Economics of asymmetric information

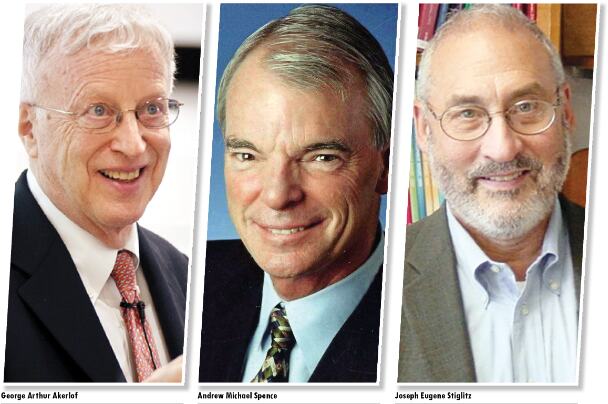

George Akerlof, Michael Spence and Joseph Stiglitz applied the concept of information asymmetry to wide-ranging areas, enabling a more real-world approach than in assumed symmetric set-up of neoclassical framework

The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001 was awarded jointly to George A Akerlof of University of California in Berkeley, Michael Spence of Stanford University and Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University, "for their analysis of markets with asymmetric information".

Akerlof finished his BA from Yale University in 1962 and went on to complete his PhD in economics from MIT in 1966. In 1966, he began teaching at the University of California and retired as professor emeritus in 2010. Akerlof also taught at various other institutions, including the London School of Economics and Georgetown University. His main work was on the economics of asymmetric information, which was largely inter-disciplinary, drawing from subjects such as psychology, anthropology, and sociology.

Spence is currently a professor at the Stern School of Business at New York University, and also at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He received his middle and high school education at the University of Toronto. He later went to Princeton for his undergraduate studies in philosophy, which he completed in 1966. Spence then studied at Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar and received a BA/MA degree in mathematics in 1968. Spence received a PhD in economics in 1972 from Harvard University, completing a dissertation titled 'Market signalling' under the supervision of Kenneth Arrow and Thomas C Schelling.

Stiglitz attended Amherst College for his undergraduate studies. In 1965, he moved to the University of Chicago to do research. He studied for his PhD from MIT from 1966 to 1967, during which time he also held an MIT assistant professorship. From 1966 to 1970, he was a research fellow at the University of Cambridge. In subsequent years, he held academic positions at Yale, Stanford, Oxford and Princeton. Since 2001, Stiglitz has been a professor at Columbia University, with appointments at the Business School, the Department of Economics and the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA).

In this article, we will look at the main works of Akerlof, Spence and Stiglitz.

Main works of George Akerlof

Akerlof's work on asymmetric information in the used car market is perhaps his best-known work. His article 'The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism', published in the 'Quarterly Journal of Economics' in 1970, has become standard reading in microeconomics courses, the world over. Akerlof's point was simple: There is an asymmetry of information between the buyers and sellers of used cars (called lemons), which leads to a collapse of the market. While the seller knows the true value of the car, the buyer doesn't. The buyer is therefore willing to pay an average price, which is between the price of a premium car and a lemon. In such a situation, sellers would only prefer to hold lemons and sell them, since that alone would be profitable. This will lead all the premium cars to leave the market and only lemons will be left behind, further resulting in fall in price of the cars as word gets around. Thus, the uninformed buyer's price creates an adverse selection problem that drives out the high-quality cars from the market. Akerlof suggested that strong warranties were one way to overcome the lemons problem. Akerlof's work has been applied in various sectors ranging from the labour market to the insurance sector.

Akerlof has also written a number of books, some of which are: 'Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism' (2009) and 'Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception' (2016). Both the books were written with Robert J Shiller.

Main works of Michael Spence

Like Akerlof, Spence worked on the economics of asymmetric information. More specifically, he developed the theory of market signalling in the labour market under conditions of asymmetric information. His seminal paper in 1973, titled 'Job Market Signalling' argued that education was a good signalling mechanism in the job market and a college degree indicated the job seeker's ability to perform. Other examples of signalling included corporations giving large dividends to demonstrate profitability and manufacturers issuing guarantees to convey the high quality of a product.

Elaborating on the theory of market signalling in the job market, Spence suggested that better candidates had a greater incentive to communicate their qualities and abilities. For this, they were willing to incur costs such as obtaining a college degree. Spence looked at hiring as an investment decision under uncertainty. A job seeker's attributes that are observable (such as age and gender) are called indices, and those that are unobservable are termed 'signals'. While the job seeker can't tinker around with indices, he can manipulate the 'signals'. The employer assesses these 'signals' based on past experiences and assigns probabilities to different types of signals. These assessments are continuously updated based on the signals. This is called the feedback loop. Spence studied the signalling equilibrium that may result from such a situation. It is important to note that the signal has value to the job candidate, independent of any increase in skill or knowledge obtained in the course of their studies; they might not even gain any new skills, knowledge, or other increase in ability from their education.

