Fading Footprints

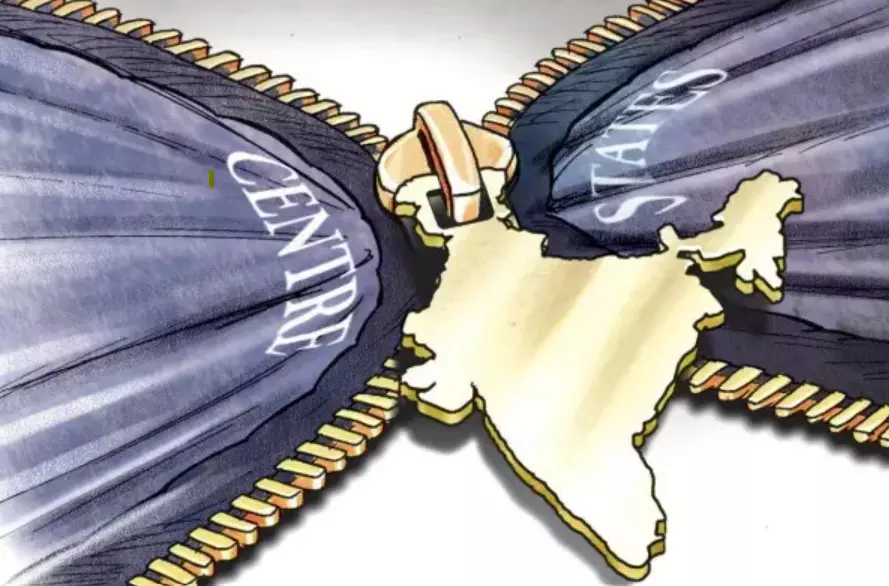

With the central government increasingly vying for re-centralisation of powers, the vital concept of cooperative federalism is gradually losing its grip over Indian polity

Federalism is a pragmatic creation of human ingenuity, designed to balance power and promote democratic governance. Characterised by a constitutional division of powers between at least two levels of government, federalism accommodates diverse identities and interests through a system of territorial representation. This framework is further reinforced by the separation of powers and an independent judiciary, with the Supreme Court serving as a neutral arbiter in disputes between different levels of government. By dividing sovereignty and providing a degree of autonomy to minorities, federalism safeguards against the tyranny of the majority, thereby fostering a more inclusive and democratic polity.

Indian federalism bears the imprint of its colonial past, as embodied in the Government of India Act 1935. The country's federal structure was also shaped by the lessons learned from the traumatic experience of partition on the eve of Independence, as well as the need to accommodate its multicultural diversity. While India adopted a dual polity, the Constitution's architects deliberately avoided using the term 'federal' in the final document, although it was frequently used in the draft Constitution. Instead, India was characterised as a 'union of states' carrying quasi-federal character but conveying a higher degree of integration. The nation witnessed significant territorial reorganisation in the 1950s to accommodate demands from linguistic and ethnic minorities. The breakdown of the Congress party's dominance in the late 1960s led to the rise of regional political parties, which began to assert their influence in various states. A notable example is the DMK government in Tamil Nadu, which appointed the Rajamannar Committee to push for greater state autonomy. The transformation of India's governance from a single dominant party system to a multiparty system in the 1960s significantly bolstered the country's federal structure and introduced more diverse perspectives and interests into the political arena. This shift allowed for greater political and economic decentralisation, enabling power to devolve away from Delhi and towards regional authorities.

The emergence of coalition governments at the Centre heralded a new beginning in Indian federal polity, introducing a new era of cooperation and negotiation between national and regional parties. This development was characterised by parties in power at the state level extending external support to the coalition government, thereby minimising centre-state conflicts and making them more resolvable. A remarkable example of this shift is the United Front Government which emphasised the devolution of greater economic and administrative autonomy to the states, setting the tone for a more decentralised federal polity.

