Bibek’s Personal Obituary

It was reflective of life. It spoke of death. It mentioned the in-between. It was realistic. It was platonic. It was also the first time I read an obituary before it appeared in print, and it was written by Bibek Debroy himself

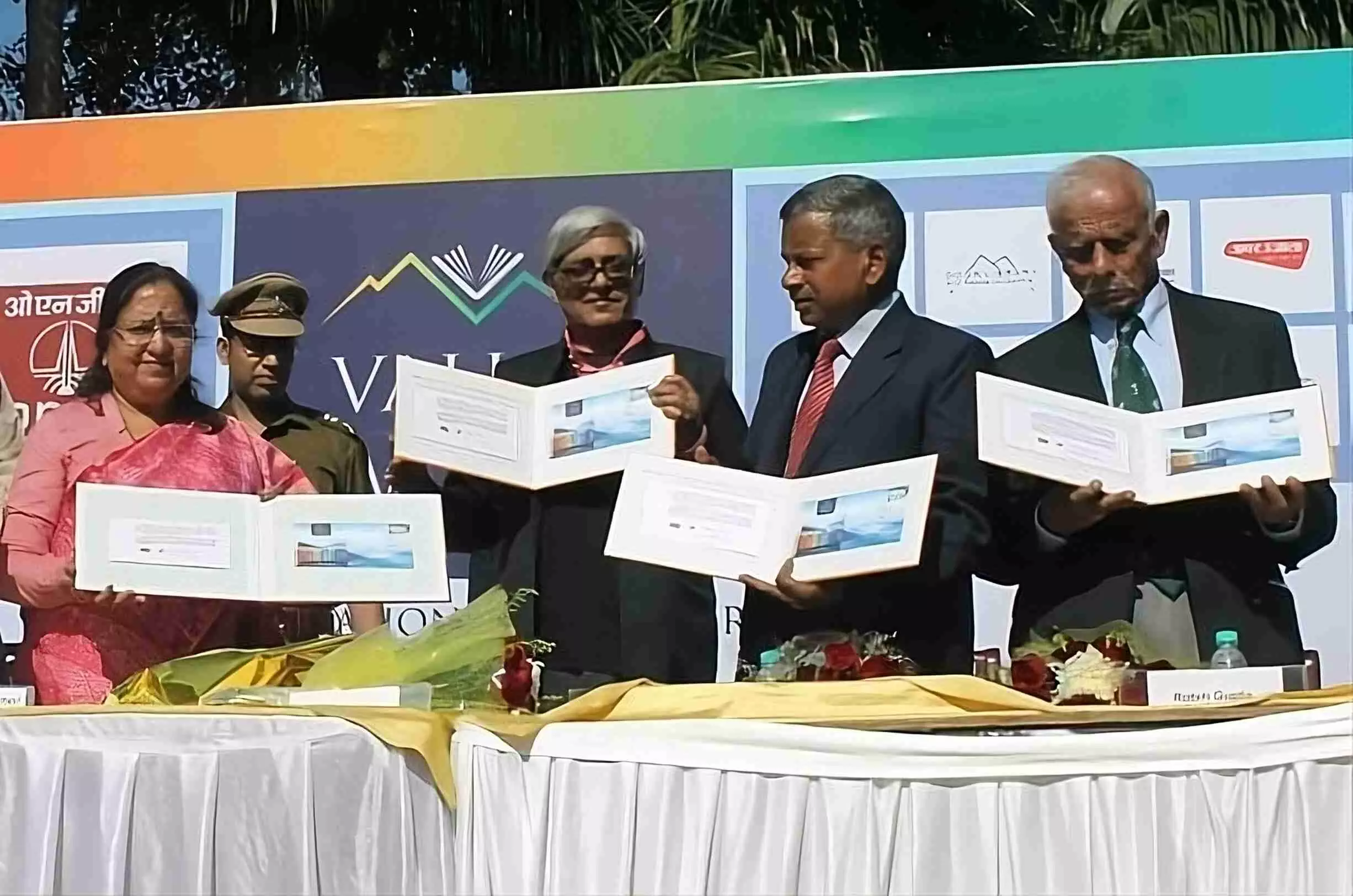

(Left to right) The then Governor of Uttarakhand Ms BR Maurya, Bibek Debroy, CPMG of Uttarakhand and Gen Ian Cardozo