While job market signalling is his best-known work, Spence also worked on development economics and documented the success of the export-led strategy which was followed by several countries. Spence also worked on issues related to monopolistic competition and industrial organization. His models demonstrate how monopolistic competition can lead to distortion of markets and misallocation of resources (relative to perfect competition) which, he argues, might be remedied through various forms of regulation.

Main works of Joseph Stiglitz

Stiglitz also contributed to the economics of asymmetric information. His most well-known work in this area is on screening. According to Stiglitz, screening is a technique used to extract information. More specifically, screening is used by those poorly informed to extract information from the better informed. An example is the screening done by insurance companies to separate high-risk subscribers from low-risk ones so as to charge premiums appropriately. As the Nobel website tells us:

Joseph Stiglitz clarified the opposite type of market adjustment, where poorly informed agents extract information from the better informed, such as the screening performed by insurance companies, dividing customers into risk classes by offering a menu of contracts where higher deductibles can be exchanged for significantly lower premiums. In a number of contributions about different markets, Stiglitz has shown that asymmetric information can provide the key to understanding many observed market phenomena, including unemployment and credit rationing.

Stiglitz also worked on issues arising out of incomplete information, where even perfectly competitive markets can't achieve social efficiency. In a paper co-authored with Andrew Weiss, he showed that credit will be rationed below the optimal level, if banks used interest rates to separate borrowers' types. Stiglitz also showed that a competitive market may not lead to a full insurance coverage of the people since some firms may offer cheaper insurance to those with a lower risk.

In addition to his work on economics of asymmetric information, Stiglitz also worked in the areas of public finance, monopolistic competition, and labour economics. In public finance, Stiglitz proposed that land rents could fund the supply of public goods. He called this the Henry George Theorem after the economist Henry George who had advocated a land value tax. In monopolistic competition, the Dixit-Stiglitz model is well known. In this model, they showed that in presence of increasing returns to scale, very few firms enter the market. The model was extended by taking into account the consumers' preference for diversity, and here, a greater number of firms entered the market. The model was extended to include international trade by Paul Krugman.

In labour economics, the Shapiro-Stiglitz efficiency wage model is well known. The model was proposed by Shapiro and Stiglitz in 1984 in a paper titled: 'Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Discipline Device' in 'The American Economic Review'. According to this model, workers get those wages that prevents shirking, preventing the wages from falling to fall so as to clear the labour markets. In other words, wages are sticky downwards. The model sought to explain the reasons for involuntary unemployment.

Stiglitz was also active in public life and held important positions in various Administrations as well as international organizations and foreign governments. He was a member of the Council of Economic Advisors from 1993-95, during the Clinton administration, and served as CEA chairman from 1995-97. He then became Chief Economist and Senior Vice-President of the World Bank from 1997-2000. In 2008, he was asked by the French President Nicolas Sarkozy to chair the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, which released its final report in September 2009. In the same year, he was appointed by the President of the United Nations General Assembly as chairman of the Commission of Experts on Reform of the International Financial and Monetary System, which also released its report in September 2009 (published as 'The Stiglitz Report'). Since the 2008 crisis, he has played an important role in the creation of the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET).

Stiglitz is also a prolific author and has written profusely on topics such as globalization, its effects, and how to manage them. His books include 'Globalization and Its Discontents' (2002), 'Fair Trade for All' (2005, with Andrew Charlton) and 'Making Globalization Work' (2006). In 'The Roaring Nineties' (2003), he explained how financial market deregulation and other actions of the 1990s were sowing the seeds of the next crisis. Concurrently, in 'Towards a New Paradigm in Monetary Economics' (2003, with Bruce Greenwald) he explained the fallacies of current monetary policies, identified the risk of excessive financial interdependence, and highlighted the central role of credit availability. There are numerous other books to his credit on a variety of topics ranging from the Great Recession, Iraq conflict and the American economy.

Conclusion

Akerlof, Spence and Stiglitz made fundamental contributions in the economics of asymmetric information. Their work relaxed the assumption of complete and symmetric information of the neoclassical model and thereby sought to bring microeconomics closer to decision making in the real world. Their work introduced us to the concepts of adverse selection and moral hazard, both of which arise out of asymmetric information. As we know, adverse selection arises when either buyers or sellers have more information about the product than the other. For example, the market for lemons introduced by Akerlof. Moral hazard, on the other hand, arises after the agreement between the parties, when one party provides misleading information or changes his behaviour. For example: A person indulges in behaviour risky to his health after buying a health insurance policy such as increasing smoking. Not surprisingly, the work of the three Nobel laureates is still widely applied in various areas ranging from Insurance, to Corporate Finance to wage contracts.

The writer is an IAS officer, working as Principal Resident Commissioner, Government of West Bengal. Views expressed are personal