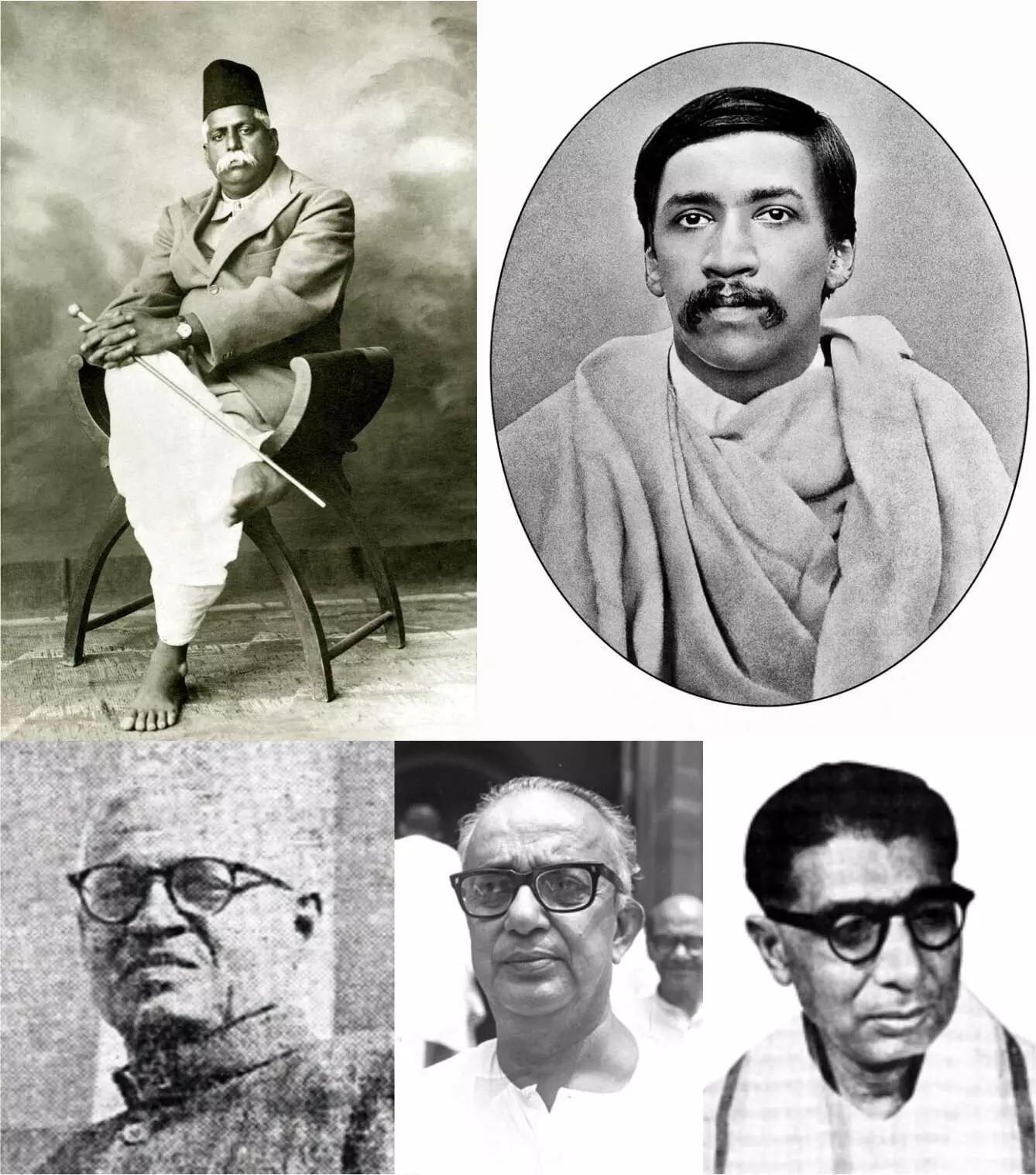

A Soldier of the Anushilan Samiti

As a young medical student in Kolkata, Hedgewar was deeply involved with the revolutionary Anushilan Samiti—which was influenced by Bengal’s Swadeshi movement—and later channelled his nationalist fervour into founding the RSS

Dr Hedgewar had a close association with and was an active member of the Anushilan Samiti as a student in Kolkata. Like Sri Guruji later, Dr Hedgewar also spent some of his formative and most impressionable years in Bengal, then in the throes of the Swadeshi movement. He spoke fluent Bengali and was well versed with the spirit and psyche of Bengal. Even while in Nagpur as a student Dr Hedgewar had been associated with groups which were active in mobilising funds for the famous Alipore Bomb Case which had Sri Aurobindo, Barindra Kumar Ghose, Upendranath Banerjee and Ullaskar Dutt, among other revolutionaries, as the principal accused.

The Alipore Bomb Case was the first such trial with a national impact and magnitude. In his authoritative 1922 study of the Alipore Bomb Trial, Bejoy Krishna Bose observes that the Alipore Bomb Trial, “was the first state Trial of any magnitude in India, because it was held at a time when discontent reached its highest point in Bengal and it concerned people who were gentlemen belonging to the best society, cultured, educated and highly intelligent.” Referring to the plethora of evidence presented in the court for this historic trial, Bose pointed out that even ten volumes would not “afford sufficient space for a complete history of the trial.”

