An improbable merger

Recounting the circumstances behind the 1956 proposal to merge Bihar and West Bengal as a way of settling interstate border disputes

Before we take up the discussion on the formation of Jharkhand, along with Chhattisgarh and Uttarakhand in 2000, it is important to also reflect on a proposal in 1956 to merge Bihar and West Bengal, a move which came around the time of the SRC recommendations. This was indeed a very novel attempt to settle inter-state border disputes by creating a supra entity, but though it had the support of both the chief ministers' BC Roy (West Bengal) and Shrikrishna Sinha (Bihar) as well as the Union Cabinet, it was opposed tooth and nail by the Communists as well as the Praja Socialist Party, and even though both the Bihar and West Bengal assemblies had resolved in favour of the merger, in view of the intense agitation in Kolkata, and the defeat of Congress in nine municipalities (including Barrackpore) and the resounding defeat of the pro merger Congress candidate Ashok Sen in the prestigious North-West Calcutta Parliamentary Constituency by the Left-supported West Bengal Linguistic States Redistribution Committee (LSRC) Mohit Moitra. The editorial comment on the Economic Weekly (precursor to EPW) said 'Apart from yielding an ideological dividend in reversing the trend towards linguistic destruction of the nation, the proposal for the merger of Bengal and Bihar hailed so recently as constituting a new dawn of hope does not seem at first sight to have any particularly attractive features and has been so assessed by the general public, at least in Bengal'.

What led BC Roy (the more influential, better-known leader) to propose the merger which would have made Bengalis a minority in the new state? For Roy, one of the main considerations was the rehabilitation of the growing stream of refugees from East Bengal. Roy looked at the reallocation of frontiers of his state 'mainly for solving the linguistic and administrative problems as well as to reallocate the refugees from East Pakistan'. He was most impressed by the manner in which the state of Punjab had been able to rehabilitate Punjabis from across the border on the abundant lands in Kurukshetra, Faridbabdm Sonepat, Panipat and Urgain, as well as the allocation of abundant land in the districts of Karnal and Kurukshetra. On the other hand, refugees from East Bengal were sent to places like Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and UP where they did not have a 'political voice', and felt absolutely abandoned. It was also felt that major river basin development projects like DVC (for irrigation, flood control and power) covered both the states, and it would make financial and administrative arrangements better. Calcutta had the capital and Bihar had the mineral resources: and this too could have led to the rapid industrialisation of the new state!

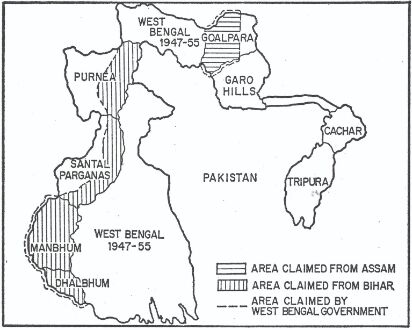

Incidentally, the representations made to the SRC did not include the Roy Sinha proposal. The four memoranda put up before the SRC were based on different sets of factors, each demanding some area from the neighbouring state. The State PCC memorandum sought an additional area of 21,352 square miles and a population of 8.2 million from the states of Bihar, Orissa and Assam. The state government proposition was far more realistic and sought the transfer of four districts of Bihar (Purnea, Santhal Parganas, Manbhum and Dalbhum) besides Goalpara from Assam. The third proposal came from the Left dominated LSRC, which claimed all of the territory contiguous to WB in which Bengali speaking people dominated — a position midway between the state government and the West Bengal PCC. The Jana Sangha came out with yet another formula: the states of Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, Assam be combined with the centrally administered states of Manipur and Tripura to form one state, to be called Purbanchal Pradesh (Eastern Region).

It must be mentioned that while the editorial and the letters to the editor across few prominent English newspapers were supportive of organising India on administrative convenience, the Hindi and regional language papers were supportive of the reorganisation on linguistic lines.

The matter came up before the Calcutta High Court as well, in which West Bengal Legislator, Hem Chandra Sengupta, argued that as the legislative Assembly of Bengal had taken the decision of Western districts joining India and Eastern districts joining Pakistan, the territorial integrity of the state could not be compromised. He also described himself as a citizen of West Bengal. Dismissing his appeal, the Court held that both the Constitution of India and the Indian Citizenship Act only recognised an Indian citizen, and though states were a constituent part of India, they had no independent, or sovereign existence. The High Court also held the view that there was no distinction between Part A and Part B states concerning the alteration of boundaries, and that the Union Parliament was competent to do so, and that while the President may consult the state governments, the views of the state government were not binding on him.

While the merger did not happen, territorial adjustments did take place, about which we shall discuss next Sunday.

The writer is the Director of LBSNAA and Honorary Curator, Valley of Words: Literature and Arts Festival, Dehradun

Views expressed are personal