed are personal