Doctorji’s association as a member of the Anushilan Samiti while studying medicine at the National Medical College in Kolkata had brought him in close contact with a number of leading revolutionaries of that era. His involvement with the Anushilan Samiti as a member of its inner circle is well documented. Those who minimise Doctorji’s involvement with the freedom movement belong to an ideological class and ecosystem whose members were collaborationists and have had a history of opposing the freedom struggle. The history of the Anushilan Samiti is in itself a thrilling account of how some of India’s most dedicated and battle-hardened revolutionaries carried on a relentless fight against colonial rule and bondage.

Of Pramatha Nath Mitra, better known in the annals of Indian revolution as P. Mitra, the founder of the Anushilan Samiti, historian Niharranjan Ray (1903-1981), writes, in a study of the movement, ‘Freedom Struggle and Anushilan Samiti’, that back in India from England, Mitra was “disappointed and distressed by the ineffectual policy and programme of the then Congress, not very much unlike what Aurobindo was, [and] he came to believe that the way to India’s freedom from the bondage of the British yoke, was to build up, slowly and steadily, a band of young men healthy and strong in body and mind, fearless and dedicated, disciplined as soldiers…He believed that the band of young men of his imagination and design, pledged to secrecy but increasing in numerical strength in an ever-widening circle would one day be India’s army of liberation which would strike when the time was ripe.” Ray was himself involved with the Anushilan Samiti’s mission as a college student in Mymensingh district of East Bengal, his account, therefore, bears greater credibility than many other readings of the Samiti. Sri Aurobindo offers an interesting insight into P. Mitra’s personality. He had “a spiritual life and aspiration of his own and a strong religious feeling; he was like Bepin Pal and several other prominent leaders of the new national movement in Bengal, a disciple of the famous Yogi Bejoy Goswami…” A towering Vaishnava saint and reformer of his era Bijoy Krishna Goswami (1841-1899) had a far-reaching impact on a number of leading minds of his era and later. Of P. Mitra’s work, Sri Aurobindo writes, “The work under P. Mitra spread enormously and finally contained tens of thousands of young men and the spirit of revolution spread by Barin’s [Barindra Kumar Ghose] paper Yugantar became general in the young generation.”

Tridib Chaudhuri (1911-1997), veteran freedom fighter and parliamentarian, once an active member of the Anushilan Samiti and a repository of the movement’s history and evolution argues in his introduction to the ‘Freedom Struggle and Anushilan Samiti’ that the Anushilan Samiti founded in Kolkata around 1902 as a “revolutionary cultural and youth organisation” always “played a pivotal and central role in the growth and development of the anti-imperialist national revolutionary movement” in India “from the early days following the martyrdom of Chapekar Brothers and Rand murder at the turn of the 19th century to the days of Azad Hind Fauz’s struggle against the British rulers on Kohima front in 1944.” He draws a long line of revolutionary movements and associations which can be traced back to the Samiti.

The formation of the Anushilan Samiti, Chaudhuri tells us, “Came five years after the killing of Rand and Ayerst in Poona in 1897 by the Chapekar Brothers and three years before the partition of Bengal in 1905, which started the first popular wave of intense patriotism and anti-British political agitation in the country. By any criterion it was a climacteric juncture in the national history of modern India which broke the barriers that held back the onrush of revolutionary currents in the battle of national freedom…”

The Samiti’s activities thus must have begun to be known in the Maharashtra region, attracting young minds in whom the seeds of freedom were sown following the actions of the Chapekar Brothers which had a deep impact across the province. The actions of the Chapekar Brothers, as we know, was not an isolated event. The contributions of the iconic Vasudev Balwant Phadke in the late 1870s had sown the seeds of revolt.

Legendary historian R.C. Majumdar notes in his monumental ‘History of the Freedom Movement in India’, that Phadke’s action “left its legacy, and the seeds he sowed grew into a mighty banyan tree with its roots spread over India, in about a quarter of a century. His daring spirit was taken up by the Chapekar brothers in Maharashtra, and from them it was taken over by the revolutionaries in Bengal and other parts of India. His methods of secretly collecting arms, imparting military training to youths and securing necessary funds by means of political dacoities were adopted by the latter.” Phadke, Majumdar argues, can “be justly called the father of militant nationalism in India.” It is not unlikely thus that the Anushilan Samiti and its founding leaders were inspired by Phadke and the Chapekar Brothers in their methods and preparation for revolution. An early and authentic biography of Sri Aurobindo, by A.B. Purani, mention’s Sri Aurobindo’s reference to the existence of a powerful secret society in Maharashtra “presided over by Thakur Ramsingh, a Rajput prince” with its “Bombay branch” being “managed by a council of five. Sri Aurobindo was able to contact this body and joined it.” By then he had already initiated his activities in Bengal. Many of those who teamed up with Sri Aurobindo in Bengal belonged to the Anushilan Samiti.

The young Dr Hedgewar, thus, having grown up in such a milieu in end of the century Maharashtra, was also one of those who was sucked into the vortex of the Anushilan Samiti’s activities. He became intrinsically tied with this robust and rooted revolutionary movement.

Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee (1895-1960), freedom fighter, parliamentarian and an active member of the Anushilan Samiti, in his voluminous memoirs of the freedom struggle and of his days with the Anushilan Samiti, ‘In Search of Freedom’ (1967) refers to Doctorji’s association with the Samiti. “Dr Hedgewar of Nagpur”, writes Chatterjee, “became a member of the Samiti when he was a student of the National Medical College in Calcutta. He led a life of mission and later started the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangha…”

The writer is a member of the National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Chairman of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal