Wide-ranging contestations

Nizam’s Firmans represented just one aspect; a whole lot of diverse factors including language, religion, ideology and quest for power were shaping the larger political picture of Hyderabad

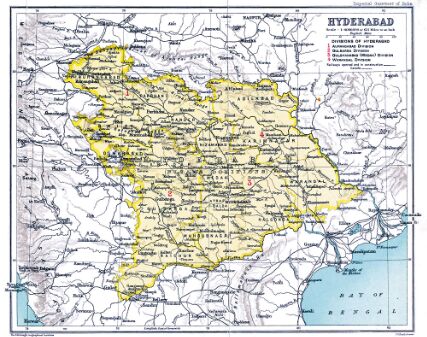

Lest one gathers the impression that Hyderabad was all about the Nizam and his Firmans, it must be placed on record that the nationalist, linguistic, ethnic and communal ferments brewing in the rest of the country were impacting this princely state as well. Mahatma Gandhi had returned from South Africa in 1915 and, starting with the Champaran Satyagraha in 1917, he transformed the Congress from a debating society to a mass movement, which would take up issues affecting the daily lives of people – from the Champaran Satyagraha to support for Khilafat. Satyagraha emerged as a popular 'weapon of the weak against the mighty state'. The Congress decided in 1921 that its own internal organisation would then be based on the 'linguistic principle'— subsequently, the Sindh, Maratha, Gujarati, Oriya and Kannada circles were formed. The pride in one's own language became a badge of honour. It was in this context that the refusal to allow a resolution in Telugu at Nizam's Social Reforms Conference in Hyderabad in November 1921 led to the formation of Andhra Jana Sangham with twelve members. It, however, organised its first conference with over a hundred delegates in February 1922 with KVR Reddy as the chairman and Hanumantha Rao as the secretary. Within two years, 50 branches had been established in the Telangana region. It also started having regular conferences but, in 1930, it morphed into the Andhra Mahasabha. The focus now shifted towards economic and social reforms, abolition of untouchability and security of tenure. However, in the subsequent decade, ideological differences within the Andhra Mahasabha led to one faction merging with the Congress and the other with the Communist party of India.

On one hand, if the Andhra Mahasabha was focused on Telugu language and social reform, the Arya Samaj movement, on the other hand, took on the 'Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen' and its attempts towards 'proselytisation', allegedly with implicit support from the Nizam. The Arya Samaj pointed to Mafusa and Gayar Mafusa — the two Firmans issued in the Fasli year 1339 (corresponding to 1929). These related to 'protection against the eviction of Muslim landowners' and 'permission to Muslims to take over the mortgaged lands of the Hindus'.

Founded in Gujarat by Dayanand Saraswati, the Arya Samaj was most active and influential in Punjab and Hyderabad – regions where the Hindus were in a minority and were supposedly facing the intellectual, scriptural and cultural onslaught of the Muslims, including conversions among the peasantry and artisan classes. Before the establishment of the Samaj, there was hardly any resistance against conversion and, once converted, there was no way of getting re-acceptance into the Hindu fold. Swami Dayanand Saraswati, however, introduced the concept of shuddhi – purification for returning to the fold of Hinduism.

Arya Samaj had major ideological differences with the Hindu Mahasabha which followed the Sanatana Dharma. Unlike the Arya Samaj, the Hindu Mahasabha was not as vigorously opposed to the caste system. But, when it came to opposing proselytisation, they came together. Of course, the Arya Samaj had the upper edge, for it actively sought out recent converts, and got them back to the larger Hindi pantheon. The Arya Samaj received a fillip with the election of Chief Justice Pandit Keshav Rao Koratkar as the President of Hyderabad Arya Samaj in 1905. Over the next three decades, the Arya Samaj had 250 branches in the state, 20 of which were located in the twin cities of Hyderabad and Secunderabad.

The elections held under the GoI Act, 1935 (albeit on a limited mandate) saw Congress emerging as the ruling party in all the three provinces surrounding Hyderabad. In February 1938, the Indian National Congress passed the Haripura resolution declaring that the princely states were "an integral part of India", and that it stood for "the same political, social and economic freedom in the states as in the rest of India". This announcement spurred the formation of the Hyderabad State Congress, and an enthusiastic drive to enrol the members began. By July 1938, the committee claimed to have enrolled 1200 primary members and called upon both Hindus and Muslims of the state to "shed mutual distrust" and join the "cause for responsible government under the aegis of the Asaf Jahi dynasty." Despite their protestations of loyalty, the Nizam felt threatened and promulgated a new Public Safety Act in 1938. He also declared the Hyderabad State Congress illegal. Meanwhile, the communal situation remained tense and, hoping to capitalise on the communal tensions that had been on the boil since early 1938, the Arya Samaj announced a Satyagraha on October 24, 1938. Perhaps in the bid to avoid being outdone, the activists of the Hyderabad State Congress formed a 'Committee of Action' and also announced their satyagraha on the same day. In effect, it became a common call against the Nizam by all the three organisations — the Arya Samaj, the Hindu Mahasabha and the Congress. But the Congress high command did not appreciate this local arrangement and relied on the report of Padmaja Naidu in which she castigated the State Congress for lacking unity and cohesion and also for being 'communal'. On December 24, the State Congress suspended the agitation after 300 activists had courted arrest, but the Arya Samaj and the Mahasabha continued their agitation well into the 1940s. The leaders of the Hyderabad Congress did launch a nonviolent campaign of civil disobedience — a satyagraha for civil rights and representative democracy — alongside supporting the Quit India movement led by the Indian National Congress in 1942. But the political mobilisation among the Hindus in the state centred around the Arya Samaj and the Andhra Mahasabha.

However, it would not be correct to portray this struggle in the context of the Hindu-Muslim binary alone as there were many other contestations – within Hindus, among the Telugu, Kananga and Maratha speakers, as well as between the Brahmins and the rest. Contestations were also between the Arya Samaj, the Hindu Mahasabha and the Congress. The Muslims too were divided between the Mulkis and the non-Mulkis, and the Rizvi and anti-Rizvi factions. With the announcement of the Indian Independence Act, the Congress and the Arya Samaj started the 'Join Indian Union' movement which was, of course, resisted by the Ittehad and the Razakars. The Nizam's writ no longer ran beyond Hyderabad city and the surrounding villages. The stage was set for Operation Polo to which a reference was made in the previous column.

Views expressed are personal