Law. Justice. Overreach.

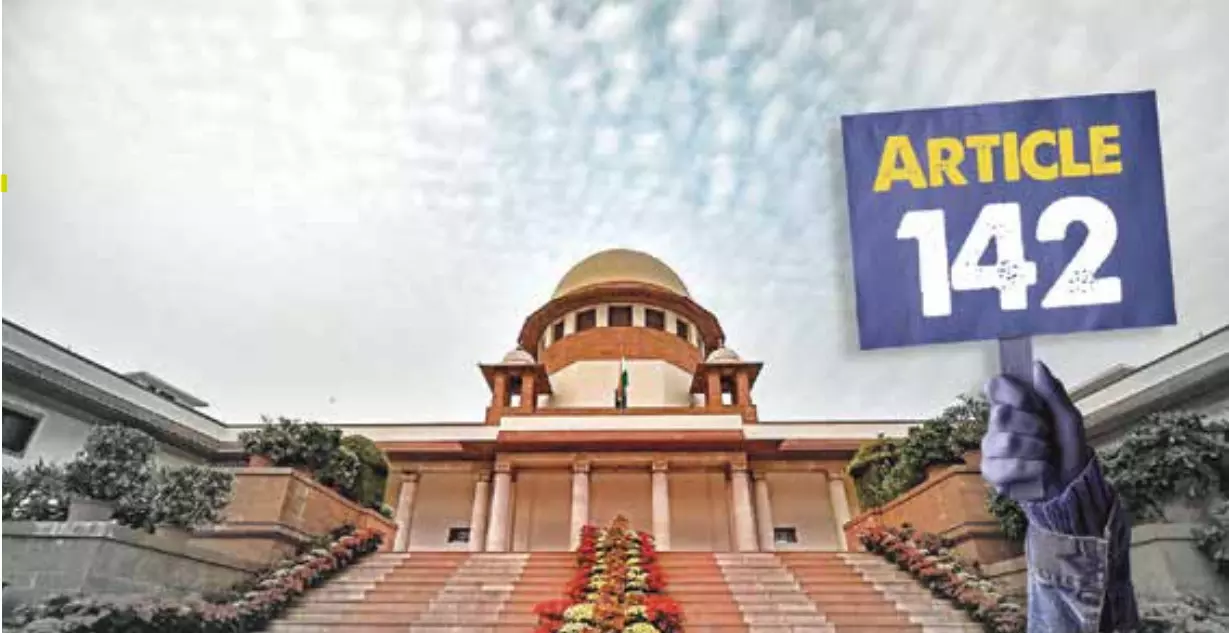

Instances of the Supreme Court leveraging Article 142 to deliver ‘complete justice’ posit concerns around its undefined scope and fading balance between the judiciary and the legislative

Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar recently referred to Article 142 as a “nuclear missile against democratic forces,” expressing concerns about its potential for judicial overreach. His statement has fuelled the ongoing debate over the expanding role of the judiciary in matters traditionally handled by the executive and legislature.

In the landmark judgement of The State Of Tamil Nadu vs. The Governor Of Tamil Nadu & Anr., the Supreme Court imposed a one-month deadline for Governors to act on bills passed by state assemblies and a three-month deadline for the President to act on bills reserved for consideration. The Court ruled that the President’s decision to withhold assent on bills reserved for consideration can be challenged on grounds of ‘arbitrariness or mala fides’. Prolonged inaction by the President also allows the State to seek a writ of mandamus.

However, this ruling introduces subjectivity in reviewing the President’s decisions, particularly in determining whether an action is ‘arbitrary or malafide,’ terms that lack a clear legal definition and may lead to inconsistent judicial intervention. Moreover, granting ‘deemed assent’ to the bills undermines the Governor’s discretionary powers by presuming “lack of bona fides” on his part without clear evidence. This approach risks disrupting India’s delicate separation of powers.

While the Supreme Court swiftly interprets ambiguous constitutional provisions, it has time and again avoided giving a clear, objective definition of Article 142 and ‘complete justice.’

Article 142 and ‘Complete Justice’

Article 142 empowers the Supreme Court to pass any order or decree necessary to ensure complete justice in matters before it. These orders are enforceable across India and until Parliament frames a law for enforcement, the President may prescribe the procedure. No other constitution grants such powers to its courts, except Bangladesh and Nepal, both inspired by the Indian model. While invoking Article 142 to fill legal gaps is justified, using it to override existing laws crosses the line into abuse of power and judicial overreach.

Explaining the scope of this power, in Supreme Court Bar Association v. Union of India (SCBA), Justice AS Anand, clarified that “Article 142 cannot be used to build a new edifice where none existed earlier, by ignoring express statutory provisions dealing with a subject and thereby to achieve something indirectly which cannot be achieved directly”. The powers under Article 142 of the Constitution were held to be ‘supplementary’ in nature and not those which could be used to ‘supplant’ the applicable legislation.

However, several instances suggest that the Court has at times used this provision to override substantive laws, such as in State of Tamil Nadu v. K Balu, where the Court banned liquor sales within 500 meters of national highways using its powers under Article 142, disregarding state excise laws. This was criticised for lacking balance and consideration of regional differences. Similarly, the Court has used Article 142 to direct the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to investigate crimes in states without their consent, bypassing the statutory requirement under Section 6 of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946. While these actions are often justified by the court as necessary for ensuring justice, they raise concerns about the erosion of state autonomy and the proper limits of judicial power.

A Double-Edged Sword

Judicial activism can play a crucial role in protecting fundamental rights and addressing governance failures, especially when elected representatives fall short. However, when it overrides statutory law, it risks undermining the democratic process. Laws should reflect the will of the people, and when judges replace the legislature’s decisions, it can lead to constitutional chaos.

When the Supreme Court of India had the opportunity to explain the meaning of ‘complete justice’ in Delhi Development Authority v Skipper Construction Co. it stated “As a matter of fact, we think it advisable to leave this power undefined and uncatalogued so that it remains elastic enough to be moulded to suit the given situation. The very fact that this power is conferred only upon this Court, and on no one else, is itself an assurance that it will be used with due restraint and circumspection”. The Court’s rationale that leaving power undefined ensures flexibility, conveniently overlooks the risks of subjective interpretation, paving the way for judicial overreach.

It’s important to note that when the Constitution was drafted, Article 142 was passed without debate, leaving it open to wide interpretations. Every time the Court stretches beyond the law, it inches closer to encroaching on the legislature’s domain. The Court needs to strike a balance between delivering absolute justice and respecting the constitutional roles of elected representatives. In its chase of ‘complete justice’, the Court has to be cautious not to disturb the very democratic balance it is meant to safeguard.

The writer is a senior law student at Panjab University, Chandigarh and a commenter on legal matters. Views expressed are personal