The regionalisation of the party system in the 1990s and 2000s led to a process of federalisation, where states gained greater political and economic autonomy. However, this also created an environment where Hindu majoritarianism could rise at the national level, unchecked by the federal system. The central government's attempts to undermine federalism have been a major concern. For instance, Parliament has used provisions in Articles 249 and 250 to take away powers from states and add them to the Concurrent or Union Lists. Added to it is the frequent deployment of Central forces in states during law and order crises, despite law and order being a state matter. Instances of the Centre misusing this provision to serve its own interests have undermined the spirit of cooperative federalism. This has led to an imbalance in the already skewed distribution of powers. The growing weakness in institutionalising states' roles in national legislation and policy-making, coupled with globalisation directives, has facilitated a shift towards national federalism, where choices are dictated rather than negotiated. The BJP-led coalition government at the Centre has posed new threats to India's federalisation process.

At its core lies the Hindu nationalist concept of Indian nationhood. This trend has gained momentum with the creation of new institutions like NITI Aayog and the Goods and Services Tax Council. Recently, the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) and the central government have experienced a significant rise in influence and importance. The Modi government's stance on federalism appears to be a case of "do as I say, not as I do."

The passage of the Delhi Services Bill is a prime example of this. By empowering Parliament to make laws for services in Delhi, the central government is effectively diluting the powers of the Chief Minister. Similarly, the National Education Policy has been met with strong reservations from some states that see it as an attempt to centralise authority and undermine their autonomy. The creation of bodies like the National Education Commission, Academic Bank Credit, and Common University Entrance Test only reinforces this perception. More recently, Tamil Nadu's opposition to the three-language formula has sparked a confrontation with the central government, which has threatened to withhold funds.

The GST Council, initially envisioned as a beacon of fiscal federalism, has become a contentious issue. With the Centre holding one-third of the voting rights, states' voices are being muted. While there have been increased transfers to states, this has come at the cost of reduced funding for centrally sponsored schemes. The situation worsened when the Centre stopped providing compensation to states for revenue losses due to GST implementation, which was initially guaranteed for the first five years. This calls for revisiting the framework of GST by re-examining the taxation powers listed in the Seventh Schedule and exploring ways to enhance states' fiscal autonomy.

Despite a clear division of powers between the Centre and states, fiscal transfers can be influenced by states' bargaining powers, further undermining their autonomy. The Finance Commission, intended to balance the federal system, has faced challenges in addressing states' grievances and encouraging better financial performance.

The revocation of Jammu and Kashmir's special status under Article 370 during the pendency of the President’s Rule is another significant example of the central government's disregard for cooperative federalism.

Again, on August 5, 2019, the Indian government issued a presidential order superseding the 1954 order that granted special status to the state, enabling it to have a constitution, flag, and autonomy over internal administration. This move was followed by the passage of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, which bifurcated the state into two union territories. The apex court has upheld the government’s decision but the controversy remains.

Regulatory bodies, such as the Central Bureau of Investigation and the Central Vigilance Commission, are often subjected to central pressures and influence, undermining their independence. The changed mode of appointment of the Chief Election Commissioner has sparked concerns among opposition parties, who fear that the central government is attempting to exert control over the electoral process and thus to undermine democracy . These developments have eroded trust in the central government's commitment to cooperative federalism, transcending partisanship and thus raising questions about the future of India's federal structure. Reviving the National Development Council can provide a platform for states to raise their concerns and participate in national development processes. Revitalising the Inter-State Council, enhancing financial transparency, and promoting cooperative federalism are crucial steps in this direction. Furthermore, striking a balance between centralisation and decentralisation is essential to protect democracy and ensure balanced development. Additionally, fostering inclusive and participatory governance processes that involve all stakeholders, including states, civil society, and citizens, is essential for promoting cooperative federalism and achieving the vision of Vikashit Bharat and Sabka Sath, Sabka Vikas. Decentralisation is sine qua non of this vision.

The desire to build a Hindu nation may lead to a homogenisation of cultures, undermining India's multicultural heritage. The federal system was designed to protect and promote diversity and integration, but re-centralisation and majoritarianism may erode their pillars and the democratic structure of India. More bridge-building initiatives at the instance of the centre to promote trust between two sets of government followed by transparent revenue—sharing and timely GST compensation—seem to be the need of the hour.

Fr. John Felix Raj is the Vice Chancellor of St. Xavier’s University, Kolkata and Prabhat Kumar Datta is the Adjunct Professor of Political Science and Public Administration at Xavier Law School, St. Xavier’s University, Kolkata. Views expressed are personal