Last month, I sent a WhatsApp message to Bibek Debroy, inviting him to deliver the keynote address at the Chennai edition of VoW on December 13/14. I was a bit concerned, as his reply was not as prompt as usual. A few days later, he wrote back, saying he might not be able to travel outside of Delhi for medical reasons. So, one knew that he was unwell, but the hope and expectation was that he would overcome. Therefore, it was with a great sense of shock that I received the (now viral) forward of his own obituary, which he penned for the Indian Express, where he published his columns regularly. Even as it was reflective of life, death, and the ‘in-between’, it was both realistic and platonic. This was also the first time I had read an online version of an obituary before it appeared in print. Is this a reflection of times to come?

I first met Bibek Debroy professionally when he was at the PHDCCI, and later at the National Commission for Manufacturing Competitiveness. At the time, I was Secretary of Industries in the newly carved-out state of Uttarakhand (then Uttaranchal), and my team at SIDCUL (State Infrastructure and Industrial Development Corporation of Uttarakhand Limited) was in overdrive to attract industry to the state, leveraging the Concessional Industrial Package (CIP), which offered incentives to new units established in hill states. He drew my attention to the fact that, while this strategy was effective in the short term, it was insufficient for the long term. Debroy believed that the only sustainable way to promote industry was by creating an entire ecosystem—not just for manufacturing, but also for research, infrastructure, training, apprenticeships, and educational institutions. What began as conversations on industry often veered toward his translations of the epics, and I was totally mesmerised by his grasp—not only of the Sanskrit shlokas of our epics but also of contemporary issues, whether related to writing instruments, weights and measures, or what he referred to as the terminal decline of educational institutions and industrial establishments in West Bengal.

Our chance meetings in airport lounges and on Kolkata-New Delhi flights (when I was back in my cadre), at a time when he was writing the book on Manmatha Nath Dutt, allowed me to engage with him. He asked if I had come across any references to Dutt in the Asiatic Society or National Library—institutions I frequently visited during my relaxed term as the Director General of the ATI (now Netaji Subhas Bose Administrative Training Institute). It was on one of these flights that I invited him to deliver the keynote address at the second edition of Valley of Words (2018) on ‘Eternal Learnings from Our Scriptures’. This indeed turned out to be one of the most erudite lectures at VoW. In his keynote address, he touched upon the ‘Shanti Parva’ of the ‘Mahabharata’ and the teachings of Ashtavakra. He spoke for a few minutes in Sanskrit: the point he made was that while he was glad that Uttarakhand was the first state in the country to make Sanskrit the ‘second language of the state’, he lamented the fact that not much effort had been made by the successive governments (of both Congress and the BJP) to issue simultaneous gazette notifications in the language. He pointed out that only a fraction of the total corpus available in Sanskrit (as well as Pali and Prakrit) had been retrieved and awaiting translation, while much more remained locked in manuscripts, with a substantial amount lost during the medieval period. He emphasised that for Sanskrit to thrive, people must continue reading and critiquing in it. Latin died because it was no longer in use; Sanskrit still held an advantage as it is used in scripture and prayer (unlike Latin).

I must also mention that our better halves, Rashmi and Suparna Debroy, knew each other well. They would often rag us that one keynote at VoW was not enough. We were looking forward to meeting them both in Chennai, but destiny had other plans. As he wrote in his requiem, like many others, we too will observe a minute’s silence for him at the signature VoW event in Dehradun and at the Chennai edition. Almost every newspaper and magazine will publish his obituaries and reprint some of his seminal texts, but how long will this remembrance last? All I can say is that, unlike monuments, manuscripts and texts have a longer shelf life, and whenever there is a discussion on the resurrection of Sanskrit texts, he will be remembered.

Before closing, here is an appeal—perhaps his last wish of being awarded a Padma Vibhushan, albeit posthumously, might be granted by the government. This would indeed be a fitting tribute to a towering public intellectual of our times.

The writer, a former Director of LBS National Academy of Administration, is currently a historian, policy analyst and columnist, and serves as the Festival Director of Valley of Words — a festival of arts and literature