This Haircut Can Kill

Snipping away at unkempt hair and sniping at thousands of crores in bad loans are vastly different. Get either wrong, though, and you will have a bad hair day

“If you owe ten pounds to

the Bank of England, you

get thrown in jail. But if

you owe a million pounds,

they put you on the Board.”

—Philippe Riès

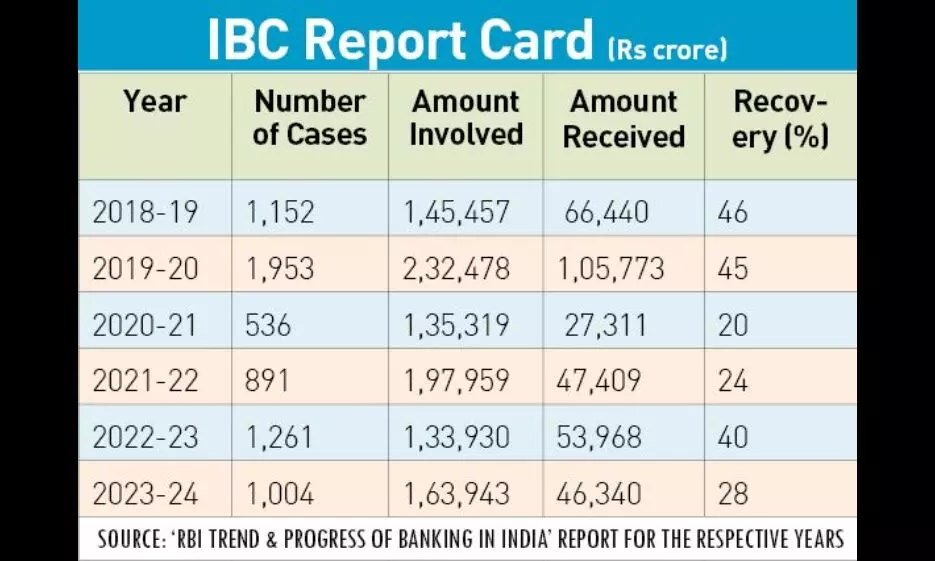

A headline or two (and more) in newspapers last week caught my eye, leaving me bemused. ‘IBC cases dip in India’, they celebrated. These expert number-crunchers and line-toeing conformists were, of course, being subservient to their masters while reporting on unpaid loans (or bank NPAs/bad debt). They were somewhat right; the number of cases filed in FY 2023-24 had indeed dipped over FY 2022-23, by 257 to be precise. They were wrong too; for they mysteriously failed to mention that actual recoveries had also fallen—by 12 per cent in a year, or by Rs 37,551 crore in percentile value terms YoY.

Bankers call post-resolution unrecovered debt a ‘haircut’. Haircut indeed. Typically, this involves snipping away at a head of unkempt hair. Sniping at thousands of crores in bad loans is a bit different. The only common thread is that when the process goes wrong, people have a really bad hair

day. I can but laugh mirthlessly at my brethren in the media who call this development a ‘revival’ and other saintly words. They are failing to tell you that when large Corporates default, they set in motion a chain reaction—with the zipper being pulled down belonging to you and me. That takes us to 2023. Banking danger bells pealed in the US, with reverberations being felt in India.

Two top banks—Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank—almost downed shutters, leaving India and the rest of the world worried. The Reserve Bank of India issued warnings to banks, advising a hawk-eye scrutiny of balance sheets and NPA figures.

The saving grace was that India, by that time, had already weathered the Yes Bank and Punjab & Maharashtra Cooperative Bank scares. At that time, forewarned was forearmed. But we might not always be so fortunate.

‘One-Eyed King’ Wins

Back to the issue at hand, reports from rating agencies and analysts affirm that the number of new cases filed under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) is declining, indicating that banks are looking at alternative methods of debt recovery, instead of insolvency proceedings. “This is due to factors like delays in the IBC process and a need to maintain relationships with borrowers,” one agency said. (For the life of me, though, I can’t fathom why any ethical banker would want to maintain such a relationship in the first place).

Since its inception in 2016, IBC has seen most cases witness sharp haircuts for creditors, apart from long recovery time-frames. The reason to still walk this route is that IBC has been better for banks than options like debt recovery tribunals and bodies overseeing the reconstruction of financial assets and enforcement. For some reason, analysts do not state that recovery rates are dipping too. For instance, recovery slid to 28 per cent of outstandings through FY24, with resolution timelines getting stretched to breaking point. Dig deeper and we get to cumulative recovery rates, which have also witnessed a downtrend, from 43 per cent in Q1FY20 and 32.06 per cent in Q1FY25. A reason is larger resolutions have already happened and most firms were either referred under BIFR (the erstwhile Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction) or are now defunct due to high-resolution timelines. The time taken for resolution or liquidation has been rising exponentially.

IBC After COVID-19

After slowing down during the pandemic of FY21 and FY22, cases referred to IBC increased by 13 per cent YoY in Q2FY25. However, despite this rise, the number admitted for insolvency were lower compared to the earlier quarters of FY20. Today, the number of ongoing Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) cases is hovering at around 2,000, with ‘manufacturing’ accounting for the largest number of defaults.

The delays for CIRP closure are high compared to ‘Liquidation’ across categories, but corporate debtors do seem to take less time for resolution compared to financial and operational creditors. Sequentially, the number of days for resolution and case closure has increased across categories.

Look at the 2,000 ongoing CIRPs. As many as 71 per cent could not meet the ‘270 days’ deadline for completion of the process in September 2024, compared to 63 per cent in September 2022 and 67 per cent in September 2023. The share has moved to the higher tier. If we look at the

‘Less Than 90 Days’ segment from the resolution standpoint, it is the smallest. This underscores the fact that while new cases are being added and earlier cases are chugging along, they are delayed for myriad reasons.

The final nails in the resolution coffin—one, the share of the ‘More Than 90 Days, But Less Than 180 Days’ and ‘More Than 180 Days, But Less Than 270 Days’ segments has reduced; and two, 55 per cent of cases have been pending for ‘More Than Two Years’, and 21 per cent for ‘Over One Year, But Less Than Two Years’. Clearly, resolution takes a while, and then some. But my expert media brethren are not writing about this at all.

Wilful Defaulters Galore

The last released list of wilful defaulters also presents an alarming trend. I will not name individual banks and numbers, but here’s a bird’s eye view—the number of wilful defaulters was last pegged at 15,778. These are big-ticket, high-figure loans given to those who can afford to return the money but do not, and hence their well-earned ‘wilful defaulter’ status. Some argue defaulters have always existed in the banking system globally.

True. But prior to COVID, their number in India was around 10,000. In the last four years, their ranks have swelled by over 50 per cent.

Two years back, the top 50 wilful defaulters in India owed Rs 92,570 crore to banks. Add in others who are (hopefully) ‘not wilful’ and you arrive at a figure close to around Rs 20 lakh crore. There’s a saving grace here too, in that public sector banks have recovered around Rs 6 lakh crore, including over Rs 1 lakh crore from written-off loans over the last five financial years.

Then we have the gnawing and worsening scenario of growing disparity, with the rich getting richer and the have-nots sliding further down the value chain. Therein lies the reason that luxury items, cars and goodies are seeing a jump in sales, while daily essentials such as mixer-grinders, gas cylinders, scooters, cycles and even undergarments being slipped off. In a country where 81 crore people are provided free rations, sales of ultra-swank luxury cars are up 32 per cent. On the flip-side, sales of scooters and motorcycles are declining.

Net-net, you or I take a loan to buy something, we repay it or the goods get re-possessed (while we get de-possessed). The rich are different. If they take a loan and fail to repay, they go to London or Antigua or some similarly exotic destination.

This is leading to restlessness and unrest, in the financial, social, societal and communal front(s). Dennis Lehane gets macabre while summing up this grimness: “People were lost and scared. Their lynch ropes couldn’t reach bankers or stockbrokers, so they looked for targets closer home.” Sounds familiar? If it does, it is time my brethren the experts to start writing about the real stuff.

It is only after we accept and confront reality that we will learn to deal with it.

The writer is a veteran journalist and communications specialist. He can be reached on [email protected]. Views expressed